(Note: artist/title listings link to available Spotify playlists.)

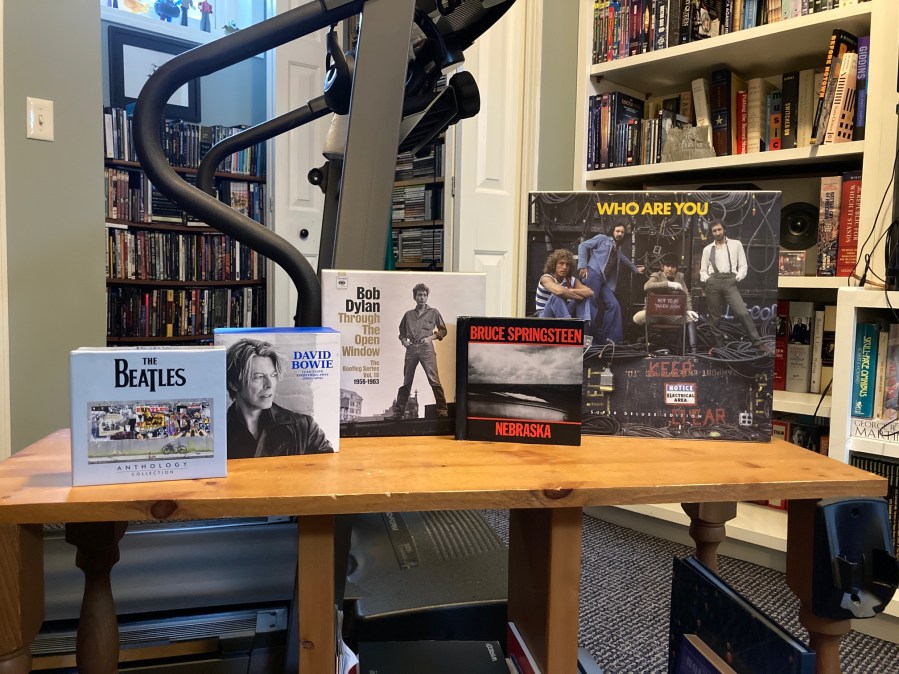

The Beatles, Anthology Collection. George Harrison himself pronounced the original Anthology a bunch of “barrel scrapings” – to which a Beatlemaniac like me could only respond, “Hand me that wooden spoon, would you?” Even back in the 1990s, I enjoyed volume 1 for its scruffy early demos and thrilling on-air performances (before the screaming took over), volume 2 for its glimpses of the Fabs blossoming as recording artists (along with, to be fair, some genuinely dreadful clunkers), and volume 3 for the astonishing homestretch of John, Paul & George’s songwriting that fueled The White Album, Abbey Road and Let It Be. The new Anthology 4 functions as a sped-up reprise of its three big brothers: rougher takes of early classic tunes, shot off in the studio like kids’ fireworks, dominate disc 1, while disc 2 excavates further surprises from the final years: you’ll never hear a more incandescent minute of rock than the proto-speed metal jam on Elvis’ “(You’re So Square) Baby I Don’t Care”! Recent Beatles boxes have seemed more a product of duty than delight on Apple’s part – is their deal with The Disney Channel cramping their style? – and Anthology Collection doesn’t really up their game. But there’s still moment after moment of pure joy here, not least the fresh reworkings of the Threetles’ “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love” right alongside McCartney & Starr’s elegiac “Now and Then”. So now then, can we pleeeeeeeeeeeeeease have that deluxe version of Rubber Soul?

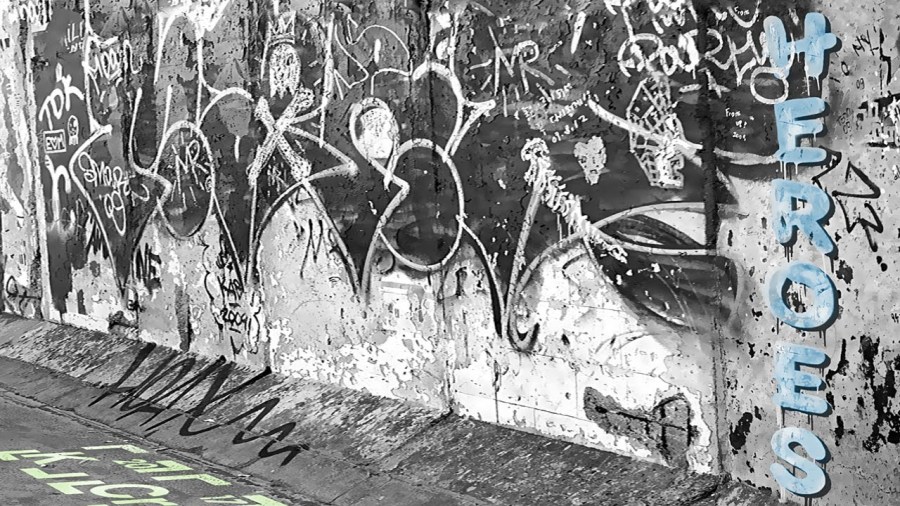

David Bowie, I Can’t Give Everything Away [2001-2016]. Thanks to Cedric Hendrix (the man behind the marvelous blog Cirdec Songs) for flagging this one after I missed it last fall. By the 21st century, Bowie had powered through so many personae – Warholian theatre kid, rock/funk chamelon, hermetic avant-gardist, ravenous fame-chaser; now, it seemed, he had just decided to be himself. His Oughties albums Heathen and Reality, spooky and sleek in turn, were fabulously creative; their supporting tours showcased a Bowie at ease with his entire legacy, backed by an all-star musical entourage. Yet 2013’s The Next Day shook things up again, the music leaning into dark shadows and jagged edges, Bowie posing furious riddles of aging and mortality, veiling the answers in enigma and paradox. Then, one last leap forward: Blackstar, released mere days before Bowie’s death from cancer, a tense, soulful mix of fusion, hip-hop, pop, even a skosh of prog – the singer cutting his vocals live on the studio floor as a fresh quartet of New York jazzers pushed him hard all the way. Plenty of extras from the era here, along with enlightening liner notes and mouthwatering design work on the 13-disc box itself, but the revelation here is Bowie’s final, sustained artistic peak. Through all the changes fueled by his voracious brain, capacious heart, unmistakable croon and impeccable musical skills, the man never stopped reaching for the perfect moment; it’s simply spectacular how often he nails it in this set.

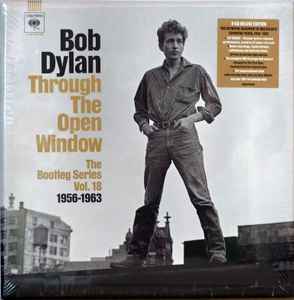

Bob Dylan, Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series Vol. 18, 1958-1963. Whether at Midwestern college parties or in Greenwich Village clubs, the young Bobby Zimmerman hit American folk music like a thunderbolt, making an almighty racket with guitar, harmonica, and that annoying yet oddly compelling voice. This eight-disc set, riding the success of Oscar-nominated biopic A Complete Unknown, showcases both Dylan’s raw ambition and his prodigious artistic growth during his early years; clawing his way to headline gigs and a major-label record deal, drawing inspiration from blues and British folk traditions as his distinctive style takes shape, swept up in the Civil Rights Movement, he resists easy definition all the while. It all culminates in a sold-out Carnegie Hall concert that lays out Dylan’s achievement in full: there’s wickedly gleeful humor (“Talkin’ World War III Blues”, onstage banter aplenty); earnest protest both dated (“With God on Our Side”, “When the Ship Comes In”) and timeless (“Blowin’ in the Wind”, “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, “Masters of War”); stark ballads of loneliness, injustice and vengeance (“Boots of Spanish Leather”, “Seven Curses”, “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”); even a breathtaking paean to the sheer beauty of existence (“Lay Down Your Weary Tune”). Dylan’s reactions to JFK’s assassination and The Beatles’ ascent — moving into pure poetic sound and imagery, bringing it all back home to the rock’n’roll he grew up with by “going electric” — were still ahead, but this collection ably demonstrates both his game-changing impact on the folk subculture and how rapidly he grew beyond it.

Bruce Springsteen, Nebraska ’82: Expanded Edition. Consciously or not, Springsteen traveled Dylan’s path in reverse in the early 1980s. Hot off a triumphant international tour fronting the E Street Band (complete with hit single), The Boss went to ground, recording hushed, minimal home demos that expressed an outsider’s alienation, marinated in American dreams gone sour. These songs lay bare the haunted hearts of hapless, nihilistic outlaws (the title track, “Johnny 99”), family members at unending odds (“Highway Patrolman”, “My Father’s House”), immobilized victims of unspoken hopes (“Mansion on the Hill,” “Reason to Believe”). The new five-disc box ponies up on revealing extras, with additional solo demos (many of which wound up on future Springsteen releases in vastly different form) and wild, punkish full-band studio takes (the howling versions of “Downbound Train” and “Born in the USA” have to be heard to be believed). But, as unpacked in Warren Zanes’ fine 2023 book Deliver Me from Nowhere (the basis for the recent biopic), Nebraska itself resisted ornamentation. Whether in the fresh remaster of its original cassette form or in the BluRay of a 2025 solo performance, Bruce delivers everything these songs need and no more: a lonesome voice, mesmerizingly spare guitar, a few distant instrumental accents, and eerie slapback echo. Another game-changer — the sound of a dark, hallucinatory past, crawling up from underground to claim the singer’s soul.

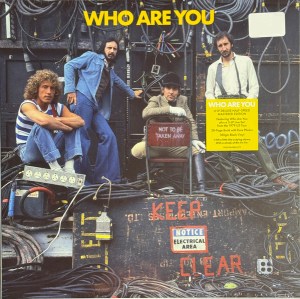

The Who, Who Are You: Super Deluxe Edition. Caught between mid-1970s megastar doldrums and the first onslaught of Britpunk, Pete Townshend once again turned angst into art, a drunken night out in the company of selected Sex Pistols furnishing the lyrical core of his hypnotic title epic. Rallying his bandmates proved Townshend’s main challenge; a debauched Keith Moon had to be threatened with the sack to serve up even flashes of his former brilliance. And then Moon died. The sad circumstances have always colored the reception of Who Are You, but in retrospect it’s a fine album; nobody prays for transcendence as furiously as Townshend, and nobody dances all over life’s problems like The Who. Roger Daltrey defiantly confesses Townshend’s sins and perplexities on “New Song”, “Sister Disco” and “Music Must Change”; John Entwistle undercuts any heavy vibes with his blackly humorous “Trick of the Light”, “905” and “Had Enough” (the latter fiercely declaimed by Daltrey); and new mixes by – who else – Steven Wilson finally level the sonic score, bringing Pete’s blazing power chords right up front with the burbling synth beds and string sections. Demos and sessions, a drums-favoring alternate mix by Glyn Johns, chaotic rehearsals, a ferocious final show with Moon (filmed for classic rockdoc The Kids Are Alright) and a fiery double-disc sampling from the US tour that introduced Kenney Jones on drums are included in the eight-disc box, too.

— Rick Krueger

Forty years on it seems like it must have been inevitable, obvious even, the crossing paths of

Forty years on it seems like it must have been inevitable, obvious even, the crossing paths of