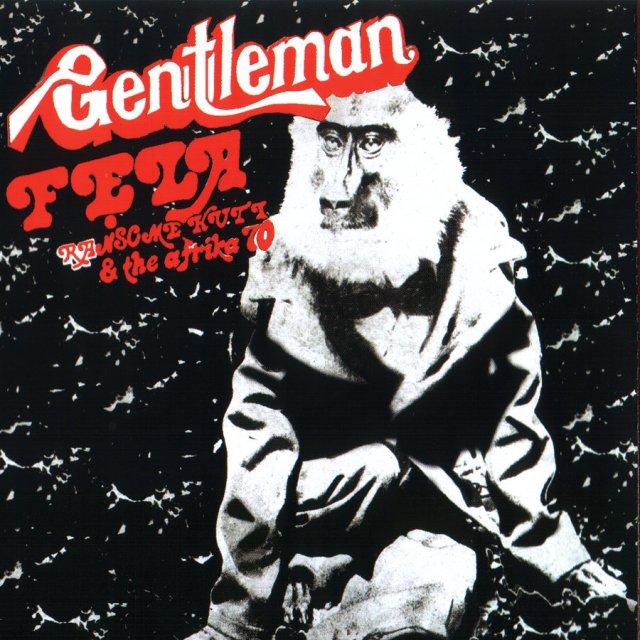

It can look like a conspiracy, from the outside, to know what those of us in middle America grew up with musically in the 1970s. Ensconced deeply in our Yeses and our Styxes and our REO-es and our Kansases, we often missed out on the larger view of the world, despite the delicious depths of what did come delivered over the airwaves. Case in point: Fela Kuti. The Afro beat. I suspect even if you were a jazzbo soldiering on in the post-bop wonderland delivered in the ever-widening sidelong jams of Miles and Herbie and Pharaoh, there might be quite a gulf between such distinctly American cooking and a Nigerian self-trained sax player and polemicist who wielded the conch of Democracy for Africa. Kuti’s mission, though, was a kind of a trojan horse. It looks an awful lot like a super tight big band stomp, epic riffing over a relentless beat, and musically it is. But pulsing underneath was a heat that Kuti, with an outsized personality and voice that all-too-easily drew fire from Nigeria’s governing elite, stoked with an enthusiasm that would eventually enflame his life in tragedy.

It can look like a conspiracy, from the outside, to know what those of us in middle America grew up with musically in the 1970s. Ensconced deeply in our Yeses and our Styxes and our REO-es and our Kansases, we often missed out on the larger view of the world, despite the delicious depths of what did come delivered over the airwaves. Case in point: Fela Kuti. The Afro beat. I suspect even if you were a jazzbo soldiering on in the post-bop wonderland delivered in the ever-widening sidelong jams of Miles and Herbie and Pharaoh, there might be quite a gulf between such distinctly American cooking and a Nigerian self-trained sax player and polemicist who wielded the conch of Democracy for Africa. Kuti’s mission, though, was a kind of a trojan horse. It looks an awful lot like a super tight big band stomp, epic riffing over a relentless beat, and musically it is. But pulsing underneath was a heat that Kuti, with an outsized personality and voice that all-too-easily drew fire from Nigeria’s governing elite, stoked with an enthusiasm that would eventually enflame his life in tragedy.

1973’s “Gentleman” is an early classic, the title track of a record where Kuti ironically declares “I’m not a gentleman at all.” He doesn’t want anything to do with what that word means in a place where the gentlemen were in essence slaveholders. It’s an open statement of discontent, of a desire for justice. And it wouldn’t mean half so much as it does if his band didn’t burn the house down with their playing. It’s here that the idea of world music takes shape, borrowing from blues and jazz structures of the African diaspora and feeding back on them — once you hear Kuti’s work it’s hard to imagine Soft Machine’s Third, krautrock bands like Out of Focus and Embryo, contemporary bands like Seven Impale, and even the greater part of British punk and American rap without it. Kuti’s voice was loud, gruff, a rap that cried its flawed humanity atop a fury of horns and guitars and drums. It’s serious shit and a party all at once. Anger and joy and heartache. Even if that conspiracy was true and the staid worldview of 70s America denied me Kuti, I’m hearing it now. And I am still listening.

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section above.

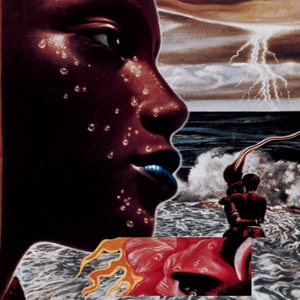

It’s 1975 and I’m nine years old. I’m lying on my back in Reservoir Park, a small city block of grass and oaks next to the University of Utah. In my head is a song that trips and travels as I run and play with friends. It’s a vision of sound, a strong impression of bright sun and moving clouds, a feeling on my skin, a growing chill in the air. Is it October? The song is a constant rhythm of consciousness and motion, a life in itself but also within me, as if I’m one of its many, many tributaries.

It’s 1975 and I’m nine years old. I’m lying on my back in Reservoir Park, a small city block of grass and oaks next to the University of Utah. In my head is a song that trips and travels as I run and play with friends. It’s a vision of sound, a strong impression of bright sun and moving clouds, a feeling on my skin, a growing chill in the air. Is it October? The song is a constant rhythm of consciousness and motion, a life in itself but also within me, as if I’m one of its many, many tributaries. A deep blues, a call to enlightenment, a psychedelic spiritual of epic proportions, Pharaoh Sanders’ “The Creator has a master plan” rings with a disciplined clarity one might expect from a former

A deep blues, a call to enlightenment, a psychedelic spiritual of epic proportions, Pharaoh Sanders’ “The Creator has a master plan” rings with a disciplined clarity one might expect from a former  The art gallery of rock and roll is a rich and welcoming place, with room upon room spinning off into many-directioned distances. There is no entrance fee or warnings to stand back, please, from the piece. And, like at all great museums, any pretense to surface comportment is, if meaningful at all, only a nod of respect to the spark of human creativity. A sign that we don’t stand in willful ignorance. Before the work, within the work, we are all children. It is in rock’s nature to empower its listeners to create, and within this space there is no genre, no boogie no punk no progressive no pop no indie no folk, just an honoring of the empty canvas and the unrestrained fire banked down in humanity. It’s what I love about rock, and it’s what made Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks happen.

The art gallery of rock and roll is a rich and welcoming place, with room upon room spinning off into many-directioned distances. There is no entrance fee or warnings to stand back, please, from the piece. And, like at all great museums, any pretense to surface comportment is, if meaningful at all, only a nod of respect to the spark of human creativity. A sign that we don’t stand in willful ignorance. Before the work, within the work, we are all children. It is in rock’s nature to empower its listeners to create, and within this space there is no genre, no boogie no punk no progressive no pop no indie no folk, just an honoring of the empty canvas and the unrestrained fire banked down in humanity. It’s what I love about rock, and it’s what made Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks happen.

It’s unavoidable. It is impossible to speak of modern music, regardless of genre, and not take note of the critical importance of Miles Davis. Call him what you will or what he called himself — a genius of composition, a dazzling trumpeter/performer and band leader/manipulator, an agent provocateur, a counter-racist, coke fiend, pimp, misogynist — Miles Davis was to musical art what Pablo Picasso was to visual art in the 20th century. It’s so true it’s not even up for debate, and there’s about a kazillion hours of recorded, generous, lovely, dark, funky, bopping proof. By natural extension Davis was the incarnation of what

It’s unavoidable. It is impossible to speak of modern music, regardless of genre, and not take note of the critical importance of Miles Davis. Call him what you will or what he called himself — a genius of composition, a dazzling trumpeter/performer and band leader/manipulator, an agent provocateur, a counter-racist, coke fiend, pimp, misogynist — Miles Davis was to musical art what Pablo Picasso was to visual art in the 20th century. It’s so true it’s not even up for debate, and there’s about a kazillion hours of recorded, generous, lovely, dark, funky, bopping proof. By natural extension Davis was the incarnation of what  If love is one of the most common themes in song, love songs that stretch beyond simple declarations, admitting a type of defeat in the face of defining such an emotion, are remarkably rare. In the past weeks soundstreamsunday has featured

If love is one of the most common themes in song, love songs that stretch beyond simple declarations, admitting a type of defeat in the face of defining such an emotion, are remarkably rare. In the past weeks soundstreamsunday has featured  The Benny Goodman Orchestra’s performance at Carnegie Hall in January 1938 has a place in history as the coming out party for jazz, a legitimizing of an art form within the fortress of American (read: white/European) highbrow music. Ripe for irony? Yes. But when we recall this was the era of “race” records, and that jazz in the white American psyche was still an odd conflation of jump-and-jive black culture, blackface minstrelsy, and the carefully staged musical numbers of Hollywood sophisticates, Goodman and company’s triumph was quite real. Bringing an integrated group of musicians that included the best of its day to Carnegie Hall, blowing the collective Depression-era Jim Crow “high culture” hive-mind…. remarkable. This music is fierce, sometimes nasty, less a nod to propriety than a tuxedo-ed finger in the eye, dashing racial and artistic division by sheer force of celebratory musicality. “Sing Sing Sing,” a Goodman Orchestra signature tune written by Louis Prima, was the band’s finale, clocking in at over 12 minutes, and thus recorded, using the technology of the time, on acetate discs using a relay of multiple turntables (while the concert was almost instantly legendary, the recordings wouldn’t be made available for over a decade: see

The Benny Goodman Orchestra’s performance at Carnegie Hall in January 1938 has a place in history as the coming out party for jazz, a legitimizing of an art form within the fortress of American (read: white/European) highbrow music. Ripe for irony? Yes. But when we recall this was the era of “race” records, and that jazz in the white American psyche was still an odd conflation of jump-and-jive black culture, blackface minstrelsy, and the carefully staged musical numbers of Hollywood sophisticates, Goodman and company’s triumph was quite real. Bringing an integrated group of musicians that included the best of its day to Carnegie Hall, blowing the collective Depression-era Jim Crow “high culture” hive-mind…. remarkable. This music is fierce, sometimes nasty, less a nod to propriety than a tuxedo-ed finger in the eye, dashing racial and artistic division by sheer force of celebratory musicality. “Sing Sing Sing,” a Goodman Orchestra signature tune written by Louis Prima, was the band’s finale, clocking in at over 12 minutes, and thus recorded, using the technology of the time, on acetate discs using a relay of multiple turntables (while the concert was almost instantly legendary, the recordings wouldn’t be made available for over a decade: see