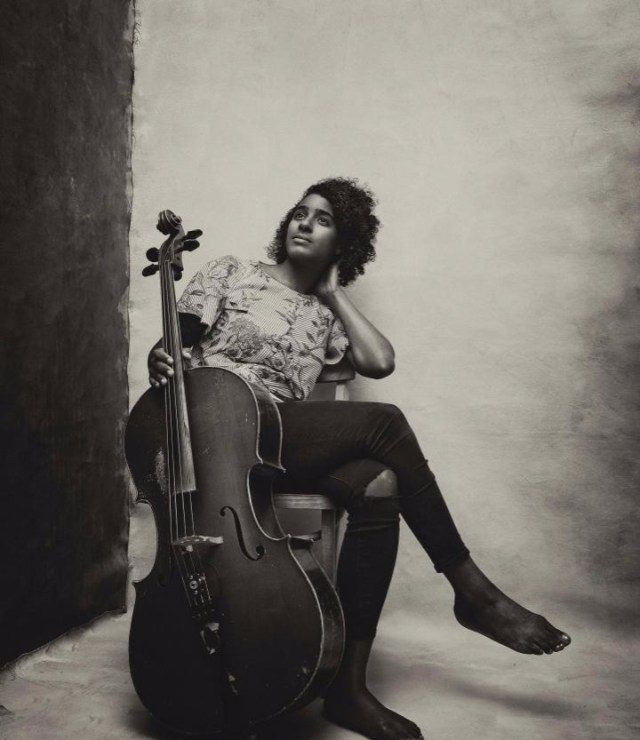

Free and blue and beautiful, those moorings Leyla McCalla holds to in her music sway and pitch like the gulf waters from Hispaniola to Lousiana, rolling through her cello and voice and coursing through her songs, lifeblood to an American music heart. In the weaving lines of the music she plays — a snaking, sliding creole so suited to, and perhaps partly a consequence of, the playing of fretless instruments — is the sound of an America taking shape as its many diasporas meet and mix and move, intersecting lines on a map that triangulate on New Orleans. Like the best Americana musicians, McCalla achieves something at once utterly contemporary but steeped in an authenticity of sound that says so much about the heart that makes the music. There’s no affected vocal, no hokum on the one hand or academic archness on the other. And there could have been, so easily. McCalla’s classically trained; she jumped from a New Jersey upbringing to a New Orleans residency; she’s an American born to Haitian rights activists in the thick of a struggle for democracy; she was an important member of the last incarnation of the much-loved Carolina Chocolate Drops. Her road was ripe for opportunity to leave the music behind in bringing a message that might not have resonated as strongly as it does. But instead she chose on her first solo record, Vari-Colored Songs (2014), to artfully adapt poetry by Langston Hughes and punctuate it with Haitian folk songs. Her second record, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, is also cloaked in a music-first approach that makes the underlying messages — because they are indeed there, as they were in her curation of Hughes’s work — so much more compelling.

Free and blue and beautiful, those moorings Leyla McCalla holds to in her music sway and pitch like the gulf waters from Hispaniola to Lousiana, rolling through her cello and voice and coursing through her songs, lifeblood to an American music heart. In the weaving lines of the music she plays — a snaking, sliding creole so suited to, and perhaps partly a consequence of, the playing of fretless instruments — is the sound of an America taking shape as its many diasporas meet and mix and move, intersecting lines on a map that triangulate on New Orleans. Like the best Americana musicians, McCalla achieves something at once utterly contemporary but steeped in an authenticity of sound that says so much about the heart that makes the music. There’s no affected vocal, no hokum on the one hand or academic archness on the other. And there could have been, so easily. McCalla’s classically trained; she jumped from a New Jersey upbringing to a New Orleans residency; she’s an American born to Haitian rights activists in the thick of a struggle for democracy; she was an important member of the last incarnation of the much-loved Carolina Chocolate Drops. Her road was ripe for opportunity to leave the music behind in bringing a message that might not have resonated as strongly as it does. But instead she chose on her first solo record, Vari-Colored Songs (2014), to artfully adapt poetry by Langston Hughes and punctuate it with Haitian folk songs. Her second record, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, is also cloaked in a music-first approach that makes the underlying messages — because they are indeed there, as they were in her curation of Hughes’s work — so much more compelling.

Like all achieving musicians, Leyla McCalla makes great records and is better in concert, her performances enlivened by the physicality of her musicianship and the communication among her band. In this 2016 performance of “Jogue Au Plombeau,” the band is killing it, in a droning country blues jug-on-pommel trance that I could listen to for hours should they ever decide that that could make sense. Accompanied by violist Free Feral and McCalla’s husband Daniel Tremblay on triangle (who also happens to be one of the more light-touch guitar players I’ve ever seen play live), Leyla McCalla convinces me that all the blues I’ve ever listened to begins here.

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section above.

Bob Dylan is the rare artist who, at 75, retains the power, energy, and restlessness that distinguished his early work. As both a recording and performing artist, his electricity is unabated, and he continues to make vibrant contributions to the post-folk culture he virtually created. That he has achieved this is astounding; for those of us who have followed his career and know something of its roots and evolution, it is not surprising. He constantly recasts his song catalogue, the depth of which by 1965 (let alone 2016) was unrivaled in the rock/folk/singer-songwriter genre he invented, to match his current sound, and commands a fluidity of vision in his writing that sees beyond the trees and perhaps the forest as well. Witness “High Water,” a tribute to Charley Patton (whose “High Water Everywhere” is a stone cold delta blues barking, howling, classic), from 2001’s Love and Theft. This is a blues about love and the water that rises, that has picked up some oldtime, some drone, shaking and breaking and name-checking muscle cars and evolutionary philosophers. The thing is that it works because when Dylan sings “the cuckoo is a pretty bird” that’s a kind of referenced code that he’s hollering back to Patton. He’s writing a blank check to freely associate (find and listen to a version of “The Cuckoo” and you’ll get what I mean), to make the rhyme work and throw meaning to the wind and to the listener. Harder than it sounds because it’s about the sound, what music is, what makes its power inexplicable. To make that warble on the 5th day of July, and trace your absurd and beautiful melody: it takes courage and a resolution that comes at a price only Dylan, and maybe Patton, knows.

Bob Dylan is the rare artist who, at 75, retains the power, energy, and restlessness that distinguished his early work. As both a recording and performing artist, his electricity is unabated, and he continues to make vibrant contributions to the post-folk culture he virtually created. That he has achieved this is astounding; for those of us who have followed his career and know something of its roots and evolution, it is not surprising. He constantly recasts his song catalogue, the depth of which by 1965 (let alone 2016) was unrivaled in the rock/folk/singer-songwriter genre he invented, to match his current sound, and commands a fluidity of vision in his writing that sees beyond the trees and perhaps the forest as well. Witness “High Water,” a tribute to Charley Patton (whose “High Water Everywhere” is a stone cold delta blues barking, howling, classic), from 2001’s Love and Theft. This is a blues about love and the water that rises, that has picked up some oldtime, some drone, shaking and breaking and name-checking muscle cars and evolutionary philosophers. The thing is that it works because when Dylan sings “the cuckoo is a pretty bird” that’s a kind of referenced code that he’s hollering back to Patton. He’s writing a blank check to freely associate (find and listen to a version of “The Cuckoo” and you’ll get what I mean), to make the rhyme work and throw meaning to the wind and to the listener. Harder than it sounds because it’s about the sound, what music is, what makes its power inexplicable. To make that warble on the 5th day of July, and trace your absurd and beautiful melody: it takes courage and a resolution that comes at a price only Dylan, and maybe Patton, knows. On the heels of

On the heels of