In part, a review of Rob Freedman, Rush: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Excellence (Algora, 2014).

N.B. This post should be approached with caution. It is at least PG-13, if not NC17. Not for language, but for personal revelation and content. Additionally, I’ve written about one or two of these things before, especially about Peart as a big brother. Please don’t fear thinking—“hey, I’ve read this before.” But, even the few things I’ve mentioned before are here rewritten. Final note: for an exploration of Peart’s Stoicism, see Erik Heter’s excellent piece on the subject, here at progarchy.com.

***

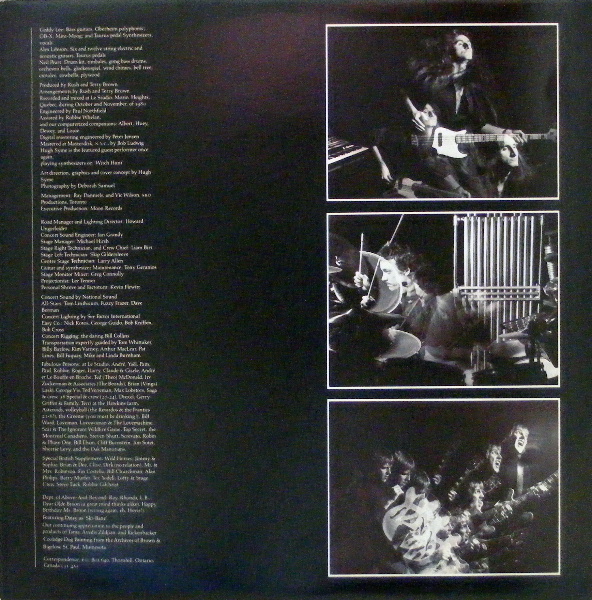

As I’ve mentioned before in these pages and elsewhere, few persons, thinkers, or artists have shaped my own view of the world as strongly as has Neil Peart, Canadian drummer, lyricist, writer, and all-around Renaissance man. I’ve never met him, but I’ve read all of his words and listened to all of his songs. I’ve been following this man since the spring of 1981 when two fellow inmates of seventh-grade detention explained to me the “awesomeness” of Rush. My compatriots, Troy and Brad (a different Brad), were right. Thank God I got caught for doing some thing bad that day. Whatever I did, my punishment (detention) led to a whole new world for me, one that would more than once save my life.

Having grown up in a family that cherished music of all types, I was already a fan of mixing classical, jazz, and rock. Rush’s music, as it turned out, did this as well as any band.

While the music captivated me, the lyrics set me free. I say this with no hyperbole. I really have no idea how I would have made it out of high school and through the dysfunctional (my step father is serving a 13-year term in prison, if this gives you an idea how nasty the home was) home life without Peart. I certainly loved my mom and two older brothers, but life, frankly, was hell.

I know that Peart feels very uncomfortable when his fan project themselves on him, or imagine him to be something he is not. At age 13, I knew absolutely nothing about the man as man, only as drummer and lyricist. Thus, even in 1981, I absorbed his lyrics, not directly his personality. Though, I’m sure many of Peart’s words reflect his personality as much as they reflect his intellect.

Rush gave me so much of what I needed in my teen years. At 13, I had completely rejected the notion of a benevolent God. He existed, I was fairly sure, but He was a puppet master of the worst sort, a manipulative, Machiavellian tyrant who found glee in abuse and exploitation. As a kid, I was bright and restless, and I resented all forms of authority, sometimes with violent intent. Still, as we all do, I needed something greater than myself, a thing to cherish and to hold, a thing to believe in.

I immersed myself in science fiction, fantasy, and rock music. Not a tv watcher in the least, I would put the headphones on, turns off the lights in my bedroom, lock the door, and immerse myself in the musical stories of Genesis, the Moody Blues, ELO, ELP, Alan Parsons, Yes, Jethro Tull, Pink Floyd, and, especially, Rush. I could leave the horrors of my house for roughly 44 minutes at a time.

Scratch, scratch, side one. Zip, turn. Scratch, scratch, side two.

Rock music was the sanctuary of my world. But, not just any rock. ZZ Top and REO Speedwagon might be fun when out on a drive, but I needed a work of art that demanded full immersion. I needed prog. I was not only safe in these rhythmic worlds, I was intellectually and spiritually alive, exploring innumerable realms. Pure, unadulterated escape. But, escape into a maze of wonders.

The first time I heard the lyrics (at age 13, the spring of 1981) to “Tom Sawyer,” I knew Rush was MY band. It seemed as though Peart was talking specifically to me, Bradley Joseph Birzer. That’s right. To 13-year old Brad in Hutchinson, Kansas. Peart was 15 years older than I, and he must have gone through the same things I had. Or so I thought. Again, I knew him only through his lyrics. But, did I ever cherish those lyrics. I lingered over each word, contemplated not just the ideas, but the very structures of lyrics as a whole.

Though his mind is not for rent

Don’t put him down as arrogant

His reserve a quiet defense

Riding out the day’s events

No, his mind is not for rent to any God or Government

Always hopeful, yet discontent [corrected from my original typos]

He knows changes aren’t permanent, but change is

Though I’ve never given any aspect of my life to the Government (nor do I have plans to do so), I long ago surrendered much of myself to the Second Person of the Most Blessed Trinity and to His Mother. While I’m no modern Tom Sawyer at age 47, I still find the above lyrics rather comforting. And, I do so in a way that is far beyond mere nostalgia.

Armed with Peart’s words and convictions, I could convince myself to walk to Liberty Junior High and, more importantly, to traverse its halls without thinking myself the most objectified piece of meat in the history of the world. Maybe, just maybe, I could transcend, sidestep, or walk directly through what was happening back at home. I could still walk with dignity through the groves of the academy, though my step father had done everything short of killing me back while in our house.

[N.B. This is the PG13 part of the essay] And, given all that was going on with my step father, the thought of killing myself crossed my mind many, many times in junior high and high school. I had become rather obsessed with the notion, and the idea of a righteous suicide, an escape from on purposeless life hanged tenebrous across my soul. After all, if I only existed to be exploited, to be a means to end, what purpose did life have.

What stopped me from ending it all? I’m still not sure, though such desires seemed to fade away rather quickly when I escaped our house on Virginia Court in Kansas and began college in northern Indiana. Not surprisingly, my first real friendship in college—one I cherish and hold to this day—came from a mutual interest in all things Rush. In fact, if anything, my friend (who also writes for this site) was an even bigger Rush fan than myself! I’d never met such a person.

Regardless, from age 13 to 18, I can say with absolute certainty that some good people, some good books, and some good music saved my life, more than once. Neil Peart’s words of integrity and individualism and intellectual curiosity stood at the front and center of that hope.

Perhaps even more importantly to me than Moving Pictures (“Tom Sawyer,” quoted above) were Peart’s lyrics for the next Rush album, Signals. On the opening track, a song about resisting conformity, Peart wrote:

Growing up, it all seemed so one-sided

Opinions all provided, the future predecided

Detached and subdivided in the mass production zone

No where is the dreamer or misfit so alone

There are those who sell their dreams for small desires

And lose their race to rats

Even at 14, I knew I would not be one who sold my dreams for small desires. I wanted to be a writer—in whatever field I found myself—and I would do what it took to make it through the horrible home years to see my books on the shelves of a libraries and a bookstores. Resist and renew. Renew and resist. Again, such allowed me to escape the abyss of self annihilation.

Indeed, outside of family members (though, in my imagination, I often think of Peart as one of my older brothers—you know; he was the brilliant one with the goofy but cool friends, the guys who did their own thing regardless of what anyone thought). From any objective standpoint, as I look back over almost five decades of life, I can claim that Peart would rank with St. Augustine, St. Francis, John Adams, T.S. Eliot, Willa Cather, Ray Bradbury, Russell Kirk, and J.R.R. Tolkien as those I would like to claim as having saved me and shaped me. If I actually live up to the example of any of these folks, however, is a different question . . .

I also like to say that Peart would have been a great big brother not just because he was his own person, but, most importantly, because he introduced me as well as an entire generation of North Americans (mostly males) to the ideas of Heraclitus, Plato, Aristotle, Sophocles, Cicero, Seneca, Petrarch, Erasmus, Voltaire, Adam Smith, Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, T.S. Eliot, J.R.R. Tolkien, and others.

During my junior year of high school, I wrote an essay on the meaning of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, based on Peart’s interpretation. I earned some form of an A. In one of my core humanities courses, while at the University of Notre Dame, I wrote my major sophomore humanities term paper about the cultural criticisms of Neil Peart as found in his lyrics to the 1984 album, Grace Under Pressure. Again, I received an A.

I’m not alone in this love of Rush. The band is, of course, one of the highest selling rock acts of all time, and they are just now crossing the line into their fortieth anniversary. Arguably, no other band has had as loyal a following as had Rush. Thousands and thousands of men (and some women) faithfully attend sold-out concerts throughout North and South America to this day. This is especially true of North American men, ages 35 to 65. Now, as is obvious at concerts, an entirely new generation of Rush fans is emerging, the children of the original set.

Telling, critics have almost always despised Rush, seeing them as having betrayed the blues-based tradition of much of rock, exchanging it for a European (and directly African rather than African-American) tradition of long form, complexity, and bizarrely shifting time signatures. Such a direction and style became unbearable for the nasty writers of the largest music magazines. They have felt and expressed almost nothing but disdain for such an “intellectually-pretentious band,” especially a band that has openly challenged the conformist ideologues of the Left while embracing art and excellence in all of its forms. Elitist rags such as the horrid Rolling Stone and equally horrid NME have time and time again dismissed Rush as nothing but smug middle-class rightists.

That so many have hated them so powerfully has only added to my attraction to the band, especially those who came of age in 1980s, despising the conformist hippies who wanted to mould my generation in their deformed image. Rolling Stone and NME spoke for the oppressive leftist elite, and many of my generation happily made rude gestures toward their offices and their offal. I had no love of the ideologues of the right, either. But, they weren’t controlling the schools in the 1980s. Their leftist idiotic counterparts were in charge. They had no desire for excellence. They demanded conformity and mediocrity.

[The best visual representation of this widespread if ultimately ineffective student revolt in the 1980s can be found in “The Breakfast Club” by John Hughes (RIP).]

To make it even more real for me, the parents of Geddy Lee, the lead singer and bassist of Rush, had survived the Polish holocaust camps, and the parents of Alex Lifeson, the lead guitarist of the band, had escaped from the Yugoslavian gulag. Peart came from a Canadian farming community, his father an entrepreneur. No prima donnas were these men. They understood suffering, yet they chose to rise above it. And, of course, this makes the British music press even more reprehensible for labeling the members of Rush as rightest or fascist. Again, I offer the most dignified description for Rolling Stone and NME possible: “ideological fools and tools.”

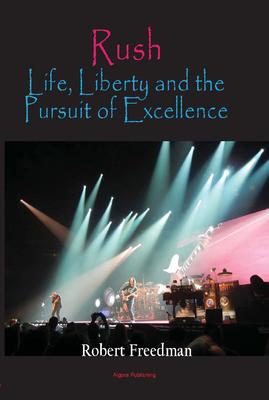

Enter Rob Freedman

In his outstanding 2014 book, Rush: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness (Algora Press), author, philosopher, and media specialist Rob Freedman has attempted to explain not just Peart’s popularity among his multitude of fans—some of the most dedicated in the music world—but also the Canuck drummer’s actual set of ideas and explored beliefs in his books and lyrics. Not surprisingly, Freedman finds the Canadian a man deeply rooted in the western tradition, specifically in the traditions of western humanism and individualism.

As Freedman notes, one can find three themes in all of Peart’s lyrics: individualism; classical liberalism; and humanism. It’s worth observing that Freedman has formal training in academic philosophy, and this shows in his penetrating discussion of the music as well as the words of Rush.

Relying on interviews with the band, the music journalism (much of it bogus and elitist idiocy) of the last forty years, and actually serious works of Rush criticism, such as that done admirably by Steve Horwitz in Rush and Philosophy (Open Court, 2011), Freedman offers not so much a biography of the band, but rather a map of their intellectual influences and expressions. Freedman possesses a great wit in his writing, and the book—relatively short at 164 pages—flows and flows, time standing still until the reader reaches the end. For all intents and purposes, Freedman’s book serves as an intellectual thriller, a page turner.

As a lover of Rush, I have a few (very few) quibbles with Freedman’s take. Mostly, from my not so humble perspective, Freedman gives way too much space to such charlatans as Barry Miles of the English New Music Express who claimed Rush promoted neo-fascism in the late 1970s. Freedman, while disagreeing with Miles, bends over backwards defending Miles’s point of view, as it did carry immense weight in the 1970s and wounded the band deeply. From my perspective, there is no excuse for Miles. He maliciously manipulated and twisted the words of Peart—using his lyrics and a personal interview—which were as deeply anti-fascistic as one could possibly imagine (paeans to creativity and individualism) and caused unnecessary damage to the reputation of three men, two of whom who had parents who had survived the horrors of the twentieth-century ideologues, as noted above. Miles’s take on Rush is simply inexcusable and no amount of justification explains his wickedness and cthluthic insensibilities toward three great artists. Dante best understood where such “men” spent eternity.

I also believe that Freedman underplays the role of Stoicism in his book. The venerable philosophy barely receives a mention. Yet, in almost every way, Peart is a full-blown Stoic. In his own life as well as his own actions, Peart has sought nothing but excellence as conformable to the eternal laws of nature. This is the Stoicism of the pagans, admittedly, and not of the Jews or Christians, but it is Stoicism nonetheless. Freedman rightly notes that Plato and, especially, Aristotle influenced Peart. But, so did Zeno, Virgil, Cicero, and Seneca. This comes across best in Peart’s lyrics for “Natural Science” (early Rush), “Prime Mover” (middle Rush), and in “The Way the Wind Blows” (recent Rush). In each of these songs, Peart presents a view of the world with resignation, recognizing that whatever his flaws, man perseveres. Erik Heter and I have each attempted to explore this aspect of Peart’s writings at progarchy. Heter has been quite successful at it.

As the risk of sounding cocky, I offer what I hope is high praise for Freedman. I wish I’d written this book.

Peart as Real Man

In the late 1990s, Peart experienced immense tragedy. A horrible set of events ended the life of his daughter and, quickly after, his wife. Devastated, Peart got on his motorcycle (he’s an avid cyclist and motorcyclist) and rode throughout the entirety of North America for a year. It was his year in the desert, so to speak.

Then, in 2002, Rush re-emerged and released its rockingly powerful album, Vapor Trails. The men were the same men (kind of), but the band was not the same band. This twenty-first century Rush, for all intents and purposes, is Rush 2.0. This is a much more mature as well as a much more righteously angry and yet also playful Rush. This is a Rush that has nothing to prove except to themselves. The last albums—Vapor Trails (2002); Snakes and Arrows (2007); and Clockwork Angels (2012)—have not only been among the best in the huge Rush catalogue, but they are some of the best albums made in the last sixty years. They soar with confidence, and they promote what Rush has always done best: excellence, art, creativity, distrust of authority, and dignity of the human person.

Peart is not quite the hard-core libertarian of his youth. In his most recent book, Far and Near, he explains,

The great Western writer Edward Abbey’s suggestion was to catch them [illegal immigrants], give them guns and ammunition, and send them back to fix the things that made them leave. But Edward Abbey was a conservative pragmatist, and I am a bleeding-heart libertarian==who also happens to be fond of Latin Americans. The ‘libertarian’ in me thinks people should be able to go where they want to go, and the ‘bleeding heart’ doesn’t want them to suffer needlessly” [Far and Near, 58]

If he has lost any of his former political fervor, he’s lost none of his zest for life and for art. “My first principle of art is ‘Art is the telling of stories.’ What might be called the First Amendment is ‘Art must transcend its subject’.” [Far and Near, 88]

These twenty-first century albums speak to me at age 47 as much as the early albums spoke to me at age 13. I’ve grown up, and so has Rush. Interestingly, this doesn’t make their early albums seem childish, only less wise.

After my wife and I lost our own daughter, Cecilia Rose, I wrote a long letter to Neil Peart, telling him how much the events of his life—no matter how tragic—had shaped my own response to life. I included a copy of my biography of J.R.R. Tolkien. Mr. Peart sent me back an autographed postcard as thanks.

I framed it, and it will be, until the end of my days, one of my greatest possessions.

After all, Neil Peart has not just told me about the good life, creativity, and integrity, he has shown me through his successes and his tragedies—and thousands and thousands of others—that each life holds a purpose beyond our own limited understandings. As with all things, Peart takes what life has given and explodes it to the level of revelation.