Tag: Rush

On a Silver Salver: The Miracle of 1984, Part I

As I mentioned yesterday (https://progarchy.com/2014/03/19/1994-a-pretty-good-year/), I thought 1994 was a “pretty good year” for music. Thinking about 1994 made me think about 1984, and, methinks (don’t you hate it when writers use such pretentious words! Ha), 1984 puts 1994 to shame. In fact, it puts many, many years to shame.

As a product of midwestern America, Ronald Reagan will always dominate my main image and memory of 1984. I write this nonpolitically. Whatever you thought of Reagan as a leader, the man wielded supernatural charisma. He was, simply put, a presence.

But, other images emerge as well from 1984: movies such as 16 Candles, Red Dawn, and The Killing Fields. Chernyanko becoming head of the Soviets. Paul McCartney arrested for possession of pot. The fall of AT&T. The arrival of the first Macintosh. What a year.

Beyond the above, I most remember the music. What a year of greatness for those of us who love innovation and beauty in music. So without further bloviation, I offer my favorites of that august year.

***

Rush, Grace Under Pressure. This is not only my favorite Rush album, it was and remains my favorite album of 1984. I’ve written about this elsewhere, but it’s worth noting again that I think Rush perfectly captured the tensions of that year: the horrors of the gulags; the destruction of the environment; the loss of a friend; and so on.

I hear the echoes, I learned your love for life

I feel the way that you would

***

Thomas Dolby, The Flat Earth. I’ve written about this album as well. So brilliant. As deep and as meaningful as Dolby’s first album was interesting and novel.

Suicide in the hills above old Hollywood

Is never gonna change the world

***

Ultravox, Lament. My favorite Ultravox album? Maybe. As much as Rush captured the spirit of the year, so did Ultravox. From the worry expressed in “White China” to the longing of “When the Time Comes,” Lament is a masterpiece.

Will you stand or fall, with your future in another’s hands

Will you stand or fall, when your life is not your own

***

Talk Talk, It’s My Life. While this is certainly not Talk Talk’s best album, it is quite good. In particular, Hollis reveals much of his genius in songwriting, whatever the “new wave” trappings of the song. Underneath whatever flesh the band gave the music, the lyrics cry out with a poetic lamentation of both confusion and hope.

Talk Talk, It’s My Life. While this is certainly not Talk Talk’s best album, it is quite good. In particular, Hollis reveals much of his genius in songwriting, whatever the “new wave” trappings of the song. Underneath whatever flesh the band gave the music, the lyrics cry out with a poetic lamentation of both confusion and hope.

The dice decide my fate, that’s a shame

In these trembling hands my faith

Tells me to react, I don’t care

Maybe it’s unkind if I should change

A feeling that we share, it’s a shame

***

Simple Minds, Sparkle in the Rain. Again, while this isn’t the best Simple Minds had to offer, it was the last great gasp of the band before entering into an overwhelming celebrity. Kerr’s Catholicism especially reveals itself in songs such “Book of Brilliant Things” and “East at Easter.”

I thank you for the shadows

It takes two or three to make company

I thank you for the lightning that shoots up and sparkles in the rain

Neil Peart: The Most Endangered Species

Some songs just scream “let me reach perfection.”

Every note, every pause, every ebb, every swell, every silence, and every word just gravitates towards its right place. It’s as though the cardinal and Platonic virtue of Justice becomes manifest, real, and tangible in this world.

There probably are very few perfect tracks—tracks that never grow old and never cease to cause wonder. From the 70s and 80s the following immediately spring to mind as candidates: The Battle of Evermore, In Memory of Elizabeth Reed, Close to the Edge, In Your Eyes, Thick as a Brick, Cinema Show, Take a Chance with Me, Echoes, and The Killing Moon.

Of all of these great possibilities from those two wild and wholly decades, the one song that comes closest to attaining perfection, such as perfection is understood in this rather bent world, is Natural Science, the final track on Rush’s Permanent Waves.

Well, at least in my humble opinion. Ok, not so humble of an opinion.

Unobjectively Rushed

In a number of previous posts here at progarchy and elsewhere, I’ve talked about my love for all things Rush, perhaps even putting myself in a position in which I simply can’t be objective about them. Frankly, at age 46, I’m tired of trying to be objective about the things I love. In fact, I want to be subjective. Really, really subjective. I want to spend the rest of my life promoting things of excellence and beauty, and not wasting my time analyzing what I don’t like. I want to explore how various forms of art have shaped my own life, how they’ve guided me, how they’ve given me strength and comfort, and how best to pass on such nuggets of insight to my children and my students.

So, purely subjectively: I’ve always thought of Neil Peart as the older brother I never had—the cool kid with all the great ideas and, equally important, the guy with all of the good friends. Most importantly, however, Peart has always had the courage of his convictions. What an appealing combination of qualities. Creativity, intelligence, integrity and perserverance.

As much as any person in my life I’ve never met (from Plato to St. Augustine to Friedrich Hayek to T.S. Eliot to J.R.R. Tolkien), Peart has profoundly shaped my view of the world. I’ve known this since the spring of 1981, when, as a seventh grader, I first encountered Moving Pictures.

And, coming from a very (happily) nerdy and intellectual family which encouraged a love of music as much as it encouraged a love of reading and writing, I started writing my own first little essays on Rush while still in high school.

Perhaps my professors in college shouldn’t have allowed me to do this or encouraged me, but I did get to help lead a discussion on the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, using the song “Tom Sawyer” to explain the significance of the end of Twain’s novel. The end of that complex novel tries to examine the motivations of Huck and Tom as they decided whether or not to free Jim from his enslavement. Their humanity tells them one thing, but their cultural upbringing tells them another.

I also, as I’ve mentioned before, wrote my major paper for my sophomore liberal-arts core course examining the philosophy of Neil Peart, using nothing but the lyrics of Grace Under Pressure. Sadly, I don’t have a copy of that paper any longer, though I might attempt to reconstruct it at some point.

Natural Science

I can identify almost every single moment in my post-1980 life with a Rush album—noting when I first encountered that album, how it shaped my own thoughts, life, and actions, and what else was going on in my life at the same time. Certainly, Rush has served as the soundtrack of my own existence for over three decades. Strangely, the one album in Rush’s entire catalogue I can’t place perfectly—at least when I first encountered it—is Permanent Waves. I’m guessing that I first heard it shortly after Spring 1981, but I’m not positive. It just seems to have always been “there.” There, meaning my life. This is impossible, of course, as I was 11 when the album first came out, but it does seem to have an uncertain yet certain position in my memory.

I still regard the entire album as a work of artistic intensity and creative genius. There’s a confidence that exists in every note of this album that had not yet appeared in Rush’s music. Don’t get me wrong—up to Permanent Waves, Rush had always possessed audacity and integrity. But, they’d not possessed this level of confidence before. Songs such as Anthem—so openly declaring confidence—reveal youthful anxiety. But, the personal aspects of Permanent Waves, such as in “Free Will,” carry with them a rather clear maturity.

To my mind, none of the songs carry as much confidence, however, as does Natural Science. Originally, as is well known by Rush fans, Peart had hoped to write a saga, epic, or edda about the Court of King Arthur and especially about the character of Sir Gawain.

I had also been working on making a song out of a medieval epic from King Arthur’s time, called ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight’. It was a real story written around the 14th century, and I was trying to transform it while retaining it’s original form and style. Eventually it came to seem too awkwardly out of place with the other material we were working on, so we decided to shelve that project for the time being…with the departure of ‘Gawain’ we had left ourselves nothing with which to replace him!…something new began to take shape. It was the product of a whole host of unconnected experiences, books, images, thoughts, feelings, observations, and confirmed principles, that somehow took the form of ‘Natural Science’…forged from some bits from ‘Gawain’, some instrumental ideas that were still unused, and some parts newly-written. – Neil Peart, “Personal Waves, The Story Of An Album” [taken from: http://www.2112.net/powerwindows/main/RushInspirations.htm]

Though I don’t know this for certain, I assume that Peart was still in a bit of a myth/fantasy/Tolkien stage as he considered the lyrics for this song. Best known by the world for his fiction, J.R.R. Tolkien was in his professional life the leading scholar of the medieval literature of Beowulf, Sir Gawain, and others. In the late 1970s, Tolkien’s publisher attempted to capitalize on success of The Silmarillion by re-publishing almost everything Tolkien had ever written, including his academic work, repackaged for a popular audience.

Many of the ideas in Natural Science, at least musically, also came from a “mass of ideas called Uncle Tounouse” [Popoff, CONTENTS UNDER PRESSURE, 76; http://rushvault.com/2011/02/05/natural-science/; and http://www.2112.net/powerwindows/main/PeWlyrics.htm%5D

At 9 minutes, 17 seconds, “Natural Science” consists of three parts: Tide Pools; Hyperspace; and Permanent Waves. These might have also have been titled, less poetically, Nature; Science; and Integrity.

In Part I, “Tide Pools,” Peart offers a vision of community. Each person is born into a myriad of factors. As the great Irishman, Edmund Burke, once said before Parliament: “Dark and inscrutable are the ways in which we come into the world.” Each person is born into a family, an environment, a language, a set of morality, a religious system (even if atheist), etc. Each of these factors shapes and delimits our very beings, and we must—from our earliest infancy—learn to move from one realm into another. From, for example, our family to our school. We must transition, we must bridge, we must understand, and we must integrate our experiences. Such a world of communities brings us security, but it might also allow for an insular kind of inbreeding and sloth. Looking at all of the connections and interactions, though, overwhelms us.

Wheels within wheels in a spiral array,

A pattern so grand and complex,

Time after time we lose sight of the way,

Our causes can’t see their effects.

Part II, “Hyperspace,” reveals how insane an integrated, uniform culture might before. Peart’s vision of conformity here is not of a communist or fascist variety, but instead of a capitalist, consumerist variety. It might metastasize uncontrollably.

A mechanized world out of hand.

Computerized clinic

For superior cynics

Who dance to a synthetic band.

In their own image,

Their world is fashion.

No wonder they don’t understand.

Part III, “Permanent Waves,” brings the story and listener to a stoic resignation, a realization that one must somehow and in some way recognize the limits as well as the advantages of an insular natural community and a hyper collectivist consumerism, brought together by (I presume) colossal bureaucracies of corporations, educational systems, and governments.

The true man, whatever the odds against him, will survive.

The most endangered species,

The honest man,

Will still survive annihilation.

Forming a world

State of integrity,

Sensitive, open and strong.

These are quintessentially Peartian themes, and he will return to them again and again in his lyrics. “Subdivisions,” for example, offers almost all of the same sentiments, but it does so in lyrics that are much more direct. The lyrics for Natural Science remain far more poetic than intellectual, far more artistic than philosophical. And yet, they are poetic, intellectual, artistic, and philosophical all at once.

They are. . . well, Peartian. Very Peartian.

Words of Friendship and Wisdom

In the summer of 1987, having completed my first year of college, I returned back to my hometown of Hutchinson, Kansas. It was one of the best summers of my life, as all of my high school friends were home, and I had the best job possible—I was the overnight DJ at a local radio station. In my mind, this really was the last year of my youth. I didn’t realize that at the time, but I do now. It was also, though, a summer of immense upheaval. The following school year, I wouldn’t be returning to the University of Notre Dame. Instead, I moved to Innsbruck, Austria, for a year. At home, a number of domestic crises would lead to a divorce. As much as I loved my mom, I needed to get away from the home front quickly. All of this added up to a summer of craziness, me being a little more wild than I should have been.

Trying to get me back on track, one of my two closest college friends sent me a letter toward the end of that summer. Inside, written on rice paper, neatly folded, were the lyrics to Natural Science, with a note of encouragement.

I carried that piece of folded rice paper with me—tucked in my wallet—for about two decades. It’s very hard to put into words what Peart’s thoughts in “Natural Science” did for me. “Natural Science” did for me in my 20s and 30s, what “Subdivisions” had done for me at 14. They gave me no easy answers or platitudes, but honesty and courage. They got me through many, many tough times, never failing to remind me that right has absolutely nothing to do with winning or losing. Right, instead, has to do with being right. Nothing more, nothing less. We do the right thing not for advantage, but merely and simply because it’s right. It’s not subjective. It’s either right, or it’s not. It’s not partially right or almost right. It’s either right, or it’s not.

Sometimes, we just need a big brother or a friend to remind us of these things.

Neil Peart, moral philosopher, “sensitive, open, and strong.”

*******

For more from Progarchy on Rush

The first Rush album reviewed by Craig Breaden

https://progarchy.com/2014/02/22/rushs-first/

A review of A Farewell to Kings by Kevin McCormick

https://progarchy.com/2013/01/21/rush-a-farewell-to-hemispheres-part-i/

A review of Power Windows by Brad Birzer

https://progarchy.com/2013/12/14/power-windows-rush-and-excellence-against-conformity/

Kevin Williams on Clockwork Angels Tour

https://progarchy.com/2013/11/24/rushs-clockwork-angels-tour-straddles-the-80s-and-the-now/

Brad Birzer on Clockwork Angels Tour

https://progarchy.com/2013/11/27/rush-2-0-clockwork-angels-tour-2013-review/

Erik Heter on Clockwork Angels Tour Concert in Texas

A review of Vapor Trails Remixed by Birzer

https://progarchy.com/2013/10/05/resignated-joy-rush-and-vapor-trails-2013/

A review of Grace Under Pressure by Birzer

https://progarchy.com/2013/02/21/wind-blown-notes-rush-and-grace-under-pressure/

Rush’s First

Rush landed in my life like a broken window when I was thirteen, that weird, shard-like spiral guitar intro to The Spirit of Radio busting things open for me in 1980. It wasn’t an easy sell at first — Rush is a studied taste and I’d still say on most Rush records for every moment of musical or lyrical poetry there are two that are just brainy. What maybe distinguishes the band, though, is their absolute, all-in commitment to THEIR muse as a trio. It’s been mentioned in these pages before, but worth reiterating: Rush is as powerful now as they were 40 years ago, despite just about every obstacle you can throw at an artist.

Forty years ago next month Rush released its first, self-titled album. In its way it’s one of the most intriguing records in their catalog because, unlike almost every other one of their albums, it is a product of its time and shows it. That it’s also a prime example of early 70s hard rock is often lost in the various fanboy legends of Rush, where all songs are anthems and where first drummer John Rutsey is alternately pitied or maligned for not being Neil Peart. Rush the album is a tight, finely-walked tour of guitar rock, a thick, sludgy, power trio slab that screams North American midwest, 1974. There are odes to hard working folks, stoner rock birds flipped at the Man, ballads and blues boogie admonitions to the ladies, and hard luck stories from the rock and roll road. This was not a lightly-traveled terrain: Mountain, Robin Trower, and armies of Uriah Heep-ish bands were all pounding to dust the path blazed by the Yardbirds then Cream then Zep, and Rush was very much a part of the meat-and-potatoes rock circuit that included bands like REO Speedwagon and the Amboy Dukes.

But Rush intrigues for a number of reasons, not least of which because as a record it shows a working rock band fully constructed. They were young but had paid their dues, there was no doubt, witnessed by the super tight performances. And looking back at the record 40 years on, there are moments when Alex Lifeson’s chord voicings or Geddy Lee’s bass patterns seem to jump forward to their present work. They had a kernel of a sound and a whole lot of chops, and I’d argue that when they replaced Rutsey with Peart they possessed an uncommon strength, which allowed them to deconstruct their sound and build it up again, to eventually realize a vision absolutely unique in rock.

Technically, too, the record has a lot to recommend it. Working with limited technology, even for the era, the band created an album with a saturated, present guitar sound that was clearly evolving with what could be reproduced on a record. The separation is very good, although the drums don’t always pop like they could, probably as a result of the guitar’s appetite for bandwidth, rather than Rutsey’s playing, which swings with the best hard rock records of the time. The extended soloing space, too, is defined and disciplined, guitar-focused and deriving more than a little from the studio recordings of Led Zeppelin, one of Rush’s early beacons. Rush had their ears on this recording, and I don’t think it’s any mistake that more recent stoner and heavy rock records have a lot in common sonically with Rush’s first.

Thirty years after Rush released its first record, they recorded Feedback, an homage to their influences. Played back to back with Rush, the two albums almost seem of a pair, their respective sounds not that unlike, and as if the songs on Feedback might have made up the rest of the set had you seen the band in ‘72-73. Feedback arrived two years after Vapor Trails, when Rush re-asserted its harder, guitar-focused edge, and began a phase of fine work that continues up to their most recent record, Clockwork Angels. As the title of that album suggests, this is a band that appreciates the spiral and the cycle of their art, the seed of which can be heard, if you’re listening for it, on Rush.

Long Live Rock: Boston Brightens the World with Life, Love, and Hope

In a nice coincidence, during the same time that Brad was writing and has posted his Progarchy Editorial on “The End of Rock,” I have been listening to and enjoying the new Boston CD released back in December, “Life, Love, & Hope.”

Boston has a great sound that can best be described with the adjective “soaring” — as in: soaring guitar riffs, soaring lead lines, soaring organ solos, and incredibly rich layers of soaring vocal harmonies. No wonder their signature album cover look has always been one that depicts guitars as spaceships.

I am happy to report that the new Boston album is a work of excellence. Tom Scholz has always been a perfectionist and he is very famous for his protracted battles with record companies. After he was pressured to use a non-basement studio to re-record the demo tracks for the original Boston album (1976), and after he was pressured to release the second Boston album without being fully happy with it (Don’t Look Back — 1978), Boston albums have ever since only come out at the rate of about one per decade: Third Stage (1986), Walk On (1994), Corporate America (2002), and now Life, Love, & Hope (2013).

Scholz prefers to be a loner in the studio, in order to best pursue excellence through perfectionism. There has always been something wonderfully “prog” about Scholz’s insanely detailed musical devotion. There are abundant examples of musical virtuosity on Boston records, but just take “Foreplay/Long Time” from Boston (1976) if you would dispute placing Boston in the prog pantheon. And Scholz can achieve stratospheric musical heights in just a two minute instrumental — for example, take either “Last Day of School” or “O Canada” from the new album — thus demonstrating how he can soar even higher than what the average prog band can attain in even ten minutes.

It was interesting to read Brad’s editorial and at the same time try to imagine an album like Boston (1976) being released today and achieving similar mass acclaim with sales figures of over 17 million. What a cultural loss that we cannot hear any tracks from the new Boston album being played across all radio stations everywhere! The youth of today are suffering a great deprivation.

For my part, I am thankful that I encountered Boston at the age I did. For me, Boston in effect was “starter prog,” as the excellence that they conveyed in “More Than a Feeling” opened me up to the transcendent possibilities available through music. “More Than a Feeling” was a true revelation, and my love of that song has never changed. It sounds as magical to me now as when I first heard it.

It’s a genuine thrill that Scholz is still devoted to his uncompromising art and that this new album has caught me off guard by being so darn good. Every track is wonderful and I will have to post further at Progarchy about it.

For now, in the spirit of Brad’s excellent editorial, I just wanted to share with you what Scholz writes in the liner notes. His note shows that the heart of rock and roll is still beating, and that the spirit of prog is what animates that beating heart. Now, you may perhaps know that spirit by one of its more well-known names — “The Spirit of Radio” — but for me, because of what I learned early on from Scholz, I have always known that that spirit is a spirit that is indeed “More Than a Feeling”:

When I started recording this album over ten years ago, who’d have thought I’d still be working on it in 2013? OK, don’t answer that. These are all songs from the heart, each of them taking many months of effort to write, arrange, perform and record, always up to the demands of BOSTON’s harshest critic, me. They have all been meticulously recorded to analogue tape on the same machines and equipment used for BOSTON’s hits for the past 35 years.

After the internet and digital file sharing knocked the foundation out from under the music business, it no longer became possible to record a full production analogue album like this one, unless you were willing to do it purely for the art. I found out that I was. But as the years wore on, struggling with obstinate pieces, over-stressed gear, and my own uncertainty, I sometimes wondered if these songs would ever see the light of day. Now, listening to the album, I feel like I have burst from a dark tunnel of seemingly endless solitary work and self-doubt into a bright new world. If any of these songs can brighten your day for a few minutes, it was worth it.

— Tom Scholz

Rush and Wal-Mart?

I really don’t know what to think. . . .

Progarchy: 2013 in Review, A WordPress Report

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2013 annual report for this blog.

Here’s an excerpt:

The Louvre Museum has 8.5 million visitors per year. This blog was viewed about 88,000 times in 2013. If it were an exhibit at the Louvre Museum, it would take about 4 days for that many people to see it.

Last Stand of the Analog Kids

The digital future is here. Streaming is increasing and downloading is shrinking.

While the major record labels are floundering, Google is backing a small new new record label called “300” (named after the movie about the last stand of the Spartans at Thermopylae).

This reveals “that Google is prepared to invest in at least partially owning music copyrights and helping to develop artists outside of the traditional label system“:

- 300 will be “a music content company devoted to the discovery and development of the artists of the future.”

- The general idea is “to create an innovative artist development structure with greater flexibility and lower overheads to challenge the majors.”

- Other investment funds are involved in addition to Google, but Google is the biggest investor.

- … 300 “promises to push the envelope in terms of artist development and distribution.”

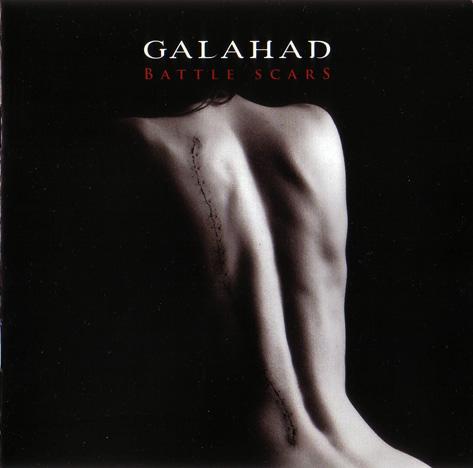

Seize the Day: Galahad, BATTLE SCARS

[N.B. Due to weather, our internet is out, and I’ve typed this and posted it using our cell connection. Spotty at best. If there are errors and typos in the post, please don’t let it reflect on all of progarchy. When I have a real connection, I’ll clean it up. Promise!–Brad, ed.]

I hate to admit it, but I didn’t know the music of Galahad until about a year and a half ago.

Alison Henderson, first lady of prog and a fellow progarchist, introduced me to the music at the time that Battle Scars (April 2012) came out. “Brad, you have to check out the new Galahad album. It’s brilliant.” Actually, I’m paraphrasing, not quoting. But, I bet I’m really close when remembering her email that day.

I never fail to follow the advice of Lady Henderson, and I downloaded the music that day.

From the opening plaintive words to the direct pleading lines of “Battle Scars, Battle Scars,” I was rather taken. I wrote back to her almost immediately, “This is what Ultravox should’ve been!” She replied that she would have to take my word for it.

Granted, I really dislike it when reviewers compare Big Big Train to Genesis, as though Genesis needed completing or as though Big Big Train exists to fill the void left by 1977 Genesis. So, please don’t take my comparison as anything more than a joyful comparison. Stu Nicholson’s voice has, in the best sense, a Midge Ure quality—bringing just the perfect amount of emotion and emphasis to a song. So, imagine if Ultravox had decided to explore the farthest reaches of its potential after releasing Rage in Eden (especially side 2 of that amazing work). Imagining such a beautiful thing, I can see—far into the distance—Battle Scars or Beyond the Realms of Euphoria.

After the brief discussion with Alison, being the obsessive prog fan that I’m sure many progarchists are, I looked up everything I could find regarding Galahad. I’d heard the name, many times, of course, before April 2012, but always in the context of “neo-prog.”

Neo-Progressive Rock

As much as I pride myself (always dangerous) on my knowledge of prog, ca. 1971 to the present, I’m really weak on what’s called “neo prog” or “second-wave prog.” At the time that second-wave prog emerged, my junior high, high school, and college years (Class of 1990), I was listening to so-called new wave such as Thomas Dolby, The Cure, and XTC, presuming them to be the rightful inheritors of Yes and Genesis. For me, the ultimate prog album of the 1980s is Talk Talk’s Spirit of Eden. Next to Talk Talk, Rush was my favorite band. I didn’t even know about Marillion until a friend introduced me to them in 1993. He handed me a copy of Misplaced Childhood, and I was stunned such a group had existed without my knowledge (there’s that pride again). I very much liked what I heard, but this was just before Brave, The Light, and The Flower King appeared—which almost completely stole my attention.

Needless to write at this point, my knowledge of Pallas, IQ, and Galahad—all supposed neo-prog—was pretty poor. About eight or nine years ago, I started collecting the back catalogues of Pallas and IQ, but Galahad still remained off my radar. I’m pretty much a complete “newbie” when it comes to other neo-prog artists.

I’m not sure if neo-prog is a sub-genre of progressive rock or really the “second wave of prog.” Whatever it is, I like what I’ve heard. . . .

Battle Scars

. . . . especially when it comes to Galahad. I like it very much. Indeed, this is an understatement. From the moment I first heard Battle Scars, I knew this was a band I would come to cherish. And, I have. Though I regret having missed out on so much since 1985 when it comes to this band, I’m also really happy to have it all to explore again. As I love to tell my students, I’m jealous that so many of them get to read The Lord of the Rings for the first time. I would give a lot for that “first time” again. I feel I’ve been given a gift by coming to Galahad late in life.

I really have no idea if Battle Scars is a “proper” neo-progressive album or not. I don’t have the tools to judge, and I’m more than content to know it’s brilliant music, whatever label might adhere to it.

In terms of tone, Battle Scars is the Grace Under Pressure of our present age In 1984, Rush explored—in a rather dour, harried, poetic fashion—the final days of the Cold War, though most of us didn’t know the days of the Soviet empire were numbered. Gulags, holocaust camps, the loss of a friend, fear, acid rain, and rabbits running under are squealing wheels all haunted Grace Under Pressure. Listening to this album while devouring various dystopian novels fundamentally shaped my perceptions of what I saw in the news.

With Battle Scars, Nicholson has equalled Peart in quality and tone, asking what a post-9/11, a post-Bush, world might mean. But, just as with Grace Under Pressure, the events of the world offer a symbol for the events of the soul. Disorder in one is disorder in the other.

The album opens with haunting words—even in delivery—of St. Paul. Do our actions reap corruption and death or life everlasting?

I’m not sure if Nicholson wants his listeners to take these words literally or not, but they fit ominously and perfectly, setting the stage for some of the most important and meaningful questions we can ever ask ourselves, Greek or Jew, male or female, bond or free.

How to you want to live in this world. With integrity and purpose or without? Do you want to achieve and strive or do you want to glide and get by? Do you want the message on your tombstone to read “he lived” or to read “he lived well”?

Though only seven tracks at 44 minutes, Battle Scars packs a serious punch. After the contemplative opening moments quoting St. Paul in hushed tones, Battle Scars becomes relentless. Indeed, a wave of strings and respectful vocals become pounding bass and drums, crying against vanity. “Hollow words count for nothing.”

An explosion or implosion ends the first track, and it glides into some nice reverb and more pounding bass, guitar, and drums in the shortest track of the album, “Reach for the Sun,” the lyrics reminding the listener that “battle scars are real.”

Track three, “Singularity,” begins with some appropriate spacey ethereal washes of keyboards, and the distant angular guitar is especially good. It breaks into a full rock song a little over a minute into the track, and the listener is propelled forward again. Having reached beyond the pain and suffering of this world, the protagonist of “Battle Scars” has transcended reality in his imagination and integrity. “You can’t touch me now.” The track ends with some beautiful, romantic piano.

“Bitter and Twisted,” track four, brings the listener back to the world, with every instrument back in full, driving play. It’s in this track that the band displays their full strength, as individual players and as an artistic whole. This is one very tight band. Lyrically, it’s difficult to know if Nicholson is identifying with the protagonist here, expressing shock at betrayal, or if we’re given the standpoint of an observer misperceiving and misunderstanding the protagonist. “You’re just a little piece of nothing at all.”

With track five, “Suspended Animation,” the protagonist identifies the evil that is in himself and the world around him. Here, we find a movement toward reconciling the order of the inward and outer person. The protagonist must reconcile his own troubles and problems, seeking some kind of forgiveness and atonement. Another driving rock song. Nicholson’s vocals are particularly good, especially as he proclaims and enunciates the words, “suspended animation.”

My favorite song on the album is the sixth, “Beyond the Barbed Wire.” As one would expect with such a title, the song is not a happy one, though it might be a resigned one. One of the quieter songs on the album, at least for its first minute or so, it reminds the listener that though the Nazis and Soviets might be gone, other evils remain in the world. At least, as I’m understanding the lyrics, this is what I’m hearing. The holocausts and gulags have just taken on new shape and new form, but the essence of such evils remains. “I’m just thinking, just thinking, beyond the barbed wire.” The protagonist, however, finds great strength in those who came before him.

The spirits of the lost reinforce my will

Their souls reunite in pure defiance

We will not disappear in mournful smoke.

This is a stunningly beautiful lyric, and Nicholson delivers it not just ably, but expertly. The voice reminds the listener of the opening lines of the album, the words from Paul.

The final song, “Seize the Day,” is the longest track and it successfully ties the whole work together, allowing all to end in real joy. The track also prepares the listener for the second Galahad release of the 2012, Beyond the Realms of Euphoria. Still very much a rock song, “Seize the Day,” also embraces, very well, forms of electronica. “Seize the day/relish every moment.”

Thank you, Stu, Roy, Spencer, Dean, and Neil. You have created a thing of beauty. Long may the creativity and virtue of Galahad continue.

The Winery Dogs (Best of 2013 — Part 10)

Coming in the #10 slot (in alphabetical order) on my Best of 2013 list is this supergroup’s eponymous bolt of lightning:

The Winery Dogs

Wow. This album blew me away.

One of my all-time favorite prog drummers, Mike Portnoy, teamed up with Richie Kotzen and Billy Sheehan this year, and they demonstrate to us all the unbeatable power of the power trio when it is done right.

The thrill of listening to these catchy songs, and to the virtuoso musical chops on display in them, evoked a lot of happy musical memories of musical “first encounters” for me.

First, there is the rush of listening to Rush. Like I say, there is nothing quite as exciting as the hard rock power of the power trio when it is done right. The Winery Dogs evoke for me the musical joy I experienced when first listening to Rush in high school. Of course, the greatness of Rush is still there to be savored with every listen. But there is nothing quite like the first ten times that you listen to a truly great album. With this release from The Winery Dogs, we get to experience that kind of magic again, as for the first time.

Second, there is the sonic adrenaline that I love to tap into by listening to Chris Cornell and Audioslave. Therefore I am dedicating my Winery Dogs nomination here for the Best of 2013 to Carl, my fellow Soundgarden aficionado in the republic of Progarchy, in case he has not heard it yet. It’s remarkably satisfying, for those of us who can’t get enough of such upper-echelon vocal stylings, how well Richie Kotzen can recreate the thrill of listening to Chris Cornell.

Third, there is the undefinable excitement that skilled musicianship can bring to enhance and elevate any genre’s tropes. Suddenly, as you round what seems to be a familiar musical corner, you are blindsided and pleasantly surprised by an unexpected display of virtuosity that showers you with musical grace. When Billy Sheehan works his otherworldly magic here on bass guitar, or when Richie Kotzen transports us into ordinarily inaccessible dimensions of guitarcraft, or when Mike Portnoy muscles his way out of the speakers and right into the room next to you, I am reminded of those magical younger days when my friends and I first began listening to all those great, lesser-known albums by “musicians’ musicians.” Those discs opened up musical pathways that most of our schoolmates were missing out on. For some reason, when listening to The Winery Dogs, memories of listening to The Steve Morse Band come to mind for me. But each of you will find that your own personal memories of your first listens to “the greats” will be evoked by this album’s dazzling display of virtuosity.

Best of all, this album is a perfect cure for the dragon sickness of any nascent prog tendency to become a tribal, self-enclosed musical world. It makes the joy of music available to anyone with the ears to listen.

This disc is a perfect illustration of how musical men with prog chops can quite simply put their musical skills in the noble service of simply rocking out. Anyone with a heart can relate to this cause. I invite you to happily endorse it with the simplest of gestures, like a fist pump or an air guitar solo.

Rock on, gentlemen.