Two years on from our first chat, Alberto Bravin of Big Big Train joins us again to bring us the inside scoop on the superb new BBT album Woodcut, released February 6th on Sony’s InsideOut label. (Woodcut is available for preorder on CD, CD/BluRay combo and vinyl from The Band Wagon USA and Burning Shed. Andy Stuart’s companion book Woodcut: The Making and the Meaning from Greg Spawton’s Kingmaker Publishing is also available.)

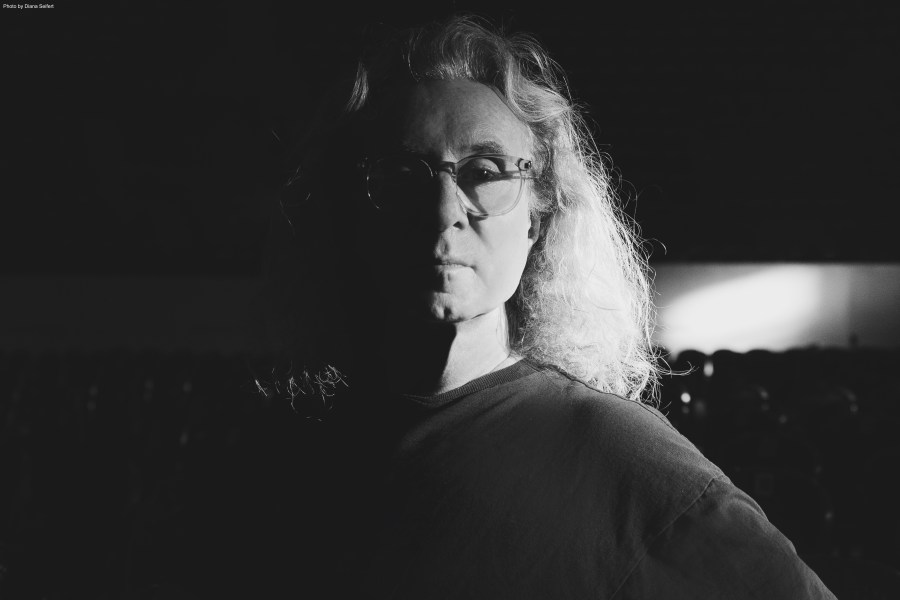

For Woodcut, Alberto was in on the genesis of the album concept and composed a substantial chunk of the material; in the studio, he sang lead vocals, played guitar and keys, and produced the whole thing – so he has plenty to share about its creation! A lightly edited transcript of our conversation follows the video.

So, first of all, congratulations on Woodcut. I’ve been able to listen to it and I’m really impressed and moved by it. It’s a powerful album.

Oh, thank you. Thank you very much.

You’re welcome. So, what was the original spark for its concept?

So, it was really random. Because we never talk about doing a concept seriously. Like, sitting down and saying, “Okay, we’re doing a concept album now.” We’ve never done it. So, me and Greg, we were on tour. We were in Oslo at the [Edvard] Munch Museum.

Okay.

And it was just me and Greg. I mean, we wake up early. We like to have a walk in the early morning. So, we went there and it’s an incredible place. Really, really nice. And everybody knows Munch for “The Scream.” That it’s his most famous painting. But I didn’t know, he actually made a lot of woodcuts.

So, we were there and there was a part of the museum about these woodcuts. And I know what a woodcut is. But I didn’t know that in English you call it woodcut. I knew the Italian word, but not the English word. So, as soon as I’ve seen the name woodcut, I just looked at Greg. And Greg looked at me and we said, “Oh, this is the title of a concept album!”[Laughs]

So, that moment was the actual spark of the concept. And we had no music, no story, no lyrics, nothing; it was just the title. And we started to work from there. [Laughs]

So, once you had that brain spark, how did the rest of the band react? And how did you go about fleshing out what would come from just that word association?

So, as I said, we were on tour. We were like on the bus together. And I think that night or maybe the day after, we just thought about it, me and Greg. And we said, “I think this is a good pitch to tell them what it could be about.” At the beginning, the idea was to write a story about Munch. That was the first idea. “Oh, he has an interesting story; it could be interesting.”

But then we wanted to have a little bit more freedom on the story. So, we kind of invented our own artist there. But we had this idea of a struggling artist. And it could have been something a little bit more magical. And the idea was to have kind of a dark album. But with the Big Big Train stamp on it.

So, we just told the other guys! Like a stream of words and stuff. And everybody was, “oh, this is great! Let’s do it!” And from there, everybody was aware of this. And everybody wrote some ideas or some songs or some melodies and stuff, and put it on a Dropbox folder. And then we started from there. We started from the music, actually. The lyrics came later.

Okay. And I know that happens a lot in the rock and roll field. You get the music and then you get the lyrics to go with it.

Yeah.

It’s also interesting to me, because certainly in Big Big Train’s history, there’s been this sense of craftsmanship. Of creativity. You see that in the lyrics. You see that in the sort of artisan, bespoke way the band has been run for such a long time. But it’s interesting that you decided to go in a slightly darker direction with it. That’s not necessarily what people have come to expect. Which I suppose is one reason to do it!

No, absolutely. I mean, if it’s easy, [laughs] I don’t like it. I want to do, every time, something different. And the approach was really different from The Likes of Us, the previous album, where we had some songs that were already there. And we kind of went for the Big Big Train way. Everything sounded, apart from the singer of course, like Big Big Train.

I think this time – this is just the photo of the band now. So there was nothing like a thought or something that we sat down and said, “Oh, we have to do this.” It was just so easy! We just wrote those songs and I put them together. And it just sounds like us now.

Well, yes. A couple of things pop in my head. First of all, I’ve seen you guys live twice with you in the lead. And both times I’ve noticed, wow, these guys really like each other and really like playing with each other. That vibe is constantly coming off the stage.

Oh, yeah.

And the other thing that I noticed when I was listening to Woodcut, I mean, it doesn’t have one extended track. The whole thing has that sense of organic growth, of heading for a destination.

Yeah.

And my question was going to be, did that fall into place? Was it a lot of hard work to get there? Or was it kind of both of the above?

It was a crazy amount of work. I mean, we had this folder with a lot of songs, songs and melodies, ideas and stuff.

From day one, I had the idea of, “If we’re doing a concept album. It’s going to be a proper concept album, like one hour of music. No stop. You cannot skip it. [Laughs] You have to listen to it.” So, yeah, the idea was that. Like a flow, like everything had to be linked and everything like this one song when it’s going to go into the other.

And so I put all the ideas and all the songs and all the melodies in a Logic project, like the DAW [digital audio workstation] that I use to do production and mixing and stuff. I had everything just laid down. And so from there, I tried to put them together like a Tetris thing. And I was like a crazy, crazy guy. I just cut it and pasted it and changed the keys and pitch. It was like a crazy, crazy moment. But I had the idea of this stream of music.

And whenever I was listening, I was hearing a strong theme or a line – of course, I didn’t invent something. It is the progressive thing – you have a theme, you repeat it. So I tried to do that as much as possible, find the way to put everything [in]. All the themes are repeating during the album. And one time it’s the trumpet; one time it’s the vocals; one time it’s guitar and everything put together.

So I remember I was working. I mean, I worked, more of one month just to have the initial idea of something. Because I wanted to present to the guys that – what I had in mind. Maybe it was a mistake! OK, I throw away one month of my life! But I wanted to. And so everybody was saying, “what is Alberto doing? Where’s the music?” They were waiting for me to just send a file to listen to!

And then I did actually. And everybody was really happy! Of course, we changed stuff; we changed it in the pre-production. But then when we went to the studio to record the album, we changed it again! We changed the set list; one song was completely written in the studio. We’re playing with these guys, it’s like this. We can do it! So it’s good.

Yeah. Before we go on into the recording process, just a little bit, you mentioned you were kind of following the classic concept album/rock opera model. It starts here; it goes to there. And I know Greg has mentioned in the publicity [Genesis’] The Lamb [Lies Down on Broadway] and [Yes’ Tales from]Topographic Oceans as the two [of the most] famous or infamous prog albums out there. Can you think of any models from prog history that maybe influenced you or even any that you tried to avoid?

[Laughs] I think so. I mean, I’m a huge fan of Transatlantic! And [The] Whirlwind is one of my favorite albums of all time. So that was that was one of – the ideas where, “oh, OK, they’re repeating this.” I mean, I love Neal [Morse]. He became like, well, not a friend; I know him, I sang with him and I was just a fan and I’m still a fan. But now knowing him, it was magical. I’m a huge, huge fan. So I love that.

But actually, I also listened to The Incident by Porcupine Tree. That’s a little bit more metal thing. But for the ideas, sometimes you can take the ideas.

And actually, I always go back to The Beatles and the Abbey Road medley. Sometimes always something where I have to refresh my ears. So I listen to that. “Oh, they did this in ‘69. I can do something in 2026! So let me try to do something.”

Exactly. All those really resonate with me: Transatlantic was kind of my gateway drug back into prog after some time away. And Abbey Road I’ve loved since I was a kid.

Yeah! And of course, Genesis, of course Yes. There are a lot of incredible concept albums. But yeah, those were “just go in there, just in the background, just to have a listen and to get inspired.”

Well, you learn from the masters, it’s true.

Absolutely, yes, of course.

So I wanted to play kind of a lightning round game with you. And this can be maybe talking about your time in the studio, especially, but also about the rest of the development process. I wanted to ask you your perspective on what each of your bandmates kind of brought to Woodcut that’s special.

[More after the jump . . .]

Continue reading “Big Big Train’s Alberto Bravin: the 2026 Progarchy Interview!”