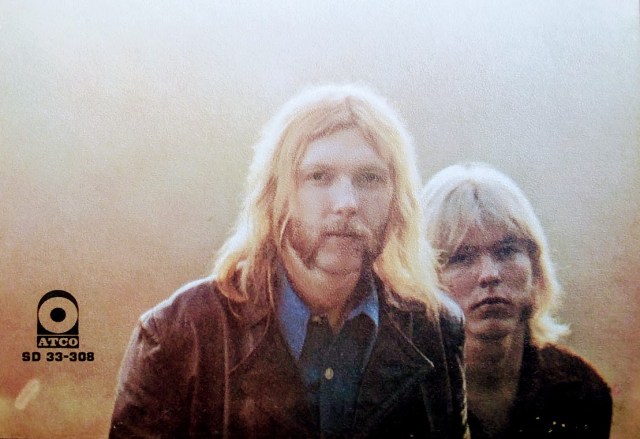

Southern Rock’s manifesto is like no other rock album. The Allman Brothers Band, released in November 1969, carries a hard sonic power absent from its closest temporal and spiritual brother, the Band’s Music from Big Pink (1968), and tight, sharp-cornered riffing missing from the work of the Grateful Dead, who the Allmans resembled in their two-drummer, double guitar form and in their tendency to stretch out in live performance. Mostly, though, the group had the brothers themselves: Duane, a guitar sharpshooter whose session work had honed his chops — including a wicked slide technique — to a razor’s edge; and Gregg, whose organ playing and lyric writing demonstrated a finesse far beyond his 21 years, and whose voice was a soulful, ragged howl coming from a place of honest truth. In an era when the integrity of white blues bands was, rightfully, beginning to be questioned, along with the plantation politics of the music industry, no one, not even Lester Bangs, argued with the Allman Brothers Band’s authenticity or the singular chords they struck, as they effortlessly crossed over into country and jazz, articulating a maturing musical vision for the American South. That they were an integrated band was interesting (in 1969 much of Georgia, the Allman’s home base, still segregated its schools), but it was what underpinned that fact that made their music ascend: a fascination with next steps, set against a background of a changing rock vocabulary, so that every member of the band was important. While Duane and Gregg receive much of the attention as the band’s geniuses (and they were), guitarist Dickey Betts’s influence on the band, particularly his use of the major pentatonic scale, went a long way towards defining the Southern Rock sound, while the rhythm section of Berry Oakley, Jai Johanny Johanson, and Butch Trucks provided a propulsive force but also a lithe one, booty shaking, more akin to what Carlos Santana was putting together on the west coast than anything coming out of the blues or country scenes of the time.

Southern Rock’s manifesto is like no other rock album. The Allman Brothers Band, released in November 1969, carries a hard sonic power absent from its closest temporal and spiritual brother, the Band’s Music from Big Pink (1968), and tight, sharp-cornered riffing missing from the work of the Grateful Dead, who the Allmans resembled in their two-drummer, double guitar form and in their tendency to stretch out in live performance. Mostly, though, the group had the brothers themselves: Duane, a guitar sharpshooter whose session work had honed his chops — including a wicked slide technique — to a razor’s edge; and Gregg, whose organ playing and lyric writing demonstrated a finesse far beyond his 21 years, and whose voice was a soulful, ragged howl coming from a place of honest truth. In an era when the integrity of white blues bands was, rightfully, beginning to be questioned, along with the plantation politics of the music industry, no one, not even Lester Bangs, argued with the Allman Brothers Band’s authenticity or the singular chords they struck, as they effortlessly crossed over into country and jazz, articulating a maturing musical vision for the American South. That they were an integrated band was interesting (in 1969 much of Georgia, the Allman’s home base, still segregated its schools), but it was what underpinned that fact that made their music ascend: a fascination with next steps, set against a background of a changing rock vocabulary, so that every member of the band was important. While Duane and Gregg receive much of the attention as the band’s geniuses (and they were), guitarist Dickey Betts’s influence on the band, particularly his use of the major pentatonic scale, went a long way towards defining the Southern Rock sound, while the rhythm section of Berry Oakley, Jai Johanny Johanson, and Butch Trucks provided a propulsive force but also a lithe one, booty shaking, more akin to what Carlos Santana was putting together on the west coast than anything coming out of the blues or country scenes of the time.

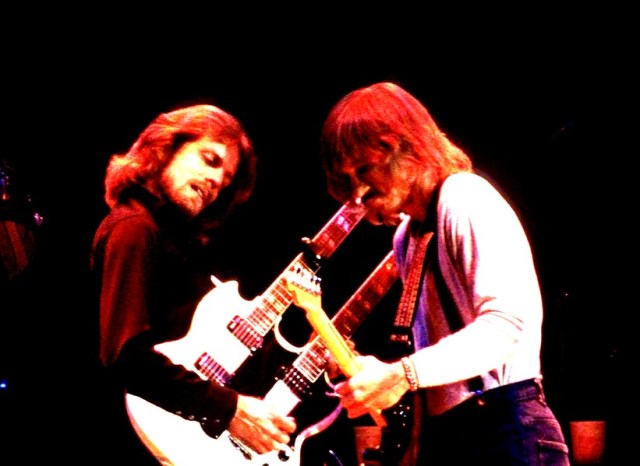

Paraphrasing the Rolling Stone Record Guide‘s review of the Allman’s Live at Fillmore East (1971), even when the band went long form, when they jammed, there weren’t any wasted notes. At a scant 33 minutes, the Allmans’ first album is similarly lean, a killer hard rock set that proved to be less of a template than an opening salvo (1970’s Idlewild South shows voracious growth, as does 1972’s Eat a Peach, Duane’s death notwithstanding). While “Dreams” and “Whipping Post” are the album’s jaw-dropping closers, this is a record with no filler whatsoever. “Every Hungry Woman” is a favorite, metal crunch up against slide guitar sirens, organ moans, and an epic swamp beast of a riff. The dueling guitars in the solo section say more in their few seconds than many bands say across a career, and Gregg’s roar channels some deep beast that must’ve drunk from the same watering hold as Ray Charles and Charley Patton. Inimitable.

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section.

On the other side of the 70s country rock that made the

On the other side of the 70s country rock that made the  The dark end of late 70s rock culture makes for strange bedfellows on the weekly infinite linear mixtape. One week after

The dark end of late 70s rock culture makes for strange bedfellows on the weekly infinite linear mixtape. One week after  Released in September 1979, Unleashed in the East, recorded on the Japanese leg of their Hell Bent for Leather tour, capped Judas Priest’s first long and storied decade, six months before their mainstream breakthrough British Steel. It’s a killer set, brightly produced, and enlivened some of their early material, which could tend towards studio stiffness. It was itself partly a studio effort, as singer Rob Halford had to add vocals after the fact, but anyone who loves this band or live records in general couldn’t, or shouldn’t, care less: live albums, live rock albums in particular, are by their nature a conceit of production.

Released in September 1979, Unleashed in the East, recorded on the Japanese leg of their Hell Bent for Leather tour, capped Judas Priest’s first long and storied decade, six months before their mainstream breakthrough British Steel. It’s a killer set, brightly produced, and enlivened some of their early material, which could tend towards studio stiffness. It was itself partly a studio effort, as singer Rob Halford had to add vocals after the fact, but anyone who loves this band or live records in general couldn’t, or shouldn’t, care less: live albums, live rock albums in particular, are by their nature a conceit of production. If they’re the only band on the infinite linear mixtape to be featured twice, and back-to-back at that, it’s because of the singularity of their two lead singers, who so influenced their respective versions of

If they’re the only band on the infinite linear mixtape to be featured twice, and back-to-back at that, it’s because of the singularity of their two lead singers, who so influenced their respective versions of  Metal is a tricky business. So is memory. I first heard “Children of the Sea” soon after it was released, I think, as a young teenager in 1980, tutored by an older sister in thrall to Rush’s Permanent Waves, Judas Priest’s Unleashed in the East, and, most of all, Black Sabbath’s Heaven and Hell. It was later that I learned of Sabbath’s late 70s identity crisis, their parting of ways with Ozzy Osbourne, and Ronnie James Dio’s efforts to help salvage a band worthy of his prowess. It couldn’t have been an easy road, and by all accounts wasn’t, BUT… the fruit of Osbourne’s dissolution, Dio’s post-Rainbow quest, and the Sabbath juggernaut’s need to produce a next record, was a pair of LPs blueprinting one way forward for metal: operatic vocal facility, pop-tinged melodies, subject matter less doom-and-gloom than dungeons-and-dragons. With, of course, guitars fully and thunderously intact. It was what Heart showed it could be with 1978’s

Metal is a tricky business. So is memory. I first heard “Children of the Sea” soon after it was released, I think, as a young teenager in 1980, tutored by an older sister in thrall to Rush’s Permanent Waves, Judas Priest’s Unleashed in the East, and, most of all, Black Sabbath’s Heaven and Hell. It was later that I learned of Sabbath’s late 70s identity crisis, their parting of ways with Ozzy Osbourne, and Ronnie James Dio’s efforts to help salvage a band worthy of his prowess. It couldn’t have been an easy road, and by all accounts wasn’t, BUT… the fruit of Osbourne’s dissolution, Dio’s post-Rainbow quest, and the Sabbath juggernaut’s need to produce a next record, was a pair of LPs blueprinting one way forward for metal: operatic vocal facility, pop-tinged melodies, subject matter less doom-and-gloom than dungeons-and-dragons. With, of course, guitars fully and thunderously intact. It was what Heart showed it could be with 1978’s  As a commercially successful American hard rock band fronted by two women in the 1970s, Heart was unique, and while it’s Patti Smith and the Runaways that have turned legendary (with merit, no doubt) for their stories, Heart’s impact on women in rock is, must be, outsized, and deserving of the same attention. While their 80s albums were marred by a soft rock sheen (but still, wildly successful), the early catalog resonates strongly: “Barracuda” with its gallop and biting reaction to a record company and music press that wanted, badly, to portray the Wilson sisters as objects of sexual intrigue; “Crazy on You”; “Magic Man”; “Straight On”; “Heartless”; “Dog and Butterfly”; “Dreamboat Annie.” For what they did and when they did it, Heart’s story is that of women in rock and roll itself, playing off and pushing against an industrial complex bent on making them something they weren’t.

As a commercially successful American hard rock band fronted by two women in the 1970s, Heart was unique, and while it’s Patti Smith and the Runaways that have turned legendary (with merit, no doubt) for their stories, Heart’s impact on women in rock is, must be, outsized, and deserving of the same attention. While their 80s albums were marred by a soft rock sheen (but still, wildly successful), the early catalog resonates strongly: “Barracuda” with its gallop and biting reaction to a record company and music press that wanted, badly, to portray the Wilson sisters as objects of sexual intrigue; “Crazy on You”; “Magic Man”; “Straight On”; “Heartless”; “Dog and Butterfly”; “Dreamboat Annie.” For what they did and when they did it, Heart’s story is that of women in rock and roll itself, playing off and pushing against an industrial complex bent on making them something they weren’t. It’s no real surprise that “Huey Newton” is not about Huey Newton but rather the rabbit holes of internet searches and the semi-free association that can result. St. Vincent’s self-titled fourth album (2014) is full of these tricky ‘scapes, it’s second single, “Digital Witness,” a frugging Beefheartian horn romp through the minefield of social media and probably the catchiest song you’ll ever hear about our accursed blessings. Annie Clark’s musical and lyrical smarts match the task of knotty commentary, so even as she obliquely declaims she does so riding a wicked beat, multiplexing fluid melodies with giant, nasty riffs shooting distorto-style from her guitar in subtle nods to

It’s no real surprise that “Huey Newton” is not about Huey Newton but rather the rabbit holes of internet searches and the semi-free association that can result. St. Vincent’s self-titled fourth album (2014) is full of these tricky ‘scapes, it’s second single, “Digital Witness,” a frugging Beefheartian horn romp through the minefield of social media and probably the catchiest song you’ll ever hear about our accursed blessings. Annie Clark’s musical and lyrical smarts match the task of knotty commentary, so even as she obliquely declaims she does so riding a wicked beat, multiplexing fluid melodies with giant, nasty riffs shooting distorto-style from her guitar in subtle nods to

You could do worse than follow the 1951 Wayne Shanklin song “Jezebel” as a guiding aesthetic for launching a recording career. A hit for Frankie Laine (1951), Edith Piaf (1951), and, remarkably, Herman’s Hermits (1966), “Jezebel” is built around a flamenco figure that adapts itself well to pop drama and, as Anna Calvi demonstrated on her first single, shows a sympathy to the reverb-y guitar dynamics and thundering tom-driven drumming favored by surf guitarists and Italian directors of Spanish-set westerns.

You could do worse than follow the 1951 Wayne Shanklin song “Jezebel” as a guiding aesthetic for launching a recording career. A hit for Frankie Laine (1951), Edith Piaf (1951), and, remarkably, Herman’s Hermits (1966), “Jezebel” is built around a flamenco figure that adapts itself well to pop drama and, as Anna Calvi demonstrated on her first single, shows a sympathy to the reverb-y guitar dynamics and thundering tom-driven drumming favored by surf guitarists and Italian directors of Spanish-set westerns. There is a little irony that Fleetwood Mac hit superstardom ten years into its existence, having jettisoned numerous guitar heroes — including the group’s founder, the inimitable and brilliant Peter Green — and did so as a West Coast soft rock band rather than the grimy British hard blues act that inspired contemporaries and was absolutely formative for Jimmy Page in his vision of

There is a little irony that Fleetwood Mac hit superstardom ten years into its existence, having jettisoned numerous guitar heroes — including the group’s founder, the inimitable and brilliant Peter Green — and did so as a West Coast soft rock band rather than the grimy British hard blues act that inspired contemporaries and was absolutely formative for Jimmy Page in his vision of