Few bands seem to cause such division as Simple Minds. There are fans of the early stuff, fans of the later stuff, fans of New Gold Dream…. I never had a horse in that race, since I never particularly cared to follow them. I liked what I heard on the radio of theirs well enough, it was certainly expertly crafted and, in retrospect, helped define its time. But recently I felt like mining a bit deeper and came upon their early records. I understand the early fans’ passions more now, since it’s made clear on Real to Real Cacophony and Empires and Dance that the band was chasing an ambition to recast pop music coming out of the 70s. That they caught up with it is apparently a deep disappointment for those who read sellout in the tracks of Once Upon a Time, but of course the one — a deeply enjoyable confection of well-honed hooks and musicianly smarts, no matter its commerciality — would not have been possible without the other, a proving ground that was hit and miss, but when it found its mark was incendiary.

Few bands seem to cause such division as Simple Minds. There are fans of the early stuff, fans of the later stuff, fans of New Gold Dream…. I never had a horse in that race, since I never particularly cared to follow them. I liked what I heard on the radio of theirs well enough, it was certainly expertly crafted and, in retrospect, helped define its time. But recently I felt like mining a bit deeper and came upon their early records. I understand the early fans’ passions more now, since it’s made clear on Real to Real Cacophony and Empires and Dance that the band was chasing an ambition to recast pop music coming out of the 70s. That they caught up with it is apparently a deep disappointment for those who read sellout in the tracks of Once Upon a Time, but of course the one — a deeply enjoyable confection of well-honed hooks and musicianly smarts, no matter its commerciality — would not have been possible without the other, a proving ground that was hit and miss, but when it found its mark was incendiary.

“Premonition” has at its center a chunky classic rock riff driven by Charlie Burchill’s guitar, and isn’t too distant from what the Cars and Tubeway Army were doing at a time before the keyboards really took complete hold, combining the ethic of early Roxy Music with a post-punk focus on rhythm (Derek Forbes and Brian McGee brought genius to this band). Jim Kerr sings with a wide-eyed weirdness straight out of Marquee Moon, while Mick MacNeil’s carnivalesque keyboarding from this time must have influenced fellow Glaswegians Belle & Sebastian (thinking specifically of “Lazy Line Painter Jane”).

This live rendition — though honestly the sync seems odd enough to me and the recording good enough that there may be some yet-to-be-defined disconnect between picture and sound — catches Simple Minds in their early prime (and goes some way to explaining why they were offered a certain song to sing for a certain movie after Bryan Ferry turned it down). They were catching fire creatively, figuring it out and putting it out live. That their trajectory afterwards went on to follow that of Ferry et al. is perhaps the sign of one common path in a larger creative process tied to myriad motivations. Me? If I had to decide which Simple Minds I prefer…I’d take both.

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section above.

The principles of exclusion, constraint, and limitation are drivers of art as much as what ends up on the canvas, and more than anything explain how U2’s “The Three Sunrises” did not make the cut of their seminal 1984 album The Unforgettable Fire. That album, their fourth, changed the band’s trajectory by broadening their palette (thus ultimately guaranteeing their longevity). Subduing the band’s onward-Christian-soldier martial airs without dulling its passion, producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois — who the previous year had created, along with Roger Eno, one of the great ambient masterworks in Apollo — worked at applying creative filters to make a music that was moody, introspective, less deliberate but also more whole. The Unforgettable Fire feels more like an album with a sonic narrative than any of its predecessors. Still, no one, not even Eno, could contain U2’s spirit or strong self-identity, and the recording sessions yielded some work with one foot still grounded in the energetic brightness characterizing their previous catalog.

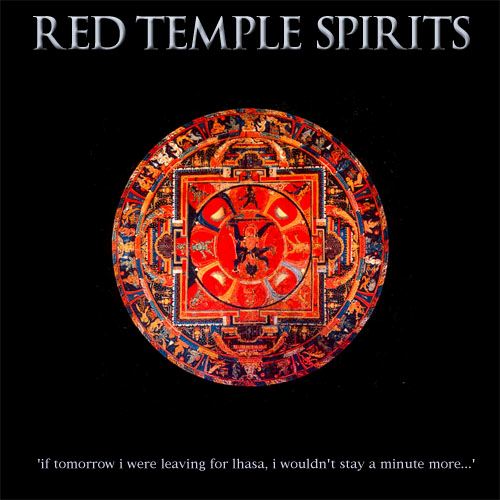

The principles of exclusion, constraint, and limitation are drivers of art as much as what ends up on the canvas, and more than anything explain how U2’s “The Three Sunrises” did not make the cut of their seminal 1984 album The Unforgettable Fire. That album, their fourth, changed the band’s trajectory by broadening their palette (thus ultimately guaranteeing their longevity). Subduing the band’s onward-Christian-soldier martial airs without dulling its passion, producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois — who the previous year had created, along with Roger Eno, one of the great ambient masterworks in Apollo — worked at applying creative filters to make a music that was moody, introspective, less deliberate but also more whole. The Unforgettable Fire feels more like an album with a sonic narrative than any of its predecessors. Still, no one, not even Eno, could contain U2’s spirit or strong self-identity, and the recording sessions yielded some work with one foot still grounded in the energetic brightness characterizing their previous catalog. For years, LA’s Red Temple Spirits were a tease, a psych rock ghost that once got a short write-up in Rolling Stone, which gave an address to write to if you wanted the album, an address for an obscure label that never wrote back. It was the pre-internet treasure map to sacred recordings process that was our siren’s call. Guesswork, album reviews, dudes in record stores who’d gone to see Hendrix and never really come back. From the description I read, this band was for me. But for about five years, every record store I walked into got the question: “Red Temple Spirits?” and I would receive a shake of the head back. Along with Television Personalities, in the late 80s and early 90s they were my grail, a band whose records couldn’t seem to be found for love or money, as if they wanted it that way, ached to be left alone. Around 1993 I finally and gratefully scored a cassette of their 1989 album If tomorrow I were leaving for Lhasa I wouldn’t stay a minute more… (possibly from Austin’s Waterloo records, who had hooked me up with Television Personalities a couple years earlier too) and discovered the small window of hype Rolling Stone gave them was deserved. A rockier, psychier version of the

For years, LA’s Red Temple Spirits were a tease, a psych rock ghost that once got a short write-up in Rolling Stone, which gave an address to write to if you wanted the album, an address for an obscure label that never wrote back. It was the pre-internet treasure map to sacred recordings process that was our siren’s call. Guesswork, album reviews, dudes in record stores who’d gone to see Hendrix and never really come back. From the description I read, this band was for me. But for about five years, every record store I walked into got the question: “Red Temple Spirits?” and I would receive a shake of the head back. Along with Television Personalities, in the late 80s and early 90s they were my grail, a band whose records couldn’t seem to be found for love or money, as if they wanted it that way, ached to be left alone. Around 1993 I finally and gratefully scored a cassette of their 1989 album If tomorrow I were leaving for Lhasa I wouldn’t stay a minute more… (possibly from Austin’s Waterloo records, who had hooked me up with Television Personalities a couple years earlier too) and discovered the small window of hype Rolling Stone gave them was deserved. A rockier, psychier version of the  The Cure’s Disintegration is a lush, beautiful masterpiece. When it was released in 1989, the band was cresting a wave of popularity, and rare was the college dorm room in America that didn’t have a copy of their singles comp, Staring at the Sea (1986), sitting next to the deck, while Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me (1987) was radio ready. Robert Smith had become an unlikely hero, a post-punk goth who had paid his dues and, with a colossal songwriting talent, was reaping the rewards of someone who virtually created his own genre. Nobody else sounded like the Cure. Neither psychedelic nor prog nor punk, but fearless in their approach, comfortable in their painted skin. On Disintegration the band slows the tempos, backgrounding Smith’s economical lyrics with huge keyboard/guitar drift pieces that seem to exist in the gloaming. A perpetually wilting flower, the first-person character in Smith’s work has had a long shelf life, and would rot if it weren’t for Smith’s genius with song and his ability to effortlessly write pop hits at will. Entreat is from the tour supporting the album, recorded at Wembley in ’89, and consists of the all the songs on Disintegration in the same running order. It had a very limited release originally, but pieces of it emerged here and there on CD singles taken from Disintegration (I first heard parts of it on the Pictures of You EP), and was eventually, finally bundled with Disintegration on the 2010 re-release. Entreat was a bold move, a full performance of a newly-released record, and demonstrates just how confident Smith and his band were in the new songs.

The Cure’s Disintegration is a lush, beautiful masterpiece. When it was released in 1989, the band was cresting a wave of popularity, and rare was the college dorm room in America that didn’t have a copy of their singles comp, Staring at the Sea (1986), sitting next to the deck, while Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me (1987) was radio ready. Robert Smith had become an unlikely hero, a post-punk goth who had paid his dues and, with a colossal songwriting talent, was reaping the rewards of someone who virtually created his own genre. Nobody else sounded like the Cure. Neither psychedelic nor prog nor punk, but fearless in their approach, comfortable in their painted skin. On Disintegration the band slows the tempos, backgrounding Smith’s economical lyrics with huge keyboard/guitar drift pieces that seem to exist in the gloaming. A perpetually wilting flower, the first-person character in Smith’s work has had a long shelf life, and would rot if it weren’t for Smith’s genius with song and his ability to effortlessly write pop hits at will. Entreat is from the tour supporting the album, recorded at Wembley in ’89, and consists of the all the songs on Disintegration in the same running order. It had a very limited release originally, but pieces of it emerged here and there on CD singles taken from Disintegration (I first heard parts of it on the Pictures of You EP), and was eventually, finally bundled with Disintegration on the 2010 re-release. Entreat was a bold move, a full performance of a newly-released record, and demonstrates just how confident Smith and his band were in the new songs.