With deep roots in the mountains of north Georgia, young Hedy West presented authenticity and authority in her singing of old time folk music. By the early 1960s she had become a mainstay of the growing traditional music revival in America, having written the often-covered “500 Miles” and dazzling audiences with her fluid clawhammer banjo style and clear, naturally inflected, singing voice. By the mid-1960s she was touring Europe, singing and playing with like-minded fellow travelers of the British folk revival. But if you’ve heard of Hedy West, even if you’re acquainted with the American and British folk revivals, you’re an exception. She kept a low profile, and her career as a musician was wrapped tightly with her political activism. She was no rock star — although many thought her the best of the “girl” folk singers of the era.*

With deep roots in the mountains of north Georgia, young Hedy West presented authenticity and authority in her singing of old time folk music. By the early 1960s she had become a mainstay of the growing traditional music revival in America, having written the often-covered “500 Miles” and dazzling audiences with her fluid clawhammer banjo style and clear, naturally inflected, singing voice. By the mid-1960s she was touring Europe, singing and playing with like-minded fellow travelers of the British folk revival. But if you’ve heard of Hedy West, even if you’re acquainted with the American and British folk revivals, you’re an exception. She kept a low profile, and her career as a musician was wrapped tightly with her political activism. She was no rock star — although many thought her the best of the “girl” folk singers of the era.*

Following Hedy’s death in 2005, a collection of recordings and papers — including hundreds of tapes of interviews with her grandmother Lillie Mulkey West that in themselves are a storehouse of Appalachian culture — made their way to the special collections library where I worked at the University of Georgia. As my colleague Christian Lopez and I started working through some of the boxes in 2010, we found pictures Hedy had taken of two young men in a flat, sometime in the mid to late 1960s. We were flabbergasted: they were Dave Swarbrick and Martin Carthy. Both of us were fans of these two, knew their work and their cultural impact on British rock and folk music. And it’s an interesting thing, Hedy taking these pictures. Like West, fiddler Swarbrick and guitarist Carthy were leading lights of their folk revival, in Britain, often recording as a duo. According to Swarbrick, in an email response to Christian, the three traveled Europe together, and it was “on the banks of a river in the former Yugoslavia” that Hedy played for Swarbrick and Carthy a tune called “Maid of Colchester.” Why, you might ask, was Christian emailing the ailing Dave Swarbrick regarding this tune, and why should it be important in any way? To condense a long story, I started as a Martin Carthy fan because I was a Steeleye Span fan because I was a Jethro Tull fan. And, by the time I saw Carthy play his adaptation of “Famous Flower of Serving Men” in 1991 in a community center in a London suburb, also on my radar was the tune “Matty Groves,” from Fairport Convention’s live record, House Full (recorded 1970, released 1986 — of course, “Matty Groves” was the epic track of their seminal album, 1969’s Liege and Lief). Swarbrick was Fairport’s fiddler on these records, and anyone familiar with British folk-rock and with half an ear knows that the central tune for “Famous Flower of Serving Men” is identical to the extended jam-band outro of “Matty Groves.” Carthy identifies the tune to “Famous Flower” in the liner notes to 1972’s Shearwater as “Maid of Colchester,” learned from one Hedy West. Christian had emailed Swarbrick to see if we could close the loop, since Fairport’s “Matty Groves” pre-dated Carthy’s song. Swarbrick confirmed that his and Carthy’s source for the tune was the same, and it was indeed Hedy West. Our minds were fairly blown. Two keystone songs of the British folk revival and British folk rock rely on a riff brought (back?) from America, by a woman who as far as we know never recorded the tune herself.

As sung by Sandy Denny in 1969, “Matty Groves” is a song of adultery and tragic murder that became the centerpiece — along with the riff monster “Tam Lin” — of Fairport’s pinnacle album. Denny and founding bassist Ashley Hutchings left Fairport weeks after the release of Liege and Lief, and while Richard Thompson would stay for one more album, by 1971 he had embarked on a solo career. But between the departure of Denny and Thompson, Fairport Convention hit its stride as a live band, touring widely. For the first time without a female lead singer, the group indulged its triple attack of guitarists Simon Nicol, Thompson, and fiddler Swarbrick, trading vocals depending on the tune. The addition of Dave Pegg on bass gave them a heavier sound, and what sounded on Liege and Lief a bit thin was overpowering and raw live. By the time they hit a residency at the Troubadour in Los Angeles in September 1970, they were on fire, delivering absolutely devastating versions of Thompson’s new song, the mighty “Sloth,” as well as a huskier, rocked-out “Matty Groves.” With Thompson singing lead and the others in support, the tale takes on a dark, derelict tawdriness, unlike the tragedy it was in Denny’s reading, and when at the break they launch into, yes, “Maid of Colchester,” they may as well have been the greatest rock band on earth. At breakneck speed, Thompson demonstrates why he is who he is, while Swarbrick’s performance is electric and Dave Mattacks’s drumming dependably dynamic and fully engaged, as it always was and is. According to Joe Boyd, Fairport’s producer — for who else would it be — during Fairport’s stay at the Troubadour Led Zeppelin stopped by, sat in, and the music that happened was “not fit for a family album.” No doubt Zep loved their Fairport, if only based on the evidence of Denny’s presence on “Battle of Evermore,” but beyond that there is in this music a ragged-but-right universal tone that both bands were following at the time and in their own ways. As Hedy and others before them had done, they took what they needed from the ancient songbag and made it something else, in the spirit of Art.

*This from A.L. Lloyd, who was sort of Britain’s Pete Seeger. Seeger, for his part, also held Hedy in high esteem.

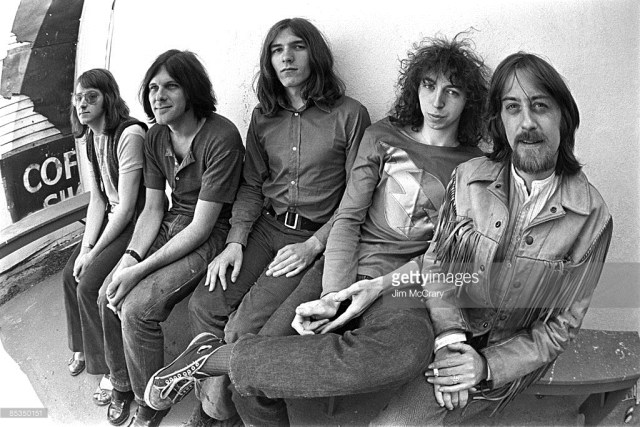

Image above: Dave Mattacks, Dave Pegg, Simon Nicol, Richard Thompson, Dave Swarbrick, 1970.

In 1977, the same year Jethro Tull recorded

In 1977, the same year Jethro Tull recorded