One of the hardest things a serious music fan is ever tasked with is coming up with a list of five or ten desert island discs, i.e. the albums without which he or she cannot live. In fact, trying to put such a list together can be torture. I’m pretty sure that somewhere in the Geneva Convention is a prohibition on forcing prisoners of war to assemble a desert island disc list under duress. Such a thing could cause serious and irreversible psychological damage, and would thus be inhumane.

One of the hardest things a serious music fan is ever tasked with is coming up with a list of five or ten desert island discs, i.e. the albums without which he or she cannot live. In fact, trying to put such a list together can be torture. I’m pretty sure that somewhere in the Geneva Convention is a prohibition on forcing prisoners of war to assemble a desert island disc list under duress. Such a thing could cause serious and irreversible psychological damage, and would thus be inhumane.

The trouble with desert island disc lists is that our moods – and thus our musical preferences at any given moment – are so incredibly varied. One moment you might want to listen to the intricacies of a well-played classical guitar piece, the next moment you crave the audio testosterone known as AC/DC. One moment you may want the sunny joy of Led Zeppelin tracks such as ‘The Song Remains the Same’ or ‘Over the Hills and Far Away’, the next moment you want the dark, brooding heaviness of early Black Sabbath. One moment you want the folky feel of some acoustic Jethro Tull, while in another moment you want the cathartic release of an angry Tool song. These examples are just the tip of an infinitely large iceberg.

While I would have to inflict great pain upon myself to assemble a definitive desert island disc list, there is one album I can say would be on any final version that I came up with – Yes’s 1977 masterpiece, ‘Going for the One’.

“Why ‘Going for the One’?” you ask. The consensus on Yes albums like ‘Close to the Edge’ and ‘The Yes Album’ is that they are great albums, if not outright masterpieces. On the other end of the spectrum, albums like ‘Union’ and ‘Open Your Eyes’ are generally considered somewhere between awful and God-awful. And then there are those Yes albums that are lightning rods of controversy – ‘Tales from Topographic Oceans’, ‘90125’, and to some degree, ‘Drama’. ‘Going for the One’, while generally viewed in a positive manner, doesn’t fall into any of these categories among the majority of Yes fans. But if you ask me, it is a masterpiece as much ‘Close to the Edge’. It crystallizes the essence of Yes – not to mention some artistic goals of first-wave progressive rock.

To really ‘get’ this album, it helps to understand the context in which it was recorded, both within the band’s history as well as musical trends at large. Recording for the album began in earnest in the fall of 1976 – the same year that the punk movement exploded onto the scene, in no small part as a reaction to progressive rock. The genre of progressive rock itself was beginning to show some signs of wear and tear – Peter Gabriel had left Genesis, King Crimson had disbanded, and the general excesses of the genre were beginning to turn the music-buying public looking in other directions. Meanwhile, punk was raging and stadium rock’ was beginning to step into the place formerly occupied by the proggers.

Within the band, Yes had gone through a tumultuous few years, including the release of the controversial ‘Topographic Oceans’, Rick Wakeman’s resulting departure, ‘Relayer’, a number of solo albums, a significant amount of touring, the easing out of Patrick Moraz and the eventual return of Wakeman. There was a need for the band to catch its collective breath, to reflect.

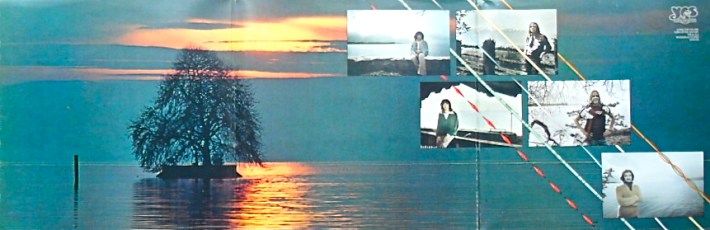

‘Going for the One’ has a very introspective feel to it. This is borne out in no small part by the album artwork, including the cover (shown above) as well as the inner gatefold.

A first thing to note is that none of the Roger Dean artwork is present –neither on the inner gatefold or the outside cover – save for the famous Yes logo. The front cover shows the backside of a naked man, intersected by varying geometric shapes of different lines, against the backdrop of two modern skyscrapers, symbolic of standing naked against modern world. On the inside gatefold is an idyllic scene of a lake at sunset. From the liner notes of the re-mastered CD, I am taking an educated guess that this is Lake Geneva, Switzerland, not far from where the album was recorded. Some sort of island (quite possibly man-made) having a rather large but bare tree sits in the middle of the lake. Individual pictures of each band member are also shown, with all but Steve Howe’s having a lake (the same one?) as a backdrop. The contrast between the front cover and the inner gatefold would suggest taking refuge of some sort, turning inward and reflecting.

In addition to its introspective feel, ‘Going for the One’ also very much has a classical music-like sound as well. In his excellent book ‘Rocking the Classics’, author Edward Macan describes progressive rock of the 1970’s as attempting to “combine classical music’s sense of space and monumental scope with rock’s raw power and energy.” ‘Going for the One’ accomplishes this spectacularly, better than any other progressive rock album of the 70’s, other Yes masterpieces included. The introduction of the harp and the church organ, the latter from St. Martin’s Cathedral in Vevey, Switzerland, are instrumental in the sound of this album. The sound here exemplifies the term “symphonic progressive rock.” Interestingly enough, this was the first Yes album since ‘Time and a Word’ that did not feature Eddy Offord in the role as a producer. There is little doubt Offord’s absence affected the overall sound.

The title track kicks off the album, and it is an outlier with respect to the remainder of the tracks – a straight ahead rocker. In yet another “first in a long time”, the title track of ‘Going for the One’ is the first Yes song under eight minutes in length since Fragile. Between ‘Fragile’ and ‘Going for the One’, the shortest Yes song was ‘Siberian Khatru’, clocking in at 8:55. Musically, the song is propelled forward by Howe’s pedal steel guitar. This is interesting in itself, as the instrument is most closely associated with country music, yet Howe makes it rock and rock hard here. Wakeman’s keyboard work, both on the church organ and piano stand out here as well. In general, every instrument here, as well as the vocals, proceeds at an up tempo pace that maintains itself from start to finish.

There are a two other things to note on the title track that are true for the entire album. One is that the production here is very crisp and clean. The second (which undoubtedly plays on the first) is that the soundscape is not as dense as on the album’s predecessor, ‘Relayer’. Instead of choosing to fill up every available recording track, the band has scaled things down a bit from their previous effort. This is done to good effect, as it gives the music a little more chance to breathe.

The classical-like sound referenced above makes its first appearance on the next track, ‘Turn of the Century’, and is prominent from here on out. The music begins with some light, exquisitely played acoustic guitar work by Howe. Jon Anderson has stated the song was inspired by Giacomo Puccini’s ‘La Bohème’, and lyrically it tells a story of a sculptor creating his lover in “form out of stone” after her death. Both music and lyrics convey a sense of deep loss, making this the album’s most emotional piece. The loss is most poignantly conveyed in the first half of the song, when the music is very melancholy. Around the halfway mark, Wakeman’s piano makes an appearance, along with Howe’s pedal steel guitar. This evolves into a very tumultuous transition. But what emerges on the other side, in the latter half of the song is bright and joyful. Howe takes over on a standard electric guitar with some very sunny lines, while Squire’s bass line does a great job of playing off of Anderson’s vocals. Moreover, this portion of the music is very joyful, indicating that our protagonist has emerged from his grieving and can once again experience happiness. Perhaps the sculpture of his lover has given him solace and peace, coming to life metaphorically if not in reality. The ending of the song has a bittersweet feel to it, as if again to acknowledge the loss while also acknowledging the ability to find joy in life once again after such a tragedy. All things considered, this is a very beautiful and delicate composition both musically and lyrically.

‘Parallels’ is up next, and is an underrated gem of the Yes catalog. This song features spectacular performances by Howe, Wakeman, and Squire, who take turns in showing off their chops on their respective instruments. Still, they never descend into self-indulgence or stray from the song’s logical progression. The song introduces itself proper with Wakeman’s billowing church organ from St. Martin’s Cathedral ( this is best played LOUD to get the full impact). Squire and Howe then chime in, the former with a typically excellent bass line, the latter with some crisp, clean lead guitar. From there, the song takes on a straightforward structure of two verses and two choruses, before transitioning into the middle section led by more of Howe’s crisp lead guitar. After another verse, the song segues into an instrumental section in which Wakeman and Squire are at the forefront. The interplay between Wakeman’s soloing on the church organ and Squire’s bass line is nothing short of brilliant. The transition out of this instrumental section is announced by the return of Howe’s guitar. After one final chorus, the song begins barreling toward its conclusion. Howe again steps to the forefront, his guitar firing burst after burst of clean, high notes. This is some of my favorite Howe guitar work in the entire Yes catalog – bright, sharp, and technically brilliant. Squire and Wakeman remain in the mix here with some fantastic playing of their own.

Another defining aspect of ‘Parallels’ is its conclusion – one of the best endings to a song I have ever heard. That ending is more easily described in non-musical terms. Imagine 18-wheeler, barreling down the highway at full speed. Now imagine that 18-wheeler not just coming to a full stop, but stopping on a dime. And imagine that 18-wheeler doing so with the grace and finesse of a ballet dancer. That’s the ending of ‘Parallels’ right there. It’s an extremely difficult combination to pull off, which makes its flawless execution here that much better.

If J.S. Bach had a rock band, it would sound like ‘Parallels’.

Moving on, we next come to ‘Wonderous Stories’. It’s the shortest song on the album, but also the brightest. It also marks the return of Howe on a guitar-like instrument called the vachalia, which last appeared on ‘I’ve Seen All Good People’. Like ‘Parallels’ before it, the song includes a verse-chorus structure, with the choruses featuring some of Yes’s trademarked harmony vocals. The middle section is marked by a rather vigorous Wakeman keyboard solo including synths that emulate a string section. The song resumes its verse-chorus structure once again, while a thick bass line underneath propels the music forward. Howe and Wakeman continue to supply the melodies on top. The vocals, which include both harmonies and counterpoints here, are stunning. As the vocals fade out, Howe enters the scene again, this time with some jazzy electric guitar to close out the song.

Finally, we come to ‘Awaken’. There are numerous superlatives which could be used to describe this piece. All of them are inadequate. Somebody will have to invent new ones.

Much like the album ‘Moving Pictures’ did for Rush, ‘Awaken’ brings together everything that is great about Yes and distills it into one coherent work of art. It has the epic scope of pieces such as ‘Close to the Edge’ and ‘Gates of Delirium’. It has the virtuoso instrumentation of numerous Yes classics such as ‘Heart of the Sunrise’, ‘Yours is No Disgrace’, and ‘Siberian Khatru’. And it has the classical feel of the preceding tracks on the same album. Moreover, it pares back some of the excesses of previous albums without paring back any of the artistic ambition.

To the uninitiated, Wakeman’s piano lines that open ‘Awaken’ could be mistaken for something from a piano concerto. After a few vigorous runs, the music begins a dreamy sequence, as Anderson’s vocals begin. As the introductory verses closes, a note of dissonance sounds before Howe takes over using a guitar riff that has a decidedly Eastern flavor (incidentally, the working title for ‘Awaken’ was ‘Eastern Numbers’). Anderson begins a chant, and the music takes a more serious tone. The most remarkable thing about this section is the drumming and the bass work. Alan White’s drumming with Yes has never been better than on this album, and on this particular track. Squire’s bass plays off of both White’s drumming and Howe’s guitar. The odd time signature here keeps things more than interesting, as it is difficult to predict when the next bass note or next drum beat will fall, and yet it’s also clear that there is a logical pattern behind the playing. It’s the kind of bass and drum work that sucks the listener in and keeps them hooked.

After two verses and two choruses of the chant, the music breaks into a blistering Howe guitar solo. Much like the guitar work on ‘Parallels’, the soloing here is full of bursts of sharp, high-pitched notes. However, the mood here is entirely different, expressing a sense of inner turmoil and urgency. This is another section of brilliant virtuoso guitar playing that illustrates why this album is among Howe’s strongest, either in or out of Yes.

As Howe gracefully exits the solo and returns to the main riff, another verse and chorus of the chant follow before the music begins a slow transition away from the Eastern motif. Wakeman’s keyboards step to the forefront, first mirroring Howe’s riff before segueing into the “Workings of Man” portion of the song. The church organ leads the way into this section, which has a much more European sound and texture, not to mention the lyrics. The tension builds here to a peak before Wakeman puts the brakes on the whole thing with a series of ever quieter notes, effectively bringing the first half of ‘Awaken’ to a close.

The transition to the second half of the song begins with a split-second of silence, before a single note of White’s tuned percussion blends into the first pluck of a harp by Anderson. From an initial quiet beginning, the band begins to slowly and painstakingly build tension in what is a textbook example of the technique. White’s percussion and Anderson’s harp start this section, soon to be joined by Wakeman, who is initially playing singular notes on the church organ.

The transition to the second half of the song begins with a split-second of silence, before a single note of White’s tuned percussion blends into the first pluck of a harp by Anderson. From an initial quiet beginning, the band begins to slowly and painstakingly build tension in what is a textbook example of the technique. White’s percussion and Anderson’s harp start this section, soon to be joined by Wakeman, who is initially playing singular notes on the church organ.

A layer is added to the tension when Wakeman begins playing slightly longer (but still relatively quiet) runs. Squire also quietly enters, playing singular high bass notes, most likely on the six-string neck of the monster triple neck bass he uses for live performances of this song. These bass notes intensify and push the music forward, while Wakeman’s runs on the church organ slowly begin to lengthen, increase in volume, and sound more orchestral. Choral singers also join the fray, further building the intensity, which builds like a wave to a first peak before receding somewhat. At this point, Howe re-enters the picture on electric guitar, and leads the music to a second peak and a transition into what may be called the ‘Master of Time’ section of the piece. The build-up from the initial plucks on the harp to this point is powerful stuff, very mesmerizing and very emotional.

I have a personal anecdote I would like to share to illustrate the emotional punch of this section. In 2002, I attended my sixth Yes concert at an excellent Austin venue called The Backyard. I went with several former co-workers, including a friend of mine named Cheryl. While Cheryl is not a prog rock fan per se, she is much more of an astute listener to music than the vast majority of people. Musically, she is “switched in”. Toward the end of the concert, Yes performed ‘Awaken’. During the portion described above, I was mesmerized as normal, but for some reason I looked over at Cheryl standing next to me to gauge her reaction. Tears were streaming down her face, which was transfixed to the stage as she was as absorbed in the music as I had been just before turning my head. Amazing. I remember thinking “she gets it”, and was very impressed at that. Among my friends and acquaintances, I have musically usually been an outlier, as few of them have been interested in prog, and certainly not anywhere to the same degree as me. Some of them have even heard ‘Awaken’ in my presence and have given me strange looks that say “what the heck is this?” Yet here was Cheryl, on her first listen to ‘Awaken’, completely getting the gist of this incredible composition. As someone who had known this little secret for a long time, I found it very gratifying to see her reaction with no prompting or no explanation from anyone else – only the music was talking. It’s a moment I will not soon forget.

As the music progresses through the ‘Master of Time’ section, Anderson sings several verses and the tension continues to build, finally resolving itself with a shattering climax, with Wakeman’s church organ and the choral singers at the forefront. The dreamy section from the beginning is then reprised, and the final line of lyrics is one of my favorites from the entire Yes catalog: “Like the time I ran away, and turned around and you were standing close to me.” Howe then brings ‘Awaken’ to its final conclusion with some playful electric guitar lines.

Wow. What a piece of music. In my opinion, the finest fifteen minutes plus of music Yes ever committed to any recording medium. This is not to take away anything from some of their other masterpieces (and there are several), but to extol the virtues of this incredible piece of music. And by the way, I am in some good company when I surmise that this is Yes’s best work. None other than Jon Anderson himself has stated “at last we had created a Masterwork” with regard to Awaken. On the 1991 documentary ‘Yesyears’, Anderson refers to “the best piece of Yes piece of music, Awaken” and further states that it is “everything I would desire from a group of musicians in this life.” I’d say that’s a pretty strong endorsement.

In progressive rock circles, many references are made to the various sub-genres. Yes music (at least their 70’s output) is most often classified as symphonic progressive rock. No album exemplifies this term more perfectly than ‘Going for the One’, and no song exemplifies it more than ‘Awaken’. Other Yes works, such as the previously mentioned ‘Close to the Edge’ and ‘Gates of Delirium,’ possess the same scope but not the same instrumental timbre. ELP had some symphonic works that were their own interpretations of existing classical compositions while their own magnum opus, ‘Karn Evil 9’, sounded high tech for its time. ‘Thick as a Brick’ by Jethro Tull is certainly symphonic in its scope, and while great in its own right, has more of a folky feel than symphonic. In contrast to all of these, on ‘Going for the One’, Yes has created original compositions that, in many parts, could be easily mistaken for classical symphonic music by those not otherwise familiar with this type of music. A perfect fusion, you might say.

I’m still struggling to come up with the other four or nine or however many albums I need to complete my desert island disc list. And being immersed in the midst of a second golden age of progressive rock as we are now, completing that list will only get tougher due to the cornucopia of excellent new releases. But I can say without any hesitation, without any equivocation, whatever final form that list takes, it will most definitely include ‘Going for the One.’