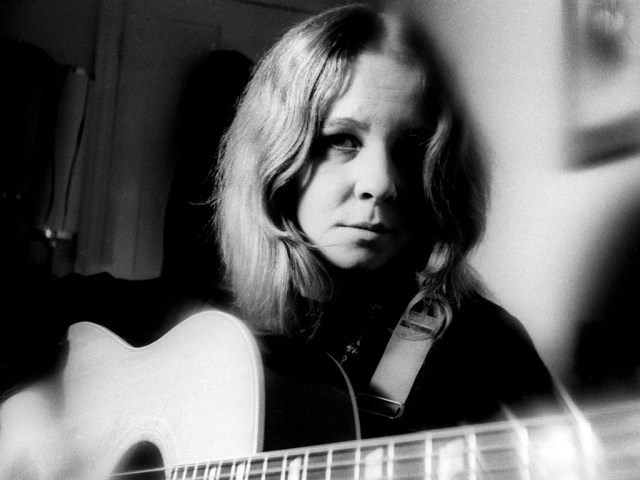

In September 1971, Sandy Denny — on the heels of an incendiary contribution to “Battle of Evermore” from Led Zeppelin‘s upcoming fourth album — released her first solo record, The North Star Grassman and the Ravens. It carried with it the strength and grace of her previous efforts, and featured many of the musicians with whom she had built her reputation, namely Richard Thompson from Fairport Convention and the entirety of Fotheringay. It was a confident beginning to a too-brief solo career, and in its quiet power illustrates why Denny’s influence on the British folk and rock scenes was so profound. Like other inhabitants of her world — thinking Thompson, Nick Drake, Lal Waterson — she was writing ahead of the curve, making deeper and contemporary connections to the wellspring of traditional folk while avoiding the easier middle earth sword epics so much of the rock world was obsessed with at the time (“Battle of Evermore” being a successful example of this).

In September 1971, Sandy Denny — on the heels of an incendiary contribution to “Battle of Evermore” from Led Zeppelin‘s upcoming fourth album — released her first solo record, The North Star Grassman and the Ravens. It carried with it the strength and grace of her previous efforts, and featured many of the musicians with whom she had built her reputation, namely Richard Thompson from Fairport Convention and the entirety of Fotheringay. It was a confident beginning to a too-brief solo career, and in its quiet power illustrates why Denny’s influence on the British folk and rock scenes was so profound. Like other inhabitants of her world — thinking Thompson, Nick Drake, Lal Waterson — she was writing ahead of the curve, making deeper and contemporary connections to the wellspring of traditional folk while avoiding the easier middle earth sword epics so much of the rock world was obsessed with at the time (“Battle of Evermore” being a successful example of this).

A sailor’s life, a lament, an existential sea chanty, “The North Star Grassman and the Ravens” has everything describing Denny’s talent: lyrical finesse, melodic beauty, the alchemical relationship of words to tune. And of course, that voice, the kind of voice that could sing the traditional “Tam Lin” with menace and authority on Fairport’s Liege and Lief (1969), and turn on a dime to deliver something as hauntingly beautiful as “The Sea,” a song of her own devise, from Fotheringay (1970).

There are three striking versions of “North Star.” The lovely studio original is shaded with classic early 70s British folk rock production (courtesy of John Wood), unfussy and earthy with a dynamic pop of bass and drums, Thompson’s restrained acoustic guitar not show-stopping but providing rhythmic chug while Ian Whiteman’s flute organ is suggestive of the hornpipe. A solo live appearance on the BBC has Denny at the piano, owning the song without a band, a confident performer on her way to becoming a national treasure. Denny recorded her last “North Star” in November 1977, just months before her death. Here, with a full electric band, the song has morphed from somber reflection to country rock grandeur. The recording was marred by technical difficulties in the guitar tracks and only released twenty years on, after Jerry Donahue (Fotheringay, Fairport) overdubbed new parts. Even with this in mind, Donahue’s playing and his history with Denny wins the day, making Gold Dust: Live at the Royalty one of the better samplers of her work.

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section.

Consider Blueshammer. Fictional, yes, short-lived, definitely (seconds at most). Daniel Clowes and Terry Zwigoff made no bones in their film Ghost World (from Clowes’ graphic novel) about white blues musicians — that is, Blueshammer — who drowned out the source of their inspiration through sheer volume, and the thoughtlessness of the fans who followed them. It’s easy pickings, sure, but there’s also some truth there, and as practitioners of the art of the blues hammer, it wasn’t the first time Led Zeppelin and their peers were skewered in pop culture (see Spinal Tap), nor would it prevent other very capable white bro’ blues artists from on the one hand shredding and posturing, and on the other (and doubly suspect I think) donning the Ray-Bans and porkpie hats and a-how-how-howing through thousands of dollars of instruments, cables, amps, etc. to legions of adoring fans. Shall we name names? No. You and they and I know who they and I and you are.

Consider Blueshammer. Fictional, yes, short-lived, definitely (seconds at most). Daniel Clowes and Terry Zwigoff made no bones in their film Ghost World (from Clowes’ graphic novel) about white blues musicians — that is, Blueshammer — who drowned out the source of their inspiration through sheer volume, and the thoughtlessness of the fans who followed them. It’s easy pickings, sure, but there’s also some truth there, and as practitioners of the art of the blues hammer, it wasn’t the first time Led Zeppelin and their peers were skewered in pop culture (see Spinal Tap), nor would it prevent other very capable white bro’ blues artists from on the one hand shredding and posturing, and on the other (and doubly suspect I think) donning the Ray-Bans and porkpie hats and a-how-how-howing through thousands of dollars of instruments, cables, amps, etc. to legions of adoring fans. Shall we name names? No. You and they and I know who they and I and you are. For every

For every  While

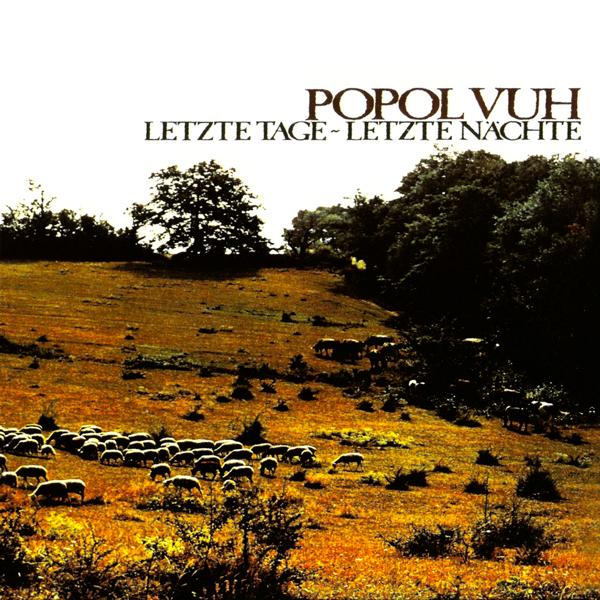

While  Beginning in 1959, John Fahey’s “Blind Joe Death” excursions for solo acoustic guitar were the first to radically reconsider traditional blues and old-time music, extending by personalizing what Harry Smith did with the Anthology of American Folk Music (1952): rather than mythologizing what at that time was a largely unknown recorded legacy, as Smith did, Fahey made it breathe life, by quoting in his riffs on the traditional all manner of contemporary music. There is not a folk or jazz or avant-garde or prog rock guitarist who doesn’t owe Fahey a debt for this, for not only breaking boundaries — with which he was hyper-literate — but making such things seem irrelevant in the music he made.

Beginning in 1959, John Fahey’s “Blind Joe Death” excursions for solo acoustic guitar were the first to radically reconsider traditional blues and old-time music, extending by personalizing what Harry Smith did with the Anthology of American Folk Music (1952): rather than mythologizing what at that time was a largely unknown recorded legacy, as Smith did, Fahey made it breathe life, by quoting in his riffs on the traditional all manner of contemporary music. There is not a folk or jazz or avant-garde or prog rock guitarist who doesn’t owe Fahey a debt for this, for not only breaking boundaries — with which he was hyper-literate — but making such things seem irrelevant in the music he made. In the last few years, David Eugene Edwards has taken

In the last few years, David Eugene Edwards has taken  A commanding presence in British punk since the later 1970s, and creating out of that — along with

A commanding presence in British punk since the later 1970s, and creating out of that — along with  It’s like they couldn’t help it, all the British bands that invented themselves in the wake of the Sex Pistols. As hard as they tried not to, they created some of the loveliest pop music one can imagine, with smarts and restraint and pretension, lots of pretension. In their willful endeavor to be a serious, art-y band in an evolving psych-goth-pop scene, Liverpool’s Echo and the Bunnymen were not the equal of Siouxsie and the Banshees or the

It’s like they couldn’t help it, all the British bands that invented themselves in the wake of the Sex Pistols. As hard as they tried not to, they created some of the loveliest pop music one can imagine, with smarts and restraint and pretension, lots of pretension. In their willful endeavor to be a serious, art-y band in an evolving psych-goth-pop scene, Liverpool’s Echo and the Bunnymen were not the equal of Siouxsie and the Banshees or the  Like Robin Pecknold of

Like Robin Pecknold of