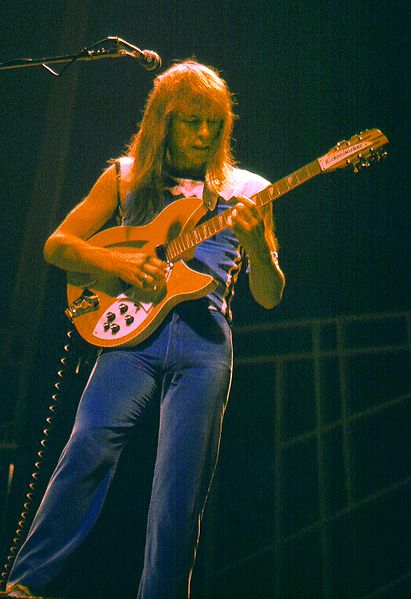

Someone with time on their hands and prog trivia on their brains should do some careful historical research in search of the answer to this question: “Which prog group has the most line-up changes all-time?” Three groups come to mind immediately: Yes, Asia, and King Crimson. And the three are, of course, bound together by all sorts of personnel connections and such, as  well as having been around for decades, which surely is part of the ongoing drama of departing, returning, reuniting, breaking up, reforming, guesting, and so forth. Anyhow, legendary guitarist Steve Howe has announced that he is leaving Asia so he can concentrate on solo work and (it appears) his commitments to Yes. Just as (or more) interesting are his remarks on playing guitar. From the ProgRockMag.com site:

well as having been around for decades, which surely is part of the ongoing drama of departing, returning, reuniting, breaking up, reforming, guesting, and so forth. Anyhow, legendary guitarist Steve Howe has announced that he is leaving Asia so he can concentrate on solo work and (it appears) his commitments to Yes. Just as (or more) interesting are his remarks on playing guitar. From the ProgRockMag.com site:

The pressures of attending to the requirements of two large-scale acts was also getting to him, he admits. “Over the last year I started to think, ‘Boy, when Yes extend a tour then Asia start a day early, I’m the guy getting squeezed.’ I couldn’t do it much longer without feeling that I was running on autopilot. I want to be in control of my musical direction and follow my calling.”

That calling will include the Cross Styles Music Retreat, during which Howe hopes to share his passion and experience of guitar with attendees. But he’s wary of the “unique” label: “It sounds like I’ve set myself up for a fall there,” he laughs. “All I’m saying is: I’m not educated, I don’t read music, I didn’t go to music school, I don’t have the theory. All I have is my experience, and presumably people want that, otherwise I wouldn’t be selling any tickets.

“I’ve done these things before. I walk in and say, ‘Don’t talk to me about demi-semiquavers. Don’t talk to me about time signatures.’ I play. Everything I do and everything I’ve learned is by ear.

“You don’t have to drive yourself mad reading dots. If you want to play classical music you should; but where I’m coming from, improvisation, composition. I’m bringing in an unschooled – I wouldn’t say rebellious, but individual – approach to guitar.

“I’m not going to pose that it’s going to be anything else. You get me, I play tunes and I talk about guitar. I’ve managed to make that interesting for myself for over 50 years, so there must be something!”

Howe states that he’s never believed in straight-out practising. “Playing scales would have driven me stark raving bonkers,” he says. “That’s not what I call music. It might be an essential part of keeping your muscles and fingers in good order and I don’t say it’s terrible. But my central thing is improvisation. Play stuff – make stuff up. That’s how I keep interested: by interacting with it, not just being a mechanical, physical observer.”

He didn’t enjoy his school days, finding London’s Holloway School “oppressive, violent, mixed with racial and religious prejudices.” But he’s never found that a lack of a “proper” musical education held him back – except when he tried to learn to play flute and discovered it was too distant from guitar to make the transfer comfortable.

As a result of being self-taught he does encounter people who are better technicians than he is. “But I don’t feel particularly threatened,” he explains. “What I feel is: ‘They’re very advanced in their technique – how advanced are they in their general view of music?’

“Guitarists can get fanatical about guitarists; but in the end we’re musicians. We make sound. It’s the sound that’s got to be pleasing – not how you made the sound. Who cares how you play it? What’s important is what comes out the other end.”

And one of the key lessons he hopes to impart at Cross Styles is: “Musicians are lucky; we can break the rules. There’s no such thing as the ‘music police’ – they’re not going to come round and say ‘You shouldn’t have played a D-flat, it should have been a D. You can do what you want – live and die by the musical sword!”

In addition to the retreat he’s planning a solo tour and a new Steve Howe Trio album and tour. “We’re just about to launch some dates. I’ve got two or three weeks of solo dates in June, which I haven’t done in a very long time due to my demanding schedule of keeping two bands happy. In September we’re doing the trio again. We should have a new recording before that.”

His desire to move away from the band environment is much more than just a whim, Howe notes. “My solo guitar work is pretty central to my musical existence. I’m not a blues, rock or jazz guitarist – I’m a guitarist, and the central thing is solo playing.

Read the entire piece. Glancing over his bio on Wikipedia (yes, I know, forgive me), I was a bit surprised to learn that Howe was the first player to be inducted into the Guitar Player Hall of Fame, and one of the few in the GP’s “Gallery of Greats”, which comes with being selected best overall guitarist at least five times (although it appears the criteria has now been modified). Howe’s playing has long intrigued me because of the obvious jazz influences; he was influenced by Wes Montgomery, as well as Chet Atkins, whose mark on Howe can be seen in Yes songs that have a country-type feel to them, quite unique within the prog realm.