If in May 1972 the Rolling Stones defined and deified rock and roll (and themselves) with the release of Exile on Main Street, one month later Roxy Music’s debut album made splatter art of such ideas. A galvanizing, glammed-out, punked-up masterpiece, Roxy Music is the first of a series of four albums (including For Your Pleasure, Stranded, and Country Life) that artfully engage a European, distinctly non-bluesy, approach to rock. Where a mere three years later Roxy would hit the disco with “Love is the Drug” and a decade on would make one of the great, soulful, chilled-out new wave records with Avalon, in 1972 the band was pushing in every direction, its self-defined non-musician Brian Eno creating on-the-fly soundscapes that turned Andy Mackay’s reeds into guitars and Phil Manzanera’s guitars into sirens, while Bryan Ferry ululated — more in the style of Roger Chapman than the smooth crooner he would become — loose, even free associative, lyrics rendered on a spectrum from oddball to heartbreaking. While their image and aesthetic fit into the cutting edge of the British glam music scene at the time (Bowie’s Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust was released just the week before), and their creation myth is inseparable from their influential visual audacity (for who could look more creepy in a feather boa and leopard skin than the be-rouged Eno?), it was the band’s intense musicianship and penchant for the melodic that was the core of its success and influence, and why you can hear this first album in everything from The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Talking Heads. The sound is richly subversive, hooks are everywhere, songs use shifting dynamics to create emotional peaks. They challenge convention, but are fully wrought, they are all surface, but go deep.

If in May 1972 the Rolling Stones defined and deified rock and roll (and themselves) with the release of Exile on Main Street, one month later Roxy Music’s debut album made splatter art of such ideas. A galvanizing, glammed-out, punked-up masterpiece, Roxy Music is the first of a series of four albums (including For Your Pleasure, Stranded, and Country Life) that artfully engage a European, distinctly non-bluesy, approach to rock. Where a mere three years later Roxy would hit the disco with “Love is the Drug” and a decade on would make one of the great, soulful, chilled-out new wave records with Avalon, in 1972 the band was pushing in every direction, its self-defined non-musician Brian Eno creating on-the-fly soundscapes that turned Andy Mackay’s reeds into guitars and Phil Manzanera’s guitars into sirens, while Bryan Ferry ululated — more in the style of Roger Chapman than the smooth crooner he would become — loose, even free associative, lyrics rendered on a spectrum from oddball to heartbreaking. While their image and aesthetic fit into the cutting edge of the British glam music scene at the time (Bowie’s Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust was released just the week before), and their creation myth is inseparable from their influential visual audacity (for who could look more creepy in a feather boa and leopard skin than the be-rouged Eno?), it was the band’s intense musicianship and penchant for the melodic that was the core of its success and influence, and why you can hear this first album in everything from The Rocky Horror Picture Show to Talking Heads. The sound is richly subversive, hooks are everywhere, songs use shifting dynamics to create emotional peaks. They challenge convention, but are fully wrought, they are all surface, but go deep.

Tag: soundstreamsunday

soundstreamsunday: “Stop Breaking Down” by the Rolling Stones

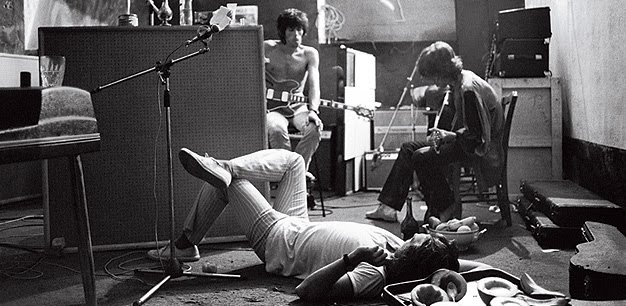

“Unlikely” is probably the right word, that the hairiest, grittiest, straight-uppenest American rock record of the 1970s, maybe ever, would be made by an English band in tax exile in the south of France lolling in sheer European decadence. That the Rolling Stones attained such a state of grace is only partly surprising, though, given the sheer will of their progress to the point of Exile on Main Street: with Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, and Sticky Fingers the writing was on the wall, but it was this double album that sealed their legend, where the channeling was complete, where without seams the Deep South blackness poured through their pasty, pale, drug-addled limey fingers in drums and basses and guitars and voxes and keys and horns. They hadn’t just gone to the crossroads, they’d set up the tent years before and waited it out, for the spirit to finally visit them. “Satisfaction”? “Get Off My Cloud”? Even “Honky Tonk Women,” with its perfect guitar? Those were killing time, chop builders, and the work they’ve done since has had high points too but has never been more than the downhill coast. Exile’s the big meet up, a meticulously made album with no contrivance, a blues turned over with a rock shovel, originals mixing with covers with barely a hint of borderline, as if this is their music as much as it is yours or mine or Robert Johnson’s. And it’s here that they cover one of Johnson’s more unusual songs, less a blues than a prophet’s vision of the rock and roll to come. The Stones had already covered Johnson on record by the time of Exile — the down tempo “Love in Vain” was featured on Let It Bleed — but the rock and roll suggested in “Stop Breaking Down” is wrung from the song by the Stones, matching the strut of the lyric, “Every time I’m walking down the street….”

“Unlikely” is probably the right word, that the hairiest, grittiest, straight-uppenest American rock record of the 1970s, maybe ever, would be made by an English band in tax exile in the south of France lolling in sheer European decadence. That the Rolling Stones attained such a state of grace is only partly surprising, though, given the sheer will of their progress to the point of Exile on Main Street: with Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, and Sticky Fingers the writing was on the wall, but it was this double album that sealed their legend, where the channeling was complete, where without seams the Deep South blackness poured through their pasty, pale, drug-addled limey fingers in drums and basses and guitars and voxes and keys and horns. They hadn’t just gone to the crossroads, they’d set up the tent years before and waited it out, for the spirit to finally visit them. “Satisfaction”? “Get Off My Cloud”? Even “Honky Tonk Women,” with its perfect guitar? Those were killing time, chop builders, and the work they’ve done since has had high points too but has never been more than the downhill coast. Exile’s the big meet up, a meticulously made album with no contrivance, a blues turned over with a rock shovel, originals mixing with covers with barely a hint of borderline, as if this is their music as much as it is yours or mine or Robert Johnson’s. And it’s here that they cover one of Johnson’s more unusual songs, less a blues than a prophet’s vision of the rock and roll to come. The Stones had already covered Johnson on record by the time of Exile — the down tempo “Love in Vain” was featured on Let It Bleed — but the rock and roll suggested in “Stop Breaking Down” is wrung from the song by the Stones, matching the strut of the lyric, “Every time I’m walking down the street….”

soundstreamsunday: “Traveling Riverside Blues” by Robert Johnson

On the heels of Benny Goodman’s concert at Carnegie Hall in January 1938, promoter/producer John Hammond (Billie Holliday, Bessie Smith, Count Basie, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Ray Vaughan…unbelievable) conceived of a concert that would further acknowledge the debt American music owed its roots, within the hallowed walls of the Hall. Race relations being what they were, so risky was Hammond’s venture that it took the American Communist Party to finance the show. “From Spirituals to Swing” showcased, along again with Goodman and Basie, blues and boogie artists like Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry, Big Joe Turner, Helen Humes, James P. Johnson, and Meade Lux Lewis. Absent, although invited by Hammond, was Robert Johnson, an obscure Delta blues guitarist and singer who had been getting some buzz via a minor regional hit called “Terraplane Blues.” Hammond came to learn that Johnson had been murdered that summer, and replaced Johnson with Broonzy, and for all of Broonzy’s subsequent influence on the blues revival of the 1960s, it would be Robert Johnson whose legend would grow (particularly after Hammond et al. produced the first compilation of Johnson’s work in 1960), a ubiquitous ghost, as the bluesman who sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads in exchange for a phenomenal talent. This perception of Johnson may have actually originated with him, and songs like “Hellhound on My Trail, “Me and the Devil Blues,” and “Crossroads Blues,” don’t dispel the self-made myth; yet Johnson’s talent speaks to years of real work, occupying a liminal space in an environment hostile to almost everything he was, and equating this with a meeting with Satan at the crossroads isn’t a stretch: how much would you sacrifice to be the best at the thing you love the most? Johnson gave it his life; what might have appeared from the outside, by those who knew him, as supreme self-involvement that transcended any sustained relationships, and led to his poisoning at the hands of a lover’s jealous husband, was the ultimate tribute to his own self-made gift. He had more to get done on this earth than most, and that had to be a kind of hell as well as a kind of ecstasy. You can hear both in every one of his 42 existing recordings. And the “centennial edition” issued in 2011 offers the set with noise reduction deftly applied, so that the surface pops and scratches from the original master discs are scrubbed without loss or distortion of content. You can hear Johnson shifting in his chair, and, in the length of echoes, the subtle changes in his position relative to the corner that he faced while recording — he is made human, and what he produces in that corner, alone with his guitar, is all the more remarkable. Johnson’s technical ability allowed him to play a rhythm and a lead simultaneously, but while much has been made of his guitar playing, and his odd and varied tunings, he used his voice to equal effect, in service to his songs, here a vibrato, there a growl, here a moan or high-pitched yawp. He employed a handful of templates for many of his songs, but brought to them a loose approach and lyrical dexterity. There is also a strong sense of performance in the tunes. Where Charley Patton was screaming and hollering his blues, and Blind Willie Johnson may have been truly possessed, Robert Johnson was the first post-Delta blues singer, a polished showman using affectation in an almost punk-ish way. It is maybe this that caught the attention of Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Billy Gibbons, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton — who had the nerve, in one form or another, to take on Johnson’s “Stop Breaking Down,” “Sweet Home Chicago,” “Come on in My Kitchen,” “Ramblin’ on My Mind,” “Traveling Riverside Blues,” “Dust My Broom,” “Four Until Late,” “Crossroads Blues,” “Love in Vain” — and what made it even conceivable that such songs could be covered or transformed or influential. Because in a sense Johnson was covering them himself, replaying that ride to the crossroads. Choosing the trip, feeling the night. It is the essence of all rock and roll.

On the heels of Benny Goodman’s concert at Carnegie Hall in January 1938, promoter/producer John Hammond (Billie Holliday, Bessie Smith, Count Basie, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Ray Vaughan…unbelievable) conceived of a concert that would further acknowledge the debt American music owed its roots, within the hallowed walls of the Hall. Race relations being what they were, so risky was Hammond’s venture that it took the American Communist Party to finance the show. “From Spirituals to Swing” showcased, along again with Goodman and Basie, blues and boogie artists like Big Bill Broonzy, Sonny Terry, Big Joe Turner, Helen Humes, James P. Johnson, and Meade Lux Lewis. Absent, although invited by Hammond, was Robert Johnson, an obscure Delta blues guitarist and singer who had been getting some buzz via a minor regional hit called “Terraplane Blues.” Hammond came to learn that Johnson had been murdered that summer, and replaced Johnson with Broonzy, and for all of Broonzy’s subsequent influence on the blues revival of the 1960s, it would be Robert Johnson whose legend would grow (particularly after Hammond et al. produced the first compilation of Johnson’s work in 1960), a ubiquitous ghost, as the bluesman who sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads in exchange for a phenomenal talent. This perception of Johnson may have actually originated with him, and songs like “Hellhound on My Trail, “Me and the Devil Blues,” and “Crossroads Blues,” don’t dispel the self-made myth; yet Johnson’s talent speaks to years of real work, occupying a liminal space in an environment hostile to almost everything he was, and equating this with a meeting with Satan at the crossroads isn’t a stretch: how much would you sacrifice to be the best at the thing you love the most? Johnson gave it his life; what might have appeared from the outside, by those who knew him, as supreme self-involvement that transcended any sustained relationships, and led to his poisoning at the hands of a lover’s jealous husband, was the ultimate tribute to his own self-made gift. He had more to get done on this earth than most, and that had to be a kind of hell as well as a kind of ecstasy. You can hear both in every one of his 42 existing recordings. And the “centennial edition” issued in 2011 offers the set with noise reduction deftly applied, so that the surface pops and scratches from the original master discs are scrubbed without loss or distortion of content. You can hear Johnson shifting in his chair, and, in the length of echoes, the subtle changes in his position relative to the corner that he faced while recording — he is made human, and what he produces in that corner, alone with his guitar, is all the more remarkable. Johnson’s technical ability allowed him to play a rhythm and a lead simultaneously, but while much has been made of his guitar playing, and his odd and varied tunings, he used his voice to equal effect, in service to his songs, here a vibrato, there a growl, here a moan or high-pitched yawp. He employed a handful of templates for many of his songs, but brought to them a loose approach and lyrical dexterity. There is also a strong sense of performance in the tunes. Where Charley Patton was screaming and hollering his blues, and Blind Willie Johnson may have been truly possessed, Robert Johnson was the first post-Delta blues singer, a polished showman using affectation in an almost punk-ish way. It is maybe this that caught the attention of Bob Dylan, Keith Richards, Billy Gibbons, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton — who had the nerve, in one form or another, to take on Johnson’s “Stop Breaking Down,” “Sweet Home Chicago,” “Come on in My Kitchen,” “Ramblin’ on My Mind,” “Traveling Riverside Blues,” “Dust My Broom,” “Four Until Late,” “Crossroads Blues,” “Love in Vain” — and what made it even conceivable that such songs could be covered or transformed or influential. Because in a sense Johnson was covering them himself, replaying that ride to the crossroads. Choosing the trip, feeling the night. It is the essence of all rock and roll.

soundstreamsunday: “Sing Sing Sing” by Benny Goodman

The Benny Goodman Orchestra’s performance at Carnegie Hall in January 1938 has a place in history as the coming out party for jazz, a legitimizing of an art form within the fortress of American (read: white/European) highbrow music. Ripe for irony? Yes. But when we recall this was the era of “race” records, and that jazz in the white American psyche was still an odd conflation of jump-and-jive black culture, blackface minstrelsy, and the carefully staged musical numbers of Hollywood sophisticates, Goodman and company’s triumph was quite real. Bringing an integrated group of musicians that included the best of its day to Carnegie Hall, blowing the collective Depression-era Jim Crow “high culture” hive-mind…. remarkable. This music is fierce, sometimes nasty, less a nod to propriety than a tuxedo-ed finger in the eye, dashing racial and artistic division by sheer force of celebratory musicality. “Sing Sing Sing,” a Goodman Orchestra signature tune written by Louis Prima, was the band’s finale, clocking in at over 12 minutes, and thus recorded, using the technology of the time, on acetate discs using a relay of multiple turntables (while the concert was almost instantly legendary, the recordings wouldn’t be made available for over a decade: see http://www.jitterbuzz.com/carcon.html for the whole fascinating story). The centerpiece of the song is Gene Krupa’s drumming, fading in and out of the mix — which was performed by the musicians rather than by the engineers — and ultimately making him jazz (and, by association, rock) drumming’s first real star. Lithe, articulate solos by Goodman, Harry James, and Jess Stacy shift dynamics, riding over Krupa’s pounding, roiling the waves sent up by the Orchestra. Even if you haven’t heard this song, you’ve heard it. But…get lost in it.

The Benny Goodman Orchestra’s performance at Carnegie Hall in January 1938 has a place in history as the coming out party for jazz, a legitimizing of an art form within the fortress of American (read: white/European) highbrow music. Ripe for irony? Yes. But when we recall this was the era of “race” records, and that jazz in the white American psyche was still an odd conflation of jump-and-jive black culture, blackface minstrelsy, and the carefully staged musical numbers of Hollywood sophisticates, Goodman and company’s triumph was quite real. Bringing an integrated group of musicians that included the best of its day to Carnegie Hall, blowing the collective Depression-era Jim Crow “high culture” hive-mind…. remarkable. This music is fierce, sometimes nasty, less a nod to propriety than a tuxedo-ed finger in the eye, dashing racial and artistic division by sheer force of celebratory musicality. “Sing Sing Sing,” a Goodman Orchestra signature tune written by Louis Prima, was the band’s finale, clocking in at over 12 minutes, and thus recorded, using the technology of the time, on acetate discs using a relay of multiple turntables (while the concert was almost instantly legendary, the recordings wouldn’t be made available for over a decade: see http://www.jitterbuzz.com/carcon.html for the whole fascinating story). The centerpiece of the song is Gene Krupa’s drumming, fading in and out of the mix — which was performed by the musicians rather than by the engineers — and ultimately making him jazz (and, by association, rock) drumming’s first real star. Lithe, articulate solos by Goodman, Harry James, and Jess Stacy shift dynamics, riding over Krupa’s pounding, roiling the waves sent up by the Orchestra. Even if you haven’t heard this song, you’ve heard it. But…get lost in it.

soundstreamsunday: “Futureworld” by Trans Am

The relentlessness of TransAm’s album Futureworld is a darkly beautiful thing, a fist-waving ode to personal alienation in the late 90. Its Germanic vocoder nods to Kraftwerk, its post-rock distortion and, above all, Sebastian Thomson’s drumming, set a tone so consistently, yet energetically, brooding that it simply will not be denied. It fits neatly in the set of movies and music (thinking Fight Club, Boards of Canada…) directly pre-9/11 that captures the crumbling of 90s tech optimism, the cold distance occasioned by staring at a screen rather than reading a person’s face. This is where the digital shit hits the fan. When I listen to the song “Futureworld” I think these things and I also rock out. Its structure is all about the dynamics of momentum, its breakneck launch ending as a ship with rockets disengaged, a pulse along a motherboard, an incredible downshift punctuated by unlikely but perfect Bonham-esque pounding.

The relentlessness of TransAm’s album Futureworld is a darkly beautiful thing, a fist-waving ode to personal alienation in the late 90. Its Germanic vocoder nods to Kraftwerk, its post-rock distortion and, above all, Sebastian Thomson’s drumming, set a tone so consistently, yet energetically, brooding that it simply will not be denied. It fits neatly in the set of movies and music (thinking Fight Club, Boards of Canada…) directly pre-9/11 that captures the crumbling of 90s tech optimism, the cold distance occasioned by staring at a screen rather than reading a person’s face. This is where the digital shit hits the fan. When I listen to the song “Futureworld” I think these things and I also rock out. Its structure is all about the dynamics of momentum, its breakneck launch ending as a ship with rockets disengaged, a pulse along a motherboard, an incredible downshift punctuated by unlikely but perfect Bonham-esque pounding.

Soundstreamsunday: “Gravity’s Angel” by Laurie Anderson

Progressive rock’s avant garde wing has always acted as a kind of disciplined version of its more mainstream cousin, dependent on self-imposed constraints, those kinds of “oblique strategies” that Brian Eno and his expanding circle of collaborators employed to spur, and rein in, their impulses. The cross-pollination of these two (sometimes warring) factions — at least as that dichotomy might have been posed by critics — was most evident in the 1970s, and was particularly expressed in the Venn diagram that was Roxy Music and King Crimson, the kind of built-in tension that ultimately made Eno and Fripp’s projects guilty of indulgence — often too smart for their own good — but also wildly interesting. Within this world landed Laurie Anderson, a New York-based performance artist whose albums in the 80s employed many of the aforementioned Eno/Crimson cast of characters (in addition to the No Wave artists Eno became associated with), and whose songs, due to their melodic charm, could work their way into the popular consciousness to such a degree that rare was the record collection by decade’s end that — if it included a Talking Heads or Belew-era Crimson album — didn’t include at least one of her works. Her influence is inestimable. “Gravity’s Angel” is from the album Mister Heartbreak, and captures her sound and approach: a partiality to electronic instruments, experimentation abetted by first-class Crimon-ish musos (Adrian Belew, Bill Laswell, Peter Gabriel), and an emphasis on finding a relief of humanity against a plane that could be coldly distant, i.e., exploring the human condition in the late 20th century. My understanding via Wikipedia is that she asked Thomas Pynchon if she could musical-ize Gravity’s Rainbow, and he replied, well, yes, if she could do so with only a banjo. That didn’t happen, but this did:

Progressive rock’s avant garde wing has always acted as a kind of disciplined version of its more mainstream cousin, dependent on self-imposed constraints, those kinds of “oblique strategies” that Brian Eno and his expanding circle of collaborators employed to spur, and rein in, their impulses. The cross-pollination of these two (sometimes warring) factions — at least as that dichotomy might have been posed by critics — was most evident in the 1970s, and was particularly expressed in the Venn diagram that was Roxy Music and King Crimson, the kind of built-in tension that ultimately made Eno and Fripp’s projects guilty of indulgence — often too smart for their own good — but also wildly interesting. Within this world landed Laurie Anderson, a New York-based performance artist whose albums in the 80s employed many of the aforementioned Eno/Crimson cast of characters (in addition to the No Wave artists Eno became associated with), and whose songs, due to their melodic charm, could work their way into the popular consciousness to such a degree that rare was the record collection by decade’s end that — if it included a Talking Heads or Belew-era Crimson album — didn’t include at least one of her works. Her influence is inestimable. “Gravity’s Angel” is from the album Mister Heartbreak, and captures her sound and approach: a partiality to electronic instruments, experimentation abetted by first-class Crimon-ish musos (Adrian Belew, Bill Laswell, Peter Gabriel), and an emphasis on finding a relief of humanity against a plane that could be coldly distant, i.e., exploring the human condition in the late 20th century. My understanding via Wikipedia is that she asked Thomas Pynchon if she could musical-ize Gravity’s Rainbow, and he replied, well, yes, if she could do so with only a banjo. That didn’t happen, but this did:

soundstreamsunday: “Live at BRIC” by Esperanza Spalding

There may be too much to say about and too much going on in Esperanza Spalding’s new album, Emily’s D+Evolution, to relate anything meaningful in writing here. “Live at BRIC,” a performance of songs from the album, was recorded by NPR in March, and it shines brightly, landing it’s Parliament-like Mothership on planets traveled by Joni Mitchell, King Crimson, Zappa. Importantly, it throws down the gauntlet in terms of prog rock performance, making more out of less. It’s not just a bunch of musos looking at the floor in their noodle space, but the simple theatricality complements the music without getting in the way — it’s emotional, engaged, a pure and honest expression.

There may be too much to say about and too much going on in Esperanza Spalding’s new album, Emily’s D+Evolution, to relate anything meaningful in writing here. “Live at BRIC,” a performance of songs from the album, was recorded by NPR in March, and it shines brightly, landing it’s Parliament-like Mothership on planets traveled by Joni Mitchell, King Crimson, Zappa. Importantly, it throws down the gauntlet in terms of prog rock performance, making more out of less. It’s not just a bunch of musos looking at the floor in their noodle space, but the simple theatricality complements the music without getting in the way — it’s emotional, engaged, a pure and honest expression.

Soundstream Sunday: “Impressions Of My Country / Foothill Patrol” by Gabor Szabo

…the next move, after Manuel Gottsching’s E2-E4, pulls the thread of that piece’s guitar work and comes up with Gabor Szabo at his funky six-string best, in Stockholm in 1972. From the album Small World (available as a compilation with its sister album, Belsta River, as In Stockholm), “Impressions Of My Country / Foothill Patrol” is a duel with Janne Schaffer — a Swedish guitar hero known mostly for his work with Abba. In 1972 Szabo, a serious jazz cat with a penchant for interpreting pop tunes (and riding that line between elevator music and the sublime), might have been primed to explore this Hendrixian territory. The previous year his “Gypsy Queen,” from the album Spellbinder (Impulse, 1966), had been adapted to round out Santana’s cover of “Black Magic Woman” on the album Abraxas. That song reached number four on the charts, while Abraxas went to number one. Szabo’s approach on Small World may have been, in no small part, influenced by Santana. The usually clean tones are fuzzed out, wah-wah pedals are employed, and there is a freer, funkier feel to the proceedings. Coming from Szabo, though, it’s no surprise, and his experimentation with tone and feedback in the 60s, coupled with the use of his native eastern European melodies, helped define a psychedelic sensibility that lent itself to the jam.

…the next move, after Manuel Gottsching’s E2-E4, pulls the thread of that piece’s guitar work and comes up with Gabor Szabo at his funky six-string best, in Stockholm in 1972. From the album Small World (available as a compilation with its sister album, Belsta River, as In Stockholm), “Impressions Of My Country / Foothill Patrol” is a duel with Janne Schaffer — a Swedish guitar hero known mostly for his work with Abba. In 1972 Szabo, a serious jazz cat with a penchant for interpreting pop tunes (and riding that line between elevator music and the sublime), might have been primed to explore this Hendrixian territory. The previous year his “Gypsy Queen,” from the album Spellbinder (Impulse, 1966), had been adapted to round out Santana’s cover of “Black Magic Woman” on the album Abraxas. That song reached number four on the charts, while Abraxas went to number one. Szabo’s approach on Small World may have been, in no small part, influenced by Santana. The usually clean tones are fuzzed out, wah-wah pedals are employed, and there is a freer, funkier feel to the proceedings. Coming from Szabo, though, it’s no surprise, and his experimentation with tone and feedback in the 60s, coupled with the use of his native eastern European melodies, helped define a psychedelic sensibility that lent itself to the jam.

soundstreamsunday: “E2-E4” by Manuel Göttsching

Manuel Göttsching was the guitarist for Ash Ra Tempel, a formative krautrock space jam band based in Berlin that included Klaus Schulze (post-Tangerine Dream/pre-solo) and Hartmut Enke. Göttsching made E2-E4 in 1981, years after Ash Ra’s heyday, as something to listen to on a plane trip. It became, upon its release in 1984, a classic of electronic house/dance and trance music, and is the natural descendant of Göttsching’s Inventions for Electric Guitar (1975). The piece is divided into tracks on CD but plays seemlessly across an hour as an integrated suite. Göttsching holds off on soloing for over 30 minutes, and when he let’s go it’s with the restraint of a jazz player. I’ve listened to this record maybe a dozen times over the last 20 years, so not a lot, but would never relinquish it. I have an idea that music like this (what Julian Cope might term “motorik”), when it’s at its best, can work like noise-cancelling headphones, as if by tapping into the wavelength of your brain’s “always on” subchannel it can then mirror and bring the mind’s noise to zero sum, creating a kind of peace not to be had elsewhere. Perhaps that’s a stretch, but, being in the deep with E2 E4, the background of the morning takes on a different kind of flow and light. Now, perhaps, a game of chess….

Manuel Göttsching was the guitarist for Ash Ra Tempel, a formative krautrock space jam band based in Berlin that included Klaus Schulze (post-Tangerine Dream/pre-solo) and Hartmut Enke. Göttsching made E2-E4 in 1981, years after Ash Ra’s heyday, as something to listen to on a plane trip. It became, upon its release in 1984, a classic of electronic house/dance and trance music, and is the natural descendant of Göttsching’s Inventions for Electric Guitar (1975). The piece is divided into tracks on CD but plays seemlessly across an hour as an integrated suite. Göttsching holds off on soloing for over 30 minutes, and when he let’s go it’s with the restraint of a jazz player. I’ve listened to this record maybe a dozen times over the last 20 years, so not a lot, but would never relinquish it. I have an idea that music like this (what Julian Cope might term “motorik”), when it’s at its best, can work like noise-cancelling headphones, as if by tapping into the wavelength of your brain’s “always on” subchannel it can then mirror and bring the mind’s noise to zero sum, creating a kind of peace not to be had elsewhere. Perhaps that’s a stretch, but, being in the deep with E2 E4, the background of the morning takes on a different kind of flow and light. Now, perhaps, a game of chess….

soundstreamsunday: Sonnenblumenstahl by Ulrich Schnauss and Jonas Munk

I’m continuing with my Jonas Munk kick from two weeks ago, when I posted the fabulous Sun River stream, “Esperanza Villanueva”. “Sonnenblumenstahl” is a beautiful piece of Moebius/Roedelius/Plank-style krautrock from Munk’s and Ulrich Schnauss’s highly recommended 2011 full-length collaboration. Munk the guitarist and Schnauss the keyboardist have both left their influential mark on ambient techno, and together they make music that is generous, melodic, and open, combining the best of both their musics. This song could be from Cluster’s Sowiesoso (or Zuckerzeit, OR Grosses Wasser), but has a character uniquely its own.

I’m continuing with my Jonas Munk kick from two weeks ago, when I posted the fabulous Sun River stream, “Esperanza Villanueva”. “Sonnenblumenstahl” is a beautiful piece of Moebius/Roedelius/Plank-style krautrock from Munk’s and Ulrich Schnauss’s highly recommended 2011 full-length collaboration. Munk the guitarist and Schnauss the keyboardist have both left their influential mark on ambient techno, and together they make music that is generous, melodic, and open, combining the best of both their musics. This song could be from Cluster’s Sowiesoso (or Zuckerzeit, OR Grosses Wasser), but has a character uniquely its own.