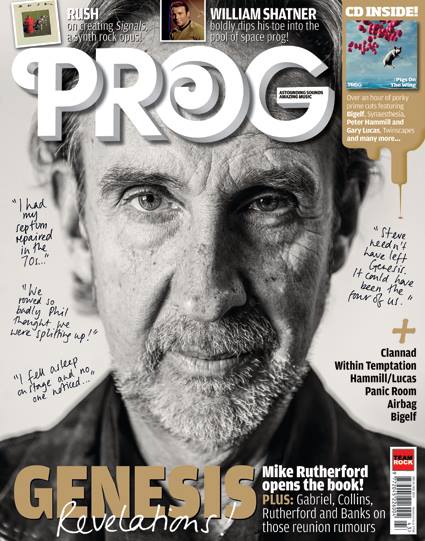

Well, what can we say but, excellent job, Jerry Ewing! This is the best cover yet of any PROG issue thus far. Just look at the immensity of character that radiates from Rutherford’s face: English, Stoic, Creative. I love it.

Tag: Jerry Ewing

Progression Magazine #66

There are many of us at progarchy who love Jerry Ewing and PROG magazine. Sadly, though, it’s very difficult to find issues of it in print here in the U.S. Hastings carries it, but the issues are always two or three issues behind what our British cousins are enjoying. PROG, of course, offers an iPad version, and it’s perfectly fine, except that it lacks the cover mount cd. Still, nothing beats a physical copy of a magazine.

For those of us in North America who crave a tangible, physical prog rock magazine, we have one: Progression. This is only my second issue, and I’m rather shocked I didn’t know about it before issue 65. Better late than never, of course. So, I’m very glad to know of it now, and I want to spread the good news to all progarchy readers.

It has far more print to it than PROG does; indeed, it packs as much print into the magazine as possible. Issue 66 is 112 pages long, and it features a number of strong interviews and insightful, if somewhat short, reviews of current releases. The editor, John Collinge, has done an excellent job, and he should be applauded and supported.

Each issue is $7.95, retail, and it comes out four times a year. For more information, check out the official website:

http://progressionmagazine.com

PROG Magazine Celebrates the Forthcoming Glass Hammer CD

Really nice to see PROG magazine and editor Jerry Ewing giving Glass Hammer their just due! Thank you, PROG.

Jon Davison, who also fronts Yes, has laid down vocal tracks alongside returned live singer Carl Groves and former member Susie Bogdanowicz. Guest musicians include Rob Reed of Magenta, David Ragsdale of Kansas and Randy Jackson of Zebra.

And the album marks Glass Hammer’s first-ever collaboration with an outside lyricist in the track Crowbone, penned by British historical fiction novelist Robert Low.

Babb tells Prog: “We turned a corner last year when Carl rejoined to fill in for Jon, who was touring with what we call ‘the other band.’ We knew it wasn’t a good thing to have Carl only front us on stage, but we’d always said how much we would love to have him in the studio, as well as Susie – so, back she came as well In our minds, they’d never really left.

To keep reading (and you should!), go here: http://www.progrockmag.com/news/glass-hammer-unveil-ode-to-echo/

Steven Wilson: A Minority Report

In almost every way, Steven Wilson is widely regarded as the current leader of progressive rock music. It’s a title he claims he did not seek, does not want, and, in fact, fought against time and time again.

And yet, he is, for all intents and purposes, “Mr. Prog.” “No discussion on progressive rock is complete without mentioning Steven Wilson,” Tushar Menon has recently and rightly claimed at Rolling Stone (June 24, 2012).

Having turned 46 this year [I’m just two months older than Wilson], Wilson has been writing and producing music for over two decades. Best known in North America for his leadership of the band, Porcupine Tree, Wilson came to the attention of the American and Canadian public through the appreciation offered by North American prog acts, Spock’s Beard, Rush, and, most especially, Dream Theater.

In addition to the thirteen studio albums released under the name of Porcupine Tree, Wilson also has played in No-man, Bass Communion, and, most recently, has released three well-received solo album. Last year, he and Swedish progressive metal legend, Mikael Akerfelt, wrote a brooding folk-prog album under the name of “Storm Corrosion.”

He has also leant his talents–for he is one of the finest audiophiles alive [though, I much prefer the talents of a Rob Aubrey]–to re-mixing a number of classic but often forgotten or misunderstood progressive albums from the 1970s and 1980s, including works by Jethro Tull, Yes, XTC, and King Crimson.

Porcupine Tree music is very very simple. There’s nothing complex about it at all. The complexity is in the production. The complexity is in the way the albums are constructed . . . . And that really is why I have to take issue when people describe us as progressive rock. I don’t think we are a progressive rock band.–Steven Wilson, 1999 interview with dprp.net.

Porcupine Tree albums probably cannot be classified, at least not easily. Beginning as somewhat of a satire on psychedelic music, not too far removed from the fake history of XTC’s alternative ego, The Dukes of Stratosphear, Porcupine Tree invented its own history when Wilson first released music under the name. Since then, Porcupine Tree albums have crossed and fused a number of genres, including space rock, impressionist jazz, hard rock, AOR, New Wave, pop, and metal. Wilson has been open about his influences, and he has prominently noted the work of Talk Talk, Tangerine Dream, Pink Floyd, Rush, The Cure, and a whole slew of others.

What Wilson claims to like most is the creating and maintaining of the “album as an art form, [to] treat the album as a musical journey that tells the story,” rejecting the importance of an individual song. “That’s what I’m all about,” he told a reporter for the Chicago Tribune (April 26, 2010).

In hindsight, he believes that his fear of being labeled “progressive” was simply a fear of being associated with those he considers the wrong type of people (interview with Dave Baird, dprp.net, June 2012)

And, yet, almost and anyone connected in any way with the progressive rock world would immediately identify Wilson as its most prominent face and voice. One insightful English fan of the genre, Lisa Mallen, stated unequivocally, “Steven Wilson is THE most highly regarded person working in the prog industry right now.” Though a long time devotee of progressive rock, Mallen has only recently started listening to Wilson’s music. Wilson is also shaping and defining music in a way that probably only Neil Peart could and did for a generation coming of age in the late 1970s and 1980s. A graduate student in the geographic sciences in Belgium as well as a musician, Nicolas Dewulf, writes, “Steven made me appreciate music in a totally different way, as an art form.” Another long-time prog aficionado, serious thinker, and prolific reader, Swede Tobbe Janson (and fellow progarchist) writes, “I respect SW for being very serious about this wonderful thing called music.” Still, with a mischievous Scandinavian twinkle in his eye, Janson asks, Wilson “is fascinating but sometimes I can wonder: where’s the humour?”

Most recently, Wilson has claimed the golden age of rock music to be 1967 to 1977, the years during which rock realized it could be an art form as high as jazz and classical but before the reactionaries of punk gained an audience through their simple, untrained, and unrestrained anger. “I was born in ’67/The year of Sergeant Pepper and Are You Experienced? It was a suburb of heaven,” Wilson sings in 2009’s “Time Flies.” Wilson’s dates are probably more symbolic than literal. For example, he cites “Pet Sounds” (1966) and “Hemispheres” (1978) as essential albums in rock.

For his part, Wilson believes it critical to maintain his independence as much as possible. “The moment you have a fan base, is the moment you start to lose a little bit of your freedom. The greatest thing of all is to make music without having a fan base because [it’s] the most pure form of creation.” (interview with Menon, Rolling Stone India, June 24, 2102) Reading Wilson’s words, it’s difficult not to think of a younger Neil Peart writing the lyrics of Anthem (1975). As Wilson recently told Menon, “For me, it’s still about being very selfish and doing what I want to do.”

Wilson even refuses to read reviews of his music, and he asks those around him (including his manager) not even to hint to him what been written, good or bad. Wilson admits to becoming just as upset by good reviews as by bad, as he thinks even the good reviewers rarely understand him. With the good reviews, Wilson especially despises when the reviewer “compare[s] you to somebody that you don’t like.” Further, Wilson claims, he’s a “kind of idiot-savant” and “I think I’m incapable of making records [ ] for anyone else than myself.” (interview with Dave Baird, dprp.net, June 2012).

Wilson has proclaimed repeatedly that he is a “control freak,” and, frankly, it would be difficult for anyone to listen to any of his music without realizing the perfectionist side of him immediately. It’s one of the greatest joys of listening to his music. It’s never flawed in anyway. Indeed, if there is a flaw in Wilson’s music, it comes with fatigue of immersing oneself in such perfection.

As Canadian classical philosopher and fellow progarchist, Chris Morrissey, has so aptly described it, “His use of 5.1 mixes perhaps shows us the way forward for prog’s future. The beauty and complexity of prog music seems to demand the sort of treatment that Steven Wilson has shown us it deserves.”

None of this, however, should suggest that Wilson is without his critics. An American mathematician and highly-skilled artist of wood and glass, Thaddeus Wert (another progarchist!), offers an appreciative but equally objective appraisal of Wilson’s works: he “seduces the listener with beautiful music, but there is often an undercurrent of menace and despair in his lyrics that can be disturbing.”

Wert is correct. One of the most jarring aspects of any Steven Wilson song is its gorgeous construction on top of very dark subjects and lyrics. In interviews, he claims to give as much attention and detail to his lyrics as he does to the beauty and perfection of the music. “I try to make the lyrics have some depth, yes, I mean I don’t want the lyrics to be trivial” (interview with Brent Mital, Facebook Exclusive, April 28, 2010). His lyrics deal with drug (illicit and prescription) use, cults, the banality of modernity, commercialism (Wilson believes “Thatcherism” accelerated the western drive toward hollow materialism), serial killing, death in an automobile, and mass conformity.

Widely regarded as his best work, Porcupine Tree’s 2007 “Fear of a Blank Planet” offers one of the most interesting critiques of modern and post-modern culture in the world of art today. Based on Bret Easton Ellis’s novel, Lunar Park, the album explores the banal world of the “terminally bored” and features the disturbing front cover of a teenager, zombified by the glow of the T.V. Screen. Wilson’s album is effective and artful social criticism of the best kind. Even the EP released shortly after Fear of a Blank Planet, “Nil Recurring” offers some of the most interesting rock music ever produced.

Outside of being labeled and “forced” to conform to the expectations of fans, Wilson’s greatest fear comes from the irrationality and demands of religious belief, as he sees it. In his lyrics and in interviews, Wilson speaks at length about his opposition to religion. “Anything to do with organized religion really makes me really f***in’ angry.” Even non-cultish ones are “living a lie, but, you know, ok, if it makes them happy, that’s fine” (Interview with Mital, FB Exclusive, April 28, 2010). One can probably safely assume that Wilson has never read Augustine, Aquinas, More, Bellermine, or Chesterton. Would they still appear so bloody stupid if he had?

Usually far more articulate than this, Wilson expresses his greatest Bono-esque opposition to televangelists who use faith to create power and promote self-aggrandizement. In the same interview, Wilson states that Christians of all kinds must find the need to divorce his lyrics from his music if they’re to appreciate his work. “I’m sure we have fans that are Christians and . . . . [in original] I know we do, you know. That’s not something lyrically I think they could ever find sympathy with or I could, but musically they must love the music” (Interview with Mital, FB Exclusive, April 28, 2010).

Wilson’s most blatant statement of skepticism comes from the video for a single from his Storm Corrosion album, “Drag Ropes.” Stunningly beautiful and haunting gothic folk prog–akin to some of the earliest work of The Cure–drones, while stained glass images of Tim Burton-eque creatures defy the Catholic Church and embrace some form of paganism. A Catholic priest, under the bloody image of a Crucifix, laughs diabolically as a pagan is dragged to the gallows. Paradoxically, not only is the art and animation of the video utterly dependent upon the iconography of the Christian tradition, but the music also carries with it an intense if elegiac and funerary high-church quality.

Whether Wilson recognizes this explicitly or not, he’s correct about what a Christian might find appealing about his music. Whether he’s writing a solo work or working in Porcupine Tree, No-man, or Storm Corrosion, his music exudes the liturgical despite what genre he employs on any given song or album. Consciously or not, it’s almost certainly one of the qualities that most draws listeners to Wilson’s vast corpus of work. Liturgy predates Christianity, of course. It dates back to the public performances of the polis of ancient Greece, a way to incorporate all through art and performance into a community. Every person–no matter his or her race, ethnicity, or religious (or lack thereof)–desires to be a part of such a thing. It’s worth remembering that we define a sociopath precisely as this because he or she refuses to be a part of community.

As is clear from the Storm Corrosion video, Wilson does not understand the mass of Christians (at least Catholic and Eastern Orthodox ones) and their desires or their serious failings. In this, he’s not much different from the rest of the modern world, and probably few serious Christians will get upset with the attempt to upset them. Christians have endured far, far worse than Wilson’s video, and, of course, sadly, they’ve dealt out far worse than the priest of Storm Corrosion’s imagination.

Theology aside, if there’s one essential thing missing in Wilson’s art, it’s his inability to present something in a truly organic form. One sees this most readily when comparing his work to that of other progressive greats (though, to be fair (well, honest) to Wilson, he’s claimed that there really is no competition within progressive rock; of course, he’s completely wrong). His most Talk Talk-eque song, for example, is his two-minute “The Yellow Windows of the Evening Train” (2009). In almost every way, with one vital exception, it could have appeared on Talk Talk’s 1991 masterpiece, “Laughing Stock.” Porcupine Tree’s most Rush-eque song is the 17-minute masterpiece, “Anestheize” (2007). Each song, though, remains an abstraction, a stunning mimicry. As great as each song is, each is missing the very soul that made Talk Talk and makes Rush so good. And, this despite the fact that Rush’s Alex Lifeson performs the guitar solo on “Anethetize.” It might, interestingly enough, be Lifeson’s best solo, ever.

Compared to other prog greats of this generation, Wilson’s music seems impoverished. Not because it’s not great, but because it lacks a sense of the human and of the humane. Even at his best, Wilson remains abstract and disconnected. When one hears the music of much of the last two decades, one feels the very depth of the soul and being that each of these groups/artists brings to the art. Five minutes of listening to Big Big Train, Matt Stevens, The Tangent, or Cosmograf makes me realize how human and humane these artists are. They give their very selves to their art. Listening to Wilson, as much as I appreciate the precision put into the music, the lyrics, and, especially, the audio quality, I can’t help but think he’s reading a treatise from the most rational person of the 18th century. Where are the kids? Where are the relationships? Where are the foibles? Where is the greatness?

What hit me hardest came not with Storm Corrosion, with its blatant anti-Christian posturing, but with Wilson’s third solo album, The Raven That Refused to Sing, released this year.

From Jerry Ewing to Greg Spawton to Harry Blackburn to Richard Thresh to Anne-Catherine de Froidmont to a number of other folks I respect immensely, The Raven has received almost nothing but praise.

For me, though, it’s almost 55 minutes of parody—cold, perfect, distant, abstract. From the opening few lines and minutes of the album, I thought, “This is simply Andy Tillison’s work without the humor, the warmth, the depth, the breadth, or the sharp-witted intelligence.” I thought this on my first listen, and I thought this on my most recent listen (today). I certainly don’t want to put Tillison in a bad spot, and I don’t want to praise one while knocking down the other. But, the comparison between Wilson and Tillison, I think, is a fair one. Listen to the 55 minutes of The Raven (2013) and the 60 minutes of The World That We Drive Through (2004). While it’s not a note for note similarity, it’s clear that Wilson has found his style (compare The Raven to his first two solo albums) in what Tillison has so wonderfully cultivated over the last decade.

I have absolutely nothing against honoring or borrowing from the greats. But, it does rankle a bit thinking about the genius who has spent most of his career separating himself from his brethren while the thinking of the other genius who has struggled so seriously in the very name of his brethren.

Honor should go where honor should go. Really, who deserves to be Mr. Prog?

Please don’t get me wrong. I’m a fan of Steven Wilson. I own everything he’s produced (even the more obscure stuff from early in his career), and I almost certainly will continue to do so. But, his own self-admitted quirks will always keep me at a distance. And, from what I’ve read from him, he’s perfectly fine with this. In fact, he’ll almost certainly never even know this article existed.

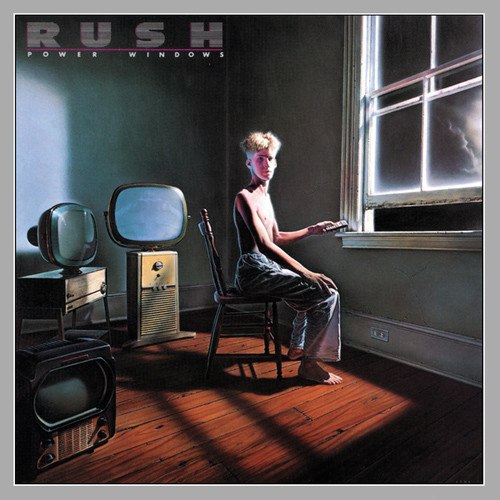

Power Windows: Rush and Excellence against Conformity

It’s the power and the glory

It’s a war in paradise

It’s a cinderella story

On the tumble of the dice

—Neil Peart, “The Big Money,” 1985

***

Power Money

It would have been impossible to avoid Power Windows in the Fall of 1985, I being a senior in a Kansas high school, even if I had wanted to.

And, I didn’t.

Every where I turned that fall—in ways far more than any other Rush song since Tom Sawyer—I heard “The Big Money.” MTV played the video repeatedly (we didn’t have MTV, but friends did), and our wonderful local radio station—KICT95 out of Wichita—had it in constant rotation. Of course, being a massively obsessed Rush fan since first encountering them in 7th grade detention, I was thrilled to see Rush get so much attention.

Sadly, though, I became overly saturated with “The Big Money.” It’s the only Rush song that has ever grown tiring for me. For years, it stood up there with “Stairway to Heaven.” I just shut both out of my mind, flipped the radio dial when either played. As Power Windows is one of my all-time favorite albums, this has been rather difficult for me to accomplish. For nearly two decades, though, I merely started the album with the second track, “Grand Designs.”

Then, on September 18, 2012, at the Palace in Auburn Hills, Michigan, standing next to my good friend, Dom, Rush played it as the second track of the Clockwork Angels tour. Straight from Subdivisions to The Big Money to Force Ten and then, three songs from Power Windows in a row: Grand Designs; Middletown Dreams; and Territories. Half of the album! Freaking brilliant. Poor Dom. He’s only a college student, and he had to hear my sound byte reminiscences for every track. I was reliving a huge part of my high school experience.

Seeing “The Big Money” live made me realize why that song is so wonderful. Alex, Geddy, and Neil brought immense energy to it (and Force Ten, as well—the most rocking version I’d heard from Rush; Alex even played one of his best guitar solos for this song on this tour). Suddenly, whatever tiredness and reluctance I’d felt about “The Big Money” over the last several decades dissipated at the moment the opening few notes began. Add video of spinning and printing dollars as well as the Three Stooges, and I was sold. (Sorry, bad choice of words). But, really, everything was perfect—the drumming, the bass, the guitar solo. And, of course, the Austin Powers moment at the end: “One million dollars!”

Now, as of the end of 2013, I’m back in and with those autumn days of 1985. Let “The Big Money” reign. I’ve also re-discovered my love of Led Zeppelin 4.

But, the point of the post is not to praise “The Big Money” specifically, but to remember Power Windows. I’m happy to praise both! And, frankly, I’ve been offering praise of Power Windows since it came out, but only with the caveat that The Big Money is a weak point. Now, in 2013, I realize how wrong I was. The whole thing deserves praise, and one cannot separate any song from the whole. It is what it is, and it’s a thing of immense beauty.

Power Jazz

In Contents Under Pressure (by Martin Popoff), Neil argues that he sees Power Windows and Hold Your Fire as two sides of the same coin, separate from Grace Under Press, but also from Presto. Certainly, there’s an argument to be made here. In terms of bass and drums, Power Windows and Hold Your Fire, have the most distinctly jazz feel of any Rush albums. At times, taking the rhythm section alone, the listener might be enjoying a Chick Corea album from the same time period. In production, though, Power Windows comes across as rather raw power, while Hold Your Fire feels rather lush. Whatever similarities—and they are many—the albums seem very different to the listener. Again, as Neil states, the first is an extrovert, while the second an introvert.

As a fan, though, I tend to hear consistent themes in Moving Pictures through Hold Your Fire. Moving Pictures stresses the need to be an individual against the crowd; Signals warns that being such an individual will cause pain, but is worth it; Grace Under Press deals with recovery from such persecution (sometimes in the hallway, sometimes in the concentration camp); Power Windows deals with excellence against conformity; and Hold Your Fire pleads for restraint in the now comfortable individual looking at those he’s made uncomfortable.

Granted, these themes are, for me, autobiographical, in the sense that I grew up with them, and each album plays a key role in my own understanding of the world. That is, these themes might not have been intended by Peart, and, admittedly, perhaps I’m alone in seeing them this way. As I’ve mentioned before, Neil Peart has influenced me as much as anyone in my life—ranging from Plato (I teach western civ for a living, so allow me a little pretense here) to St. Paul to my mother. Plato-Paul-Peart!!! The three Ps.

For me:

- Moving Pictures: 7th Grade

- Signals: 9th Grade

- Grace Under Pressure: 11th (Junior) Grade

- Power Windows: 12th (Senior) Grade

- Hold Your Fire: sophomore year of college.

In terms of wordplay and poetry, Neil is at his best on Power Windows.

In The Big Money, Peart considers the good and the evils of what we now refer quite commonly as “Crony Captialism.” As with much of this album, the shadow of cultural critic, socialist-turned-libertarian and anti-war novelist, John Dos Passos, hangs over The Big Money. Dos Passos also called his style “The Camera Eye.” 1936’s The Big Money concluded Dos Passos’s famous U.S.A. Trilogy. Much like Peart, Dos Passos traveled incessantly, offering a fine cultural criticism over everything he surveyed.

Grand Designs, track two, comes from the final part of the “District of Columbia,” trilogy published by Dos Passos in 1949. It examines individual genius in line with nature and against nature. In the conflict of style and substance, Peart is also referencing the grand Anglo-American poet, T.S. Eliot, and his 1925 poem, The Hollow Men.

The third track, Manhattan Project, anticipates the history-telling prog of Big Big Train, offering a rather neutral analysis of the development of the first three atomic bombs. Interestingly enough for Peart, he continues to harken back to religious language and themes, specially Catholic, referring again and again to “a world without end.”

Marathon echoes a number of other Peart songs, but it does it with extraordinary energy. A celebration of the battle of the Athenians over the Persians in the Fifth Century, BC, it also, of course, deals with the virtue of fortitude.

Territories offers a scathing criticism of propaganda, nationalisms, and nation states. In his criticisms and in the clever examples, Peart echoes the anti-statism of Mark Twain.

Taken, most likely, from the famous 1925 sociological report of Muncie, Indiana, entitled Middletown. Not surprisingly, given the state of sociology in the 1920s, the report considers the every day habits and desires of rural Americans. In his own Middletown, Peart examines the life of rural America as well as the dreams of those wishing to escape, generally unfulfilled.

Emotion Decter is one of Peart’s most Stoic songs, offering something against both the extremes of optimism and the cynicism of despair. In the end, in a common Peart theme, man must restrain his reaction toward others, recognizing that one does not need approval of another should integrity already exist in the original act. A true man judges himself.

The final and most proggish/artistic song of the album is Mystic Rhythms. Rush ends with wonder at the intense diversity of the world and of all of the universe.

Power New Wave

Finding a producer for Power Windows proved difficult at first. After replacing the long-lived Terry Brown (every album up through Signals) with Peter Henderson (Grace Under Pressure), Rush found their third producer in Peter Collins, best known for his work with Nik Kershaw and Blancmange. Making the connection to Britain even stronger, Rush recorded much of the album at Abbey Road Studios and in parts of London. They also worked with Anne Dudley of the Art of Noise, who directed the strings.

Though Power Windows rocks with full force throughout almost all of the album (the final track, Mystic Rhythms, being the very proggy standout), it has also a strange New Wave feel to it. Ok, this needs explaining. Neil and Geddy sound as though they’re playing in a rocking jazz band from the 1980s, but Alex sounds as though he could be playing for The Fixx. Alex, like Jamie West-Oram, seems to be creating immense but punctuated guitarscapes. One of the things that makes Power Windows so effective, is this strange but powerful synthesis of jazz bass and drums with New Wave guitar. In ways that Drama (some of the same production crew worked on both) attempted to be for Yes in 1980, Power Windows succeeds at bridging prog, rock, New Wave, and jazz. I think Drama is a fine album (in fact, a favorite), but I think that Power Windows is truly successful at this attempt to bridge genres. Perhaps, of course, Power Windows couldn’t have come about without Drama first—but an exploration of this would be well beyond the intent of this post.

Suffice it say, I love both.

Power Sources:

- Martin Popoff, Contents Under Pressure (2004).

- Jerry Ewing, ed., Prog #35, Special Edition (April 2013).

- Neil Peart, Roadshow (2006).

- Power Windows liner notes (1985).

- Jim Berti and Durrell Bowman, Rush and Philosophy (2011). This book includes an essay by the brilliant economist (and philosopher), Steve Horwitz.

The Big Big Tangent

Subtitle: “Or, How Plato Made Me Realize We Need to Love 2013. And, If We Don’t, Why We’re Idiots.”

A week or so ago, I had the opportunity to list my top 9 of 11 albums of the past 11 months. Several other progarchists have as well, and I’ve thoroughly enjoyed looking at their lists as well as reading the reasons why the lists are what they are. I really, really like the other progarchists. And, of course, I’d be a fool not to. Amazing writers and thinkers and critics, all.

I’ve been a bit surprised, frankly, that there hasn’t been more overlap in the lists. I don’t mean this in the sense that I expect conformity. Far from it. We took the name progarchists—complete with the angry and brazen red anarchy sign in the middle—for a reason. We’re a free community—free speech, free minds, free citizenship, and free souls. We have no NSA, CIA, or IRS. Nor would we ever want any of these. And, we’ve really no formal rules. We just want to write as well as we can about what we love as much as we love. Any contributor to progarchy is free to post as often or as infrequently as so desired, and the same is true with the length of each post.

I, as well as many others, regard 2013 as the best year of prog in a very, very long time, perhaps the best year ever. I know that some (well, one in particular—a novelist, an Englishman, and a software developer/code guy; but why name names!) might think this is hyperbole. But, having listened to prog and music associated with prog for almost four decades of my four and one-half decades of life, I think I might be entitled to a little meta-ness. And, maybe to a bit of hyperbole. But, no, I actually believe it. This has been the best year in the history of prog. This doesn’t mean that 2012 wasn’t astounding or that 1972 was less astounding than it actually was. Being a historian and somewhat taken with the idea of tradition, continuity, and change, I can’t but help recognize that the greatness of 2013 could never have existed without the greatness of, say, 1972, 1973, 1988, or 1994.

In my previous posts regarding 2013, I thanked a number of folks, praised a number of folks, and listed some amazing, astounding, music—all of which, I’m sure I will continue to listen to for year to come, the good Lord willing. And, I’m sure in five years, a release such as Desolation Rose might take on new meaning. Perhaps it will be the end of an era for Swedish prog or, even, the beginning of an era for the Flower Kings. Time will tell.

So, what a blessing it has been to listen to such fine music. My nine of 11 included, in no order, Cosmograf, The Flower Kings, Ayreon, Leah, Kingbathmat, The Fierce and the Dead, Fractal Mirror, Days Between Stations, and Nosound.

And, there’s still so much to think about for 2013. What about Sam Healy (SAND), Mike Kershaw, Haken, Francisco Rafert, Ollocs,and Sky Architects? Brilliant overload, and I very much look forward to the immersion that awaits.

No one will be shocked by my final 2 of the 11 that have yet to be mentioned. If you’ve looked at all at progarchy, you know that I can’t say negative things about either of these bands . . . or of Rush or of Talk Talk. Granted, I’m smitten. But, I hope you’ll agree that I’m smitten for some very specific and justified reasons. That is, please don’t dismiss the following, just because I’ve praised them beyond what any reasonable Stoic with any real self respect would expect. No restraint with these two, however. Admittedly.

So, let me make my huge, huge claim. The following two releases are not just great for 2013, they are all-time great, great for prog, great for rock, great for music. In his under appreciated book, NOT AS GOOD AS THE BOOK, Andy Tillison offers a very interesting take on the current movement (3rd wave) of progressive rock.

The current, or third wave of new progressive rock bands is as interesting for demographic and social reasons as much as for its music . . . . Suddenly a wave of people in their late thirties began to form progressive rock bands, which in itself is interesting because new bands are formed by younger people. . . .

I’m not sure how much I agree with Andy regarding this. I’m also not sure I disagree. I just know that I’ve always judged eras or periods by what releases seem to have best represented those eras. Highly subjective, highly personal, and highly confessional, I admit. But, I can’t escape it. For me, there have been roughly four periods: the period around Close to the Edge and Selling England by the Pound; the period around The Colour of Spring, Spirit of Eden, and Laughing Stock; a little bit longer—or more stretched out—period around Brave, The Light, Space Revolver; and Lex Rex.

Of course, I’ve only listed three. We’re passing through the fourth as I type this. Indeed, the fourth is coming from my speakers as I type this. Over the last year and a half some extraordinary (I’m trying to use this word in its purest sense) things have happened, all in England and around, apparently, some kind of conflicted twins.

When asked about why he participated in latest release from The Tangent, Big Big Train’s singer, David Longdon, replied:

Amusingly, [Tillison] has said that The Tangent is Big Big Train’s evil twin.

In this annus mirabilis, does this mean we have to choose the good and the evil? Plato (sorry; I’m not trying to be pretentious, but I did just finish my 15th year of teaching western civilization to first-year college students. And, I like Plato.) helped define the virtue of prudence: the ability to discern good from evil.

Well, thank the Celestial King of the Platonic Realm of the Eternal Good, True, and Beautiful, we get both, and we don’t have to feel guilty or go to Confession.

Aside from being the Cain and Abel of prog, The Tangent and Big Big Train offer the overall music world three vital things and always in abundance of quality.

First, each group is smart, intelligent, and insightful. Neither group panders. The music is fresh, the lyrics insightful—every aspect is full of mystery and awe. The listener comes away dazzled, intrigued, curious, and satisfied, all at the same time.

Second, each group strives for excellence in every aspect of the release—from the writing, to the performing, to the engineering, to the mastering, to the packaging. And, equally important, to interaction with fans. Who doesn’t expect an encouraging word and some interesting insight on art, history, and politics—always with integrity—from either band?

As maybe point 2.5 or, at least, the culmination of the first two points, each band has the confidence to embrace the label of prog and to embrace the inheritance it entails without being encumbered by it.

As maybe point 2.5 or, at least, the culmination of the first two points, each band has the confidence to embrace the label of prog and to embrace the inheritance it entails without being encumbered by it.

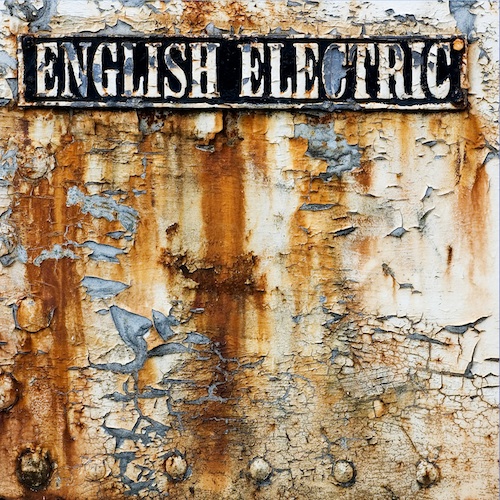

In Big Big Train’s English Electric Full Power, there are hints of Genesis and, equally, hints of The Colour of Spring and Spirit of Eden. But, of course, in the end, it’s always Greg, Andy, David, Dave, Danny, Nick, and Rob.

In The Tangent’s Le Sacre du Travail, there are obvious references as well as hints to Moving Pictures, The Sound of Music, and The Final Cut. But, of course, in the end, it’s always mostly Andy.

Regardless, each gives us what David Elliott masterfully calls “Bloody Prog™” and does so without hesitation. Indeed, each offers it without embarrassment or diversion, but with solidity of soul and mind.

Finally, but intimately related to the first two, each band releases things not with the expectation of conformity or uniformity or propaganda, but with full-blown art. Each band loves the art for the sake of the art, while never failing to recognize that art must have a context and an audience. Not to pander to, of course, but to meet, to leaven.

Life is simply too short not to praise where praise is due. Life is too short to ignore the beauty in front of us. And, no matter how dreary this world of insanities, of blood thirsty ideologies, of vague nihilisms, and of corporate cronyism, let us—with Plato—love what we ought to love.

The Tangent and Big Big Train have given us art not just for the immediate consumption of it, or for the year, 2013,—but for a generation and, if so worthy, for several generations, perhaps uncounted because uncountable.

[Ed. note–if there are any typos in this post, I apologize. I’ve been grading finals, and I’ve been holding my two-year old daughter on my lap. She’s a bit more into Barney than Tillison or Spawton at this point.]

Prog Magazine Reader Poll, 2013

Jerry Ewing, everyone’s favorite Prog editor, has just announced the 2013 Reader Poll. Please take the time to vote as soon as possible.

Jerry Ewing, everyone’s favorite Prog editor, has just announced the 2013 Reader Poll. Please take the time to vote as soon as possible.

I must admit, I’m far more excited to vote for this than I was either for the 2013 local elections or the 2012 national (here in the U.S.) elections. I’d be pretty happy to have Greg Spawton as my mayor or my president.

http://www.progrockmag.com/news/vote-now-in-the-prog-readers-poll-for-2013/

Perfecting Perfection: Big Big Train’s English Electric Full Power

Set in stone. Chiseled, carved, done. Or, at the very least, set in digital stone.

For the ever-growing number of Big Big Train devotees (now, called “Passengers” at the official Facebook BBT page, administered by everyone’s most huggable rugged handsome non-axe wielding, non-berserker Viking, Tobbe Janson), questions have been raised and discussed as to how BBT might successfully combine and meld English Electric 1 with 2 plus add 4 new songs.

How would they do it with what they’re calling English Electric Full Power? Would they make it all more of a story? Would the album become a full-blown concept with this final version? Where might Uncle Jack, his dog, or the curator stand at the end of the album? Actually, where do they stand in eternity?

The members of BBT have already stated that EE as a whole calls to mind–at least with a minimum of interpretation–the dignity of labor. Would the new ordering and the four new songs augment or detract from this noble theme?

Somewhat presumptuously, many of us Passengers proposed what we believed should be the track order, and I even took it upon myself to email Greg last spring with a list. Well, I am from Kansas, and we’re not known for being timid–look at that freak, Carrie Nation, who dedicated her life to hacking kegs and stills to bits, or to that well-intentioned but dehumanizing terrorist, John Brown, who cut the heads off of unsuspecting German immigrants.

And, then, there’s the fact, for those who know me, that I can produce track lists like I can produce kids. No planning and lots and lots of results.

Or, that other pesky fact, that I’m so far into BBT that I could never even pretend objectivity. [Or, as one angry young man wrote to me after I praised The Tangent, “your head is so far up Andy’s @ss, you can’t even see sunlight.” Cool!; who wants to spend tons of time writing and thinking about things one doesn’t like? Not me! As Plato said, love what you love and hate what you hate, and be willing to state both. Guess what? I love BBT and The Tangent! And, just for the record, I’ve never even met Andy in person, so what was suggested is simply physically impossible.]

Admittedly, maybe I’m such such a fanboy that I’ve gone past subjective and into some kind of bizarre objectivity. You know, in the way Coleridge was so heretical that he approached orthodoxy. Or, maybe I’m just hoping that Greg and Co. will ask me to write the retrospective liner notes for the 20th anniversary release of EE Full Power. I’ll only be 66 then. Who knows? Even if I’m in the happy hunting grounds (I’m REALLY presuming now), I could ask the leader for some earth time. . . .

If you’ve read my bloviations this far, and you’re still interested in my thoughts on English Electric Full Volume, well, God bless you. A real editor would have removed the above rather quickly.

Back from the Blessed Isles of soulful prog realms. . . .

In my reviews of English Electric 1 and 2, I stated that these albums were the height of prog music perfection, the Selling England By the Pound of our day. I wouldn’t hesitate to proclaim this again and, perhaps, even more vocally and with more descriptives.

At the risk of turning off some of my friends, I would say that EEFP is even superior to its 1973 counterpart. How could it not be, really? Selling England is now an intimate and vital part of the prog and the rock music traditions, and it has been for forty years. Add that album and hundreds of others to the integrity, dedication,and purposeful intelligence, imagination, and talents of Greg Spawton, David Longdon, Andy Poole, Dave Gregory, Nick d’Virgilio, Danny Manners, and Rob Aubrey. Putting all of this together, well, of course, you’d demand genius.

You’d expect genius.

And, you’d be correct.

It’s the height of justice that Jerry Ewing of PROG awarded Big Big Train with the Prog Magazine Breakthrough Award.

That breakthrough started with that meaningful paean to British and western patriotism in Gathering Speed, reached toward sublime spheres in The Difference Machine, found a form of edenic Edenic perfection in The Underfall Yard and Far Skies (it’s hard for me to separate these two albums for some reason), and then embraced transcendent perfection in English Electric 1 and 2. Each member who has joined the original Greg and Andy has only added to the latest albums. Nick, the perfectionist drummer; Dave, the perfectionist guitarist; Danny, the perfectionist keyboardist; Rob, the audiophile. And by perfectionist, I don’t mean it in its modern usage, as without flaw, but rather as each having reached his purpose.

I don’t think this point can be stressed enough: these guys are perfectionist NOT against each other but with, around, near, above, and below each other. They are a unit of playful perfectionist individuals who become MORE individual, not less, in their community.

Looking at the history of art from even a quasi-detached and objective viewpoint, I think we all have to admit, this is more than a bit unusual.

Breakthrough, indeed, Mr. Ewing. Breakthrough, indeed.

Greg and Andy don’t become less Greg and Andy as the band grows beyond what they have founded, they become more Greg and more Andy. In the first and second wave of prog, how many bands are known for only getting better and better with each album? Those that did are certainly the exceptions. One of the most important differences of this third wave of prog is that the best only get better, even after twenty years of playing. Exhaustion and writers-block seem to be of another era.

BBT exemplifies this trend of improvement in this movement we now call the third wave of prog. And, not surprisingly, when BBT asks artists to guest with them, they invite those with similar trajectories–Andy Tillison and Robin Armstrong to name the most obvious.

Longdon

Again, if you’ve made it this far in this review, you should be asking–hey, Birzer left out David Longdon above, what the schnikees?

Yes, I did. So, let me now praise famous Davids (with apologies to Sirach). I’ve not been shy in past writings (well, over the last four years) to note that I believe David is the finest singer in the rock world at the moment. He has some rather stiff competition, of course, and I reject the notion that he sounds just like “Phil Collins.”

No, David is his own man and his own singer. I do love and appreciate the quality of David’s tone and voice. He possesses a beautiful and talented natural one, to be sure. Nature or God (pick your theology) gave this to David in abundance, and he’s used his own drive and tenacity to bring his voice to the height of his profession.

But, what I love most about David is that he means every single thing he sings. These aren’t “Yeah, baby, let’s do it” lyrics. These are the lyrics of a bard (Greg’s lyrics are just as excellent, of course, as I’ve noted in a number of other articles; these are two of my favorite lyricists of the rock era–rivaling even Mark Hollis).

Longdon can make me as happy as one of my kids running to the playground on the first day the snow thaws (“Let’s Make Some Noise”); he can make me want to beat the living snot out of a child abuser (“ABoy in Darkness”); and he can make me want to start a novena for a butterfly curator.

In no small part, Longdon has a voice that makes me want to trust and follow him.

Put David and Greg together, and their lyrical abilities really knows no known bounds. They are the best writing team, to me, in the last fifty years. I know most would pick Lennon/McCartney, but I’m a firm believer that “electrical storms moving out to sea” trump “I am the walrus.”

EEFP

So, what about this third manifestation of English Electric, English Electric Full Power? Well, all I can state with some paradoxical certainty, Spawton, Longdon, and five others, have now shown it is possible to perfect perfection. I’ll use perfect here in its proper sense: not as without flaw (though that would apply as well) but as having reached its ultimate purpose, as I noted above.

EEFP is still very much about the dignity of labor, and, as such, it has to deal with the dignity of the laborer, that is, the fundamental character of the human person in all of his or her stages.

The song order of EEFP, consequently, follows this natural logic.

The opening track, a new one penned by Longdon, celebrates the joys of innocence. David has said it was his goal to invoke the glam rock of his childhood. For me, it invokes the rock of my mother’s college days. A shimmering, pre-Rolling Stones rock.

The video that the band released just makes me smile every time I watch it. The video also confirms my belief that these six (and Rob, the seventh member) really, really like each other.

Rather gloriously, “Make Some Noise” fades into one of the heroic of BBT tracks, “The First Rebreather.” This makes “The First Rebreather” even better, especially when contrasted with the innocence of track one. After all, in The First Rebreather, the hero encounters beings from Dante’s Fifth Circle of Hell (wrath).

The second new song, “Seen Better Days,” begins with a strong post-rock (read: Colour of Spring) feel, before breaking into a gorgeous jazz (more Brubeck than Davis) rock song. All of the instruments blend together rather intimately, and David sings about the founders and maintainers of early to mid 20th century British laboring towns, while lamenting the lost “power and the glory” as that old world as faded almost beyond memory. The interplay of the piano and flute is especially effective.

The third track, “Edgelands,” begins immediately upon the end of “Seen Better Days,” but it’s short. Only 86 seconds long and purely a Manner’s piano tune, it connects “Seen Better Days” with “Summoned by the Bells.” If at the end of those 86 seconds the listener doesn’t realize the creative talents of Mr. Manners, he’s not thinking correctly.

The fourth new track, “The Lovers,” appears on disk two, after “Winchester” and before “Leopards.” The most traditionally romantic and folkish song of the four new ones, Longdon’s voice has a very “Canterbury” feel on this tune, and the tune provides a number of surprises in the various directions it takes.

What’s next for BBT?

Thanks to the delights of social networking, we know that Danny’s kids are concerned that he doesn’t look “rock” enough (he needs to show them some Peter Gabriel videos from Gabriel’s last studio album), and we know that Greg’s middle name is Mark.

Ok, yes, I’m being silly (though all of the above is true).

We do know that Big Big Train is working on a retrospective of their history, but with the current lineup. I don’t think any of us need worry that this (Station Masters) will be some kind of EMI Picasso-esque deconstruction of Talk Talk with a “History Revisited: The Remixes.” Station Masters will be as tasteful, elegant, and becoming as we would expect from Greg and Co.

After that, we know that BBT is writing a full-fledged concept album, their first since The Difference Machine. We know that the boys are in the studio at the very moment that I’m typing this (NDV included).

Perhaps most importantly, though, we trust and have faith that Greg and Co. are leading progressive rock in every way, shape, or form. EEFP is the final version of EE. At least for now. But, BBT is not just breaking through, it’s bringing a vast audience, sensibility, and leadership to the entire third movement of prog. And, for this, I give thanks. Immense thanks.

When it comes to BBT, perfection only gets more interesting.

***

Making Much More than Noise: An Exclusive Interview with Greg Spawton

An exclusive interview with Greg Spawton of Big Big Train. Interview by progarchy editor, Brad Birzer. [N.B. I was going to write a longish introduction, but I’ll do that with the review of EEFP I’ll have up in the next day or two.]

***

Progarchy: Hello, again, Greg. I’m so glad you continue to be so generous with your time, and I’m deeply honored to have you do yet another interview with me. The order of the songs, BBT EE+4, is now set. In stone! How did you arrive at this ordering? I would guess you agonized over this, individually and as a group?

Greg Spawton: Thanks, Brad. We had four new tracks to accommodate and a listening experience as a long double album (as opposed to two single albums) to create and so there was a lot of discussion and consideration of various options. I wanted to create mini-suites out of some of the tracks with linked themes and that helped a bit as it drew some of the songs together. So, we had the Edgelands sequence of Seen Better Days / Edgelands / Summoned By Bells and the love-songs sequence with Winchester From St Giles’ Hill / The Lovers / Leopards and Keeper of Abbeys. Once those two sets of songs were in place it became easier to work the other tracks around them.

Progarchy: Do you see EEFP as a fundamentally different release from EE1 or EE2, or is it a fulfillment of the first two releases? A sort of baptism or sanctification?

Spawton: It’s a bit of both. Completists are likely to buy EEFLP even if they already own EE1 and EE2 and so we felt an obligation to create something new and different rather than just stick four new tracks on the end. But it also seems to have drawn all the threads together and, for us, it’s the ultimate expression of our work in this period of the band.

Progarchy: A followup, considering track order. You start with the very 1950s and 1960s rockabilly-ish “Make Some Noise,” but you end the entire collection with the–as I interpret the lyrics–suicide of the curator. Is this intentional?

Spawton: We knew those two songs had to be the bookends. Curator of Butterflies is not a song about suicide, although I can see why many people interpret it that way. It’s actually about life from the perspective of growing older. Now I’ve reached middle-age, I have a much greater awareness of how fragile life is. With my family and my good friends I find that awareness very burdensome. At home, I’m surrounded by teenagers and their take on life is entirely different. It’s fearless, they feel indestructible, they feel they have all the time in the world, whereas I sit back and wonder: ‘where did all the time go’? In Make Some Noise David captures the feelings of being young and full of hope and of dreams so we felt that had to be the opening statement. And as we had song from the perspective of an older person in Curator of Butterflies, it seemed right to put that one at the other end of the album.

Progarchy: Is the whole album, EEFP, still an album dealing with the dignity of labor, in all of its various forms?

Spawton: In old money, EEFLP is a triple album so there is room on there to explore a lot of different themes. One of the main themes of the album is about the dignity of labour. There have been major social changes in parts of Britain in the last 50 years and some communities in areas that used to rely almost solely on employment from the mines or docks or from heavy industry have lost their way because that employment has gone. I am not being nostalgic about this; I am well aware that those industries were very tough places to work. I spent a few minutes down a Victorian drift-mine recently and I cannot imagine what it would have been like to work a shift down there. However, what these industries did bring was a sense of pride in working hard and of the potential of communal endeavour. The loss of these things has been catastrophic for some communities.

Progarchy: Now that you’re done with EE–really three releases overall–how do you see your work with EE? That is, where does it fit in the history of BBT (besides, being the most recent thing)? How do you see it in the history of prog?

Spawton: If the band carries on in its current trajectory, we’re likely to end up selling about 30,000 copies of all of the EE albums. In the context of the huge 70’s progressive bands that is a tiny amount and we are only too aware that it can never have the sort of impact that Selling England by the Pound or Close to the Edge had. Having said that, it’s been a sequence of releases which has, I think, shown us at our best and has helped us to reach a wider audience and to get played on national radio in the UK. We’ve also grown as a band during the making of the albums. We are closer together as a unit and know what we can achieve. Danny has come onboard as keyboard player and has added a considerable amount to our sound. We’ve been able to work with a string quartet as well as the brass band and have been able to collaborate with some fabulous musicians and arrangers. And we are very pleased that we have been able to put together a release of 19 songs without any of them being there just to fill some space. Some songs are better than others, inevitably, but all have something to say and will, we hope, offer something to listeners.

Progarchy: A number of the new tracks reflect some really interesting influences, at least as I hear them. “Make Some Noise” seems very innocent and joyful, perhaps a pre-Byrds type of rock, the rock my mother danced to in college. “Seen Better Days” seems very Mark Hollis/Talk Talkish and then very jazzy. “Edgelands” again has a Talk Talkish feel. But, so very jazzy–an impressionistic jazz of the second half of the 1950s. “The Lovers” is proggy in a Canterbury, dramatic kind of way. Am I reaching, or were these influences intentional?

Spawton: I wouldn’t argue with any of those. We’re all fans of Talk Talk and the Canterbury scene. Influences are not something we think about during the creative process, though. I’d be a bit resistant to the idea of deliberately writing a song in the style of another band. For us, it’s an organic process of writing, arranging and performing. Influences often operate in a subliminal way and the writer may be unaware of how the listener will experience the songs.

Progarchy: The blending of songs into one another harkens back to The Difference Machine, and you’ve mentioned in a recent interview that your next studio album will be a concept album. Are you and BBT making a statement about where prog should be going with any of these decisions, or are you just taking your art as you feel so moved at the moment of creation?

Spawton: Honestly? We just write. Sometimes that is with something in mind (for example, where we need a song with a particular sound to help make a balanced album) but often it’s just what comes into our heads and falls under our fingers.

Progarchy: You’ve put so much into the booklet that accompanies EEFP. How much of the total art do you see in the packaging, the graphics, the photography. That is, how important is it to peruse the booklet rather than simply download the four new songs? We all lament the loss of the album sleeve, but you seem to have found away to recapture that glory. Again, was the booklet a group project, or did you work on this individually?

Spawton: Andy and Matt Sefton must take most of the credit for the overall design. Once we’d found Matt’s remarkable photos and he’d agreed to work with us, Andy was able to develop the overall shape of things using Matt’s images as the basis. The design of the packaging which carries our music is very important to us. Music is, of course, our primary concern and I have no problem with downloads. However, many people still prefer to experience music by purchasing physical releases and we put a huge amount of thought into making those items things of beauty and interest. Luckily, we found, in Chris Topham, a chap with a similar attention to detail for our vinyl releases and so we have worked with Chris and Plane Groovy to try to recapture the glory of the gatefold album cover.

Progarchy: A followup to the above question: you spend a significant part of the book honoring those that/who came before. As a historian, I love this. Again, how did you decide to do this? From my perspective, you’re tying in your work (adding all of those who contribute to BBT directly) with a whole lineage of English history and art. Any thoughts on the necessity and importance of this?

Spawton: I have been fascinated by history since I was a young child. In the 70’s, we had these beautifully-produced children’s books called Ladybird books in Britain and they were a big part of my early childhood. Looking back, they had a particular view of the world which wasn’t very nuanced (for example, the Roundheads were the goodies and the Cavaliers were the baddies) but they were spellbinding books with lovely artwork and they seemed to be able to transport me into those historic periods. As the band was developing I started to experiment with telling historical stories in the songs. Really, I think I’m just a frustrated historian without the outlet to write books so I used the ‘voice’ that I did have. I also began to become more aware of folk-music and that stories can be smaller and close to home and be just as interesting for people. And it’s the fact that the listeners are interested in these stories that has spurred me on. We get suggestions of stories sent to us now and there are so many interesting tales.

Progarchy: Again, somewhat related, it’s a stroke of genius to tie this release into the work–sadly, often forgotten or poorly remembered–of The Dukes of Stratosphear. Just how did you come to work with one of its members?

Spawton: When I got to know Dave Gregory I realised that he knew just about everybody in the music business. When we were working on The Lovers, David and Dave wanted the fusion section to be quite spacey and psychedelic and so we ended up asking Dave if he would mind giving Lord Cornelius Plum a call. Lord Plum hasn’t really been involved in music since The Dukes split up and we were delighted that he wanted to play a solo for us, albeit he insisted on playing the guitar backwards. I have to say, he’s still got the chops. He plays backwards guitar a lot better than I can play in the forward direction.

Progarchy: As you know, your fan base (getting larger, deservedly, by the moment!) craves knowledge about the future of BBT. Can you talk about how you plan to perform live? Where? With whom? When? What setlist (not exact, of course–no spoilers!)? Will Rob travel with you?

Spawton: Our live sound will be done by Rob, no question about that. We’re slowly gearing up for some live shows but we know that it requires careful planning. One of the things we are adamant about is that a live show will be an attempt to convey the whole BBT sound with brass and string sections. That is a complicated set-up and requires a fair bit of rehearsal. We’ve chosen Real World as a large studio environment which can accommodate us all and we are going to spend a week there next year working songs through and ironing out any live issues. The setlist will mainly feature songs from The Underfall Yard and English Electric, although we may also do some earlier songs. We’re going to film the rehearsals as that is a good way of recording a live set without the controlled chaos of being on stage. After Real World we’ll be looking to play a small number of shows and I think that we will then aim to play a handful of gigs every year. Just occasionally, progressive bands manage to crossover into a much broader audience (Steve Wilson being the best example) and, of course, if that happens then perhaps we can aim to tour more extensively. I think that is unlikely though and the main thing for us is not to try to put anything on that ends up losing a lot of money which could put the band’s finances out of kilter.

Progarchy: A followup. What about your future albums? Station Masters is coming in 2014. What about the next studio album? Can you tell us anything about it?

Spawton: Most of the next studio album is written and recording is under way. Nick is in England in late September so we’ll get another couple of days of drum recording done then. We may also do some recording at Real World. As you mentioned, it is a concept album with a story which David has been developing. It is not English Electric Part Three and it will be a little different but we are very excited about it. In the meantime, Station Masters is slowly moving forward and we aim for that to be a beautiful release.

Progarchy: What are the members of BBT listening to right now? If you could praise some current music, what would you praise? Or, any recent discoveries of older music? What about books? Anything that’s really grabbed your attention recently?

Spawton: There is so much great progressive music about at the moment and we have heard a number of excellent new releases so far this year. The nice thing is that we don’t feel in competition with anybody. There is a good feeling in progressive rock of us all being in it together, the bands and the listeners. Recently, I’ve had some fun working my way back though some of the classic 70’s albums and in the last few weeks I’ve been listening to a lot of Van Der Graaf Generator and PFM. I am looking forward to new music from Mew, Elbow and I have just bought the new Sigur Ros album. As for books, at the moment, I’m reading The Norman Conquest by Marc Morris and Britain Begins by Barry Cunliffe. And I’ve been reading a very interesting biography of Pink Floyd by Mark Blake. The book that has made the most impact on me in the last year was Working Lives by David Hall.

Progarchy: Again, Greg, thank you so much for your time. It’s always a pleasure.

Spawton: Thank you, Brad.

To order English Electric Full Power or the “Make Some Noise” EP, please click here.

Wait. Did you just miss that link? Here it is again:

To order English Electric Full Power or the “Make Some Noise” EP, please click here.

Andy Tillison on PROG AWARDS

Andy posted this at his personal facebook page. Very well worth reading and yet another reminder as to why Andy is a sheer modern (well, maybe post-modern) genius.

Some thoughts on the Prog Awards that took place in KEW, London last week. First of all, I had a great time and as I have already shown off on another thread, I got to share a table with three quarters of Transatlantic, Arjen Lucassen and the people from Insideout music who’d invited me. This in itself was a bit of a “wow” thing.

Looking around at the famous faces was worrying. I kind of realised that some hanger-on-to-1979-NME “everything must die so that punk may live” journalist could probably have wiped the genre from the face of the earth with a dodgy batch of Salmon Mousse. Rick Wakeman was right behind me, Ian Anderson, Dave Brock, Steve Hillage, Steve Hackett, Robert John Godfrey – Jeez!!! – if anyone had told me when I was at school that I’d be at this thing I’d have not believed them.

Most of my friends know that this kind of shindig is not really my scene. I felt a bit awkward in all posh clothes, a bit nervous to be with all the great and good – and this is not something that applies just to awards ceremonies, it goes back as far as “terror of the sixth form disco” and those student parties where you really DID find me, always in the kitchen. I’m just a bit nervous of formal events. Can’t be myself and that’s as simple as I can put it.

The formalities of the awards kicked off after a meal. Some of you know that my personal relationship with the organisation (PROG magazine) did not start quite as well as it might. My relationship with the editor and big chief there, Jerry Ewing, was worse than frosty for more than a year. Actually my fault when all is said and done – I really think most of it was to do with a bit of Northern Cantankerousness mixed with sense of humour failure and a little bit too much pride. And the fact that the mag had said that The Tangent looked like a bunch of Sheep Farmers and Accountants. I SHOULD have had a right old laugh about that. Because at the time, my partner Sally was working in accounts and we DID live in the middle of a sheep farm. Maybe it was just too close to the bone.

Ewing kicked off the proceedings with what, to my surprise and delight, was the most motivational speech of the night. It focussed heavily on the new bands both “real new” and “established new” and far from being corporate gesturing which is so often evident at this type of event, I got a real feeling that he MEANT it all, and that he didn’t actually see the third and fourth waves of Prog as some kind of pro-active fan club of the first and second. That was more than refreshing. And to watch the Von Hertzen Brothers claim their award, Big Big Train and Steven Wilson etc was great, knowing that there is, was and will be a lot of life in the genre AFTER 1977.

I’m always gonna be happier in jeans and a t-shirt, wrestling with a monitor mix at The Peel, The CRS, Summer’s End or Celebr8 than at a posh three course meal. And of course I did note that there were more people at the awards than are at most of the gigs. If all the musicians were to support each other at each others events we could significantly audience sizes – (but NOT ask to be on the guest list!!). But what’s really really great about these awards is that we’re all HERE, the old heroes and legends, the guys who want to follow them and the people who want to make it happen. I’ve always felt as a Prog musician to be “part of something” – of course I have.. but where so many negative correspondents have portrayed Prog as a safe, middle class and system supporting genre, I have always seen it as sticking up two fingers to the classical music establishment and saying “we can do that too” After all the shit, lies, misrepresentations and misunderstandings we’re ALL STILL HERE. Bring on the Salmon Mousse!!! We’ll survive that too!–Andy Tillison, Facebook, September 8, 2013