Few bands seem to cause such division as Simple Minds. There are fans of the early stuff, fans of the later stuff, fans of New Gold Dream…. I never had a horse in that race, since I never particularly cared to follow them. I liked what I heard on the radio of theirs well enough, it was certainly expertly crafted and, in retrospect, helped define its time. But recently I felt like mining a bit deeper and came upon their early records. I understand the early fans’ passions more now, since it’s made clear on Real to Real Cacophony and Empires and Dance that the band was chasing an ambition to recast pop music coming out of the 70s. That they caught up with it is apparently a deep disappointment for those who read sellout in the tracks of Once Upon a Time, but of course the one — a deeply enjoyable confection of well-honed hooks and musicianly smarts, no matter its commerciality — would not have been possible without the other, a proving ground that was hit and miss, but when it found its mark was incendiary.

Few bands seem to cause such division as Simple Minds. There are fans of the early stuff, fans of the later stuff, fans of New Gold Dream…. I never had a horse in that race, since I never particularly cared to follow them. I liked what I heard on the radio of theirs well enough, it was certainly expertly crafted and, in retrospect, helped define its time. But recently I felt like mining a bit deeper and came upon their early records. I understand the early fans’ passions more now, since it’s made clear on Real to Real Cacophony and Empires and Dance that the band was chasing an ambition to recast pop music coming out of the 70s. That they caught up with it is apparently a deep disappointment for those who read sellout in the tracks of Once Upon a Time, but of course the one — a deeply enjoyable confection of well-honed hooks and musicianly smarts, no matter its commerciality — would not have been possible without the other, a proving ground that was hit and miss, but when it found its mark was incendiary.

“Premonition” has at its center a chunky classic rock riff driven by Charlie Burchill’s guitar, and isn’t too distant from what the Cars and Tubeway Army were doing at a time before the keyboards really took complete hold, combining the ethic of early Roxy Music with a post-punk focus on rhythm (Derek Forbes and Brian McGee brought genius to this band). Jim Kerr sings with a wide-eyed weirdness straight out of Marquee Moon, while Mick MacNeil’s carnivalesque keyboarding from this time must have influenced fellow Glaswegians Belle & Sebastian (thinking specifically of “Lazy Line Painter Jane”).

This live rendition — though honestly the sync seems odd enough to me and the recording good enough that there may be some yet-to-be-defined disconnect between picture and sound — catches Simple Minds in their early prime (and goes some way to explaining why they were offered a certain song to sing for a certain movie after Bryan Ferry turned it down). They were catching fire creatively, figuring it out and putting it out live. That their trajectory afterwards went on to follow that of Ferry et al. is perhaps the sign of one common path in a larger creative process tied to myriad motivations. Me? If I had to decide which Simple Minds I prefer…I’d take both.

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section above.

In completing a year of soundstreamsunday, I turn away from the “infinite” in the project’s subtitle (

In completing a year of soundstreamsunday, I turn away from the “infinite” in the project’s subtitle (

The principles of exclusion, constraint, and limitation are drivers of art as much as what ends up on the canvas, and more than anything explain how U2’s “The Three Sunrises” did not make the cut of their seminal 1984 album The Unforgettable Fire. That album, their fourth, changed the band’s trajectory by broadening their palette (thus ultimately guaranteeing their longevity). Subduing the band’s onward-Christian-soldier martial airs without dulling its passion, producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois — who the previous year had created, along with Roger Eno, one of the great ambient masterworks in Apollo — worked at applying creative filters to make a music that was moody, introspective, less deliberate but also more whole. The Unforgettable Fire feels more like an album with a sonic narrative than any of its predecessors. Still, no one, not even Eno, could contain U2’s spirit or strong self-identity, and the recording sessions yielded some work with one foot still grounded in the energetic brightness characterizing their previous catalog.

The principles of exclusion, constraint, and limitation are drivers of art as much as what ends up on the canvas, and more than anything explain how U2’s “The Three Sunrises” did not make the cut of their seminal 1984 album The Unforgettable Fire. That album, their fourth, changed the band’s trajectory by broadening their palette (thus ultimately guaranteeing their longevity). Subduing the band’s onward-Christian-soldier martial airs without dulling its passion, producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois — who the previous year had created, along with Roger Eno, one of the great ambient masterworks in Apollo — worked at applying creative filters to make a music that was moody, introspective, less deliberate but also more whole. The Unforgettable Fire feels more like an album with a sonic narrative than any of its predecessors. Still, no one, not even Eno, could contain U2’s spirit or strong self-identity, and the recording sessions yielded some work with one foot still grounded in the energetic brightness characterizing their previous catalog. Keith Jarrett

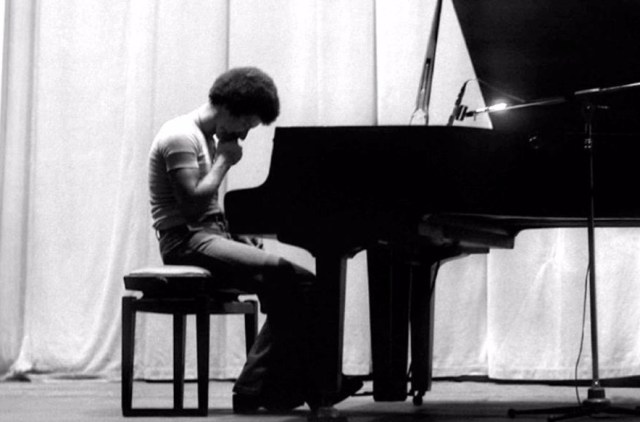

Keith Jarrett It’s 1975 and I’m nine years old. I’m lying on my back in Reservoir Park, a small city block of grass and oaks next to the University of Utah. In my head is a song that trips and travels as I run and play with friends. It’s a vision of sound, a strong impression of bright sun and moving clouds, a feeling on my skin, a growing chill in the air. Is it October? The song is a constant rhythm of consciousness and motion, a life in itself but also within me, as if I’m one of its many, many tributaries.

It’s 1975 and I’m nine years old. I’m lying on my back in Reservoir Park, a small city block of grass and oaks next to the University of Utah. In my head is a song that trips and travels as I run and play with friends. It’s a vision of sound, a strong impression of bright sun and moving clouds, a feeling on my skin, a growing chill in the air. Is it October? The song is a constant rhythm of consciousness and motion, a life in itself but also within me, as if I’m one of its many, many tributaries. Even with an acknowledgment that the guitar crossroads intersect and break and branch through

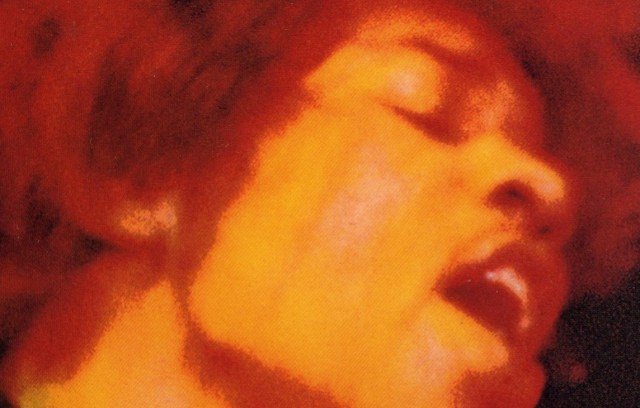

Even with an acknowledgment that the guitar crossroads intersect and break and branch through  Jimi Hendrix’s mystery is something not quite capture-able as an iconographic or intellectual thing. Even knowing some of the details of his background — from his emergence on the chitlin circuit to his being shepherded to London by Chas Chandler — doesn’t explain the lightning the man conjured. The scant year and a half that Hendrix and his Experience released their three albums (May ’67-October ’68) encompassed a sea change in rock music that saw a full embrace of

Jimi Hendrix’s mystery is something not quite capture-able as an iconographic or intellectual thing. Even knowing some of the details of his background — from his emergence on the chitlin circuit to his being shepherded to London by Chas Chandler — doesn’t explain the lightning the man conjured. The scant year and a half that Hendrix and his Experience released their three albums (May ’67-October ’68) encompassed a sea change in rock music that saw a full embrace of  A deep blues, a call to enlightenment, a psychedelic spiritual of epic proportions, Pharaoh Sanders’ “The Creator has a master plan” rings with a disciplined clarity one might expect from a former

A deep blues, a call to enlightenment, a psychedelic spiritual of epic proportions, Pharaoh Sanders’ “The Creator has a master plan” rings with a disciplined clarity one might expect from a former  The art gallery of rock and roll is a rich and welcoming place, with room upon room spinning off into many-directioned distances. There is no entrance fee or warnings to stand back, please, from the piece. And, like at all great museums, any pretense to surface comportment is, if meaningful at all, only a nod of respect to the spark of human creativity. A sign that we don’t stand in willful ignorance. Before the work, within the work, we are all children. It is in rock’s nature to empower its listeners to create, and within this space there is no genre, no boogie no punk no progressive no pop no indie no folk, just an honoring of the empty canvas and the unrestrained fire banked down in humanity. It’s what I love about rock, and it’s what made Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks happen.

The art gallery of rock and roll is a rich and welcoming place, with room upon room spinning off into many-directioned distances. There is no entrance fee or warnings to stand back, please, from the piece. And, like at all great museums, any pretense to surface comportment is, if meaningful at all, only a nod of respect to the spark of human creativity. A sign that we don’t stand in willful ignorance. Before the work, within the work, we are all children. It is in rock’s nature to empower its listeners to create, and within this space there is no genre, no boogie no punk no progressive no pop no indie no folk, just an honoring of the empty canvas and the unrestrained fire banked down in humanity. It’s what I love about rock, and it’s what made Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks happen. In 1966-1967 Los Angeles was Arthur Lee’s dark kingdom. Brian Wilson owned the sun, Jim Morrison traveled the other side, and while the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield gave L.A. its folkie hippie face, Lee’s band Love fashioned a punk muzak masquerade that fifty years on will still not relent. Their capstone album, 1967’s Forever Changes, is one of the handful of perfect rock records, but it is a difficult masterpiece, borne of a drug-addled band falling apart on the heels of some minor pop success (thanks to their cover of Bacharach/David’s “My Little Red Book” and the blazing protopunk of “7 and 7 Is”), as their chief admirers and competitors the Doors were surpassing them in popularity, commercially beating them at their own game. Forever Changes is not instantly recognizable for what it is, and its easy melodic beauty — indebted to the Tijuana Brass, smooth jazz, and surf instrumentals — supports a poetry far more complex and subtle than anyone else in rock was writing at the time, save perhaps Van Morrison.

In 1966-1967 Los Angeles was Arthur Lee’s dark kingdom. Brian Wilson owned the sun, Jim Morrison traveled the other side, and while the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield gave L.A. its folkie hippie face, Lee’s band Love fashioned a punk muzak masquerade that fifty years on will still not relent. Their capstone album, 1967’s Forever Changes, is one of the handful of perfect rock records, but it is a difficult masterpiece, borne of a drug-addled band falling apart on the heels of some minor pop success (thanks to their cover of Bacharach/David’s “My Little Red Book” and the blazing protopunk of “7 and 7 Is”), as their chief admirers and competitors the Doors were surpassing them in popularity, commercially beating them at their own game. Forever Changes is not instantly recognizable for what it is, and its easy melodic beauty — indebted to the Tijuana Brass, smooth jazz, and surf instrumentals — supports a poetry far more complex and subtle than anyone else in rock was writing at the time, save perhaps Van Morrison.