What makes a heavy record? What is heavy music?

What makes a heavy record? What is heavy music?

I still haven’t put my finger entirely on it. There are landmarks to go by. I think of the giant leap forward in production that Led Zeppelin achieved, where the drums and bass, really for the first time, were up front and PRESENT in a rock album, as Jimmy Page successfully married technology to sonic texture (it is amazing to think that a mere year and a half separated Zeppelin’s first from Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, in so many ways a touchstone for “produced” music, art rock, and progressive rock, but still quite thin sounding). Black Sabbath’s first, and then Paranoid, followed closely on the heels of Zep’s initial efforts, with Butler/Iommi/Ward’s dark conjurations so perfectly in tune with Geezer Butler’s lyrical mood and Ozzy’s keening wail. Then there’s the heaviness of message or melody or harmony, the lay-it-on-you trips of musical philosophy, that can blow down the walls even with the simplest of acoustic setups. I’ve never heard a punk-like shriek equal to Uncle Dave Macon’s banjo and voice records of the 1920s, or Charley Patton’s husky growl as it disappeared into the scratchy grooves of a worn Paramount 78. You want heavy? Patton’s heavy. Heaviosity is just what it is…I couldn’t tell you WHAT, but I know it when I hear it.

Successful progressive rock by definition is heavy music, as it seeks to differentiate itself from less self-consciously achieving music. Like any artful endeavor, it can utterly fail in the attempt, by stating the familiar without stretching towards the unknown. For instance, use of atonal or dissonant structures can only work as a dynamic shift between pieces (whether those pieces are albums or songs are parts within songs), in search of the sublime. As a repetitive reflex such devices are no more meaningful than a beautiful melody iterated too many times. Even music that relies heavily on drones can only do so because of the periodic resolutions or tonal completions.

Heavy music is the sound we hear made sacrosanct, often unknowably but assuredly.

I came to Popol Vuh later than I should have, years, decades, after I’d tuned into instrumental, meditative music (in the form of classical and jazz music). I was surprised when I did hear them that devotional music could be so obvious and compelling, and so far removed from the treacly mission-speak of Christian rock and its earnest minions. I’d heard of the band for a long time, I couldn’t say how long, and knew they were vaguely associated with new age music in the same way that Tangerine Dream were. That they were German may have sealed the deal to my overly threatened ears: nope, not going there. When I finally did listen, into my 30s by then, it was a revelation. A true classic, 1972’s Hosianna Mantra, dominated my stereo on Sunday mornings for a number of months, and still periodically does, guiding me through a non-denominational liturgy of the soul. Florian Fricke, Popol Vuh’s guiding genius and pianist, guitarist Connie Veit, and vocalist Djong Yun provide music to a common mass that knows no religious boundary. I’d like you to hear this, in the title track, Hosianna-Mantra:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kf8PWspETtc&feature=youtu.be

Veit’s gliss guitar provides a fluid compliment to Fricke’s piano, with the oboe and Djong Yun’s vocal floating as one above clouds of melodic invention. Intentional or not on the part of the musicians — and I believe it was, as Fricke had apparently experienced, not long before making this record, a rather intense religious conversion, part of which was abandoning his previous forays into electronic space music (equally wonderful, by the way) — it achieves a transcending spiritual glimmer, and is the single most compelling and inspiring expression of faith I have experienced in music. This is heavy music that is full of light, illuminating a path that Fricke and his collaborators in Popol Vuh would continue to follow for a number of years with an astounding level of success, whether in the music they created for Werner Herzog’s films in the 70s or on their own records.

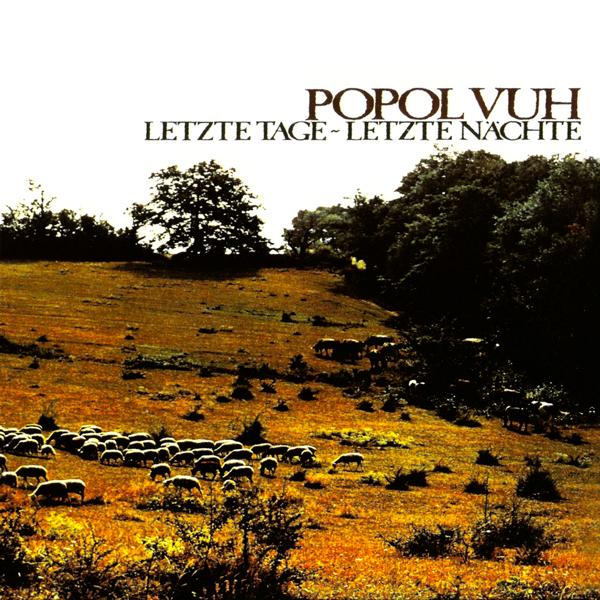

While Hosianna Mantra is often pointed to as Popol Vuh’s greatest achievement, it was a transitional record, heralding a string of albums where Connie Veit eventually left the group and Danny Fichelscher, a drummer and guitarist for Amon Duul II, joined, greatly influencing Popol Vuh’s sound. Fichelscher’s rock chording, accomplished solo-ing, and pounding drums gave sonic muscle to Fricke’s explorations, darkening the clouds. This is heard to greatest effect on the album Letzte Tage Letzte Nachte (Last Days, Last Nights), which at 30 minutes is one of the shortest progressive rock albums I can think of, and also is one of the heaviest records in my collection. There’s an eastern non-blues, metallic, marching sturm-und-drang that Fichelscher brought from Amon Duul II, and combined with Fricke’s melodic sensibilities this creates an atmosphere of shadow as well as light, broadening the reflective palette, retaining the beauty while at times adding an edge of dread. The first track, Der Grosse Krieger (The Great Warrior), inhabits this space, setting the tone for the rest of the album:

http://youtu.be/gdh-IhnhQd4

As on Hosianna Mantra, Djong Yun has a strong influence on Letzte Tage Letzte Nachte, but here it’s a harder rock turn, with her voice often joined to that of Renate Knaup, another Amon Duul II stalwart. Where on Hosianna Mantra, “Kyrie” was churchlike, solemn in its beauty, here “Kyrie” becomes a Hindu chant, with an almost Allman Brothers-like instrumental outro. The acoustic “Haram Dei Raram Dei Haram Dei Ra” continues the eastern om, leading into “Dort ist der Weg” (There is the Way), another dense electrical rock foray. The album concludes with the title track, a duet between Yun and Knaup, its fingerpicked arpeggios, reverberation, and repeated line, “When love is calling you, turn around and follow,” suggesting the more meditative work of U2.

http://youtu.be/KpPPElUV9Hg

Popol Vuh is heavy, and Popol Vuh is no more. Florian Fricke died in 2001, leaving a large and varied catalog of music behind him. Never content to stay in one place musically too long, and shunning the commercial potential his music certainly could have had in the New Age market had he done so, Fricke shared with many other “krautrock” pioneers a deep concern that music remain art, that it achieve a transcendence beyond simply making music or a day’s pay. He once said “Popol Vuh is a Mass for the heart” — his is a music well-described.

In the last few years, David Eugene Edwards has taken Wovenhand — soundstreamsunday #85 — in an increasingly heavy direction, towards drone metal underpinning an utterly unique and dead serious frontier circuit preacher mysticism. The drone as tribal, the ancient tool of ascension to the Common One, and so Wovenhand’s thunderous droning riffs on 2012’s Laughing Stalk and 2014’s Refractory Obdurate relate to themes steeped in Native American and old time music, eastern desert whirlwinds and western desert stoner rock. It is a vast music carrying a mad sensibility:

In the last few years, David Eugene Edwards has taken Wovenhand — soundstreamsunday #85 — in an increasingly heavy direction, towards drone metal underpinning an utterly unique and dead serious frontier circuit preacher mysticism. The drone as tribal, the ancient tool of ascension to the Common One, and so Wovenhand’s thunderous droning riffs on 2012’s Laughing Stalk and 2014’s Refractory Obdurate relate to themes steeped in Native American and old time music, eastern desert whirlwinds and western desert stoner rock. It is a vast music carrying a mad sensibility: