Joe Henry always tells it like it is. What this “it” is depends on his song or object of the moment, but if artistry is about honesty then here’s a man who can be a W. Eugene Smith one minute and a Romare Bearden the next. His is an Americana in context, wrought with a realism that has to, must, consider the world beyond the borders of his song. And yet his skill at creating a complexity of life within the three- or four-minute lengths typical of his work belies this, so that his portraits are breathtaking and you are standing next to him, watching and hearing him compose a complete picture.

Joe Henry always tells it like it is. What this “it” is depends on his song or object of the moment, but if artistry is about honesty then here’s a man who can be a W. Eugene Smith one minute and a Romare Bearden the next. His is an Americana in context, wrought with a realism that has to, must, consider the world beyond the borders of his song. And yet his skill at creating a complexity of life within the three- or four-minute lengths typical of his work belies this, so that his portraits are breathtaking and you are standing next to him, watching and hearing him compose a complete picture.

1990’s Shuffletown recalls both the chamber folk-pop of Cat Stevens and the improvisational glow of Astral Weeks, T-Bone Burnett’s restrained production going live to two-track and allowing a breathing space that played against the channel-filling fashion of its time. I remember, then, marveling that an album like this could even get made anymore, much less thought of. A modern record with a backroads feel that doesn’t get lost in bucolic moods or sentiment, it is more defining in its sound and in its genre than it gets credit for. At its core — and the same could be said of Morrison’s and Stevens’ records — is an immediately recognizable voice, for Henry’s finesse with language is honored by a vocal delivery that is hip to its own thing, knows it limits and its power and its text. It’s also full of hooks, patient in its timing, finding and following melody in Shuffletown‘s deep dusks and twilight.

“The moon is losing ground, drowning in the river…”

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section above.

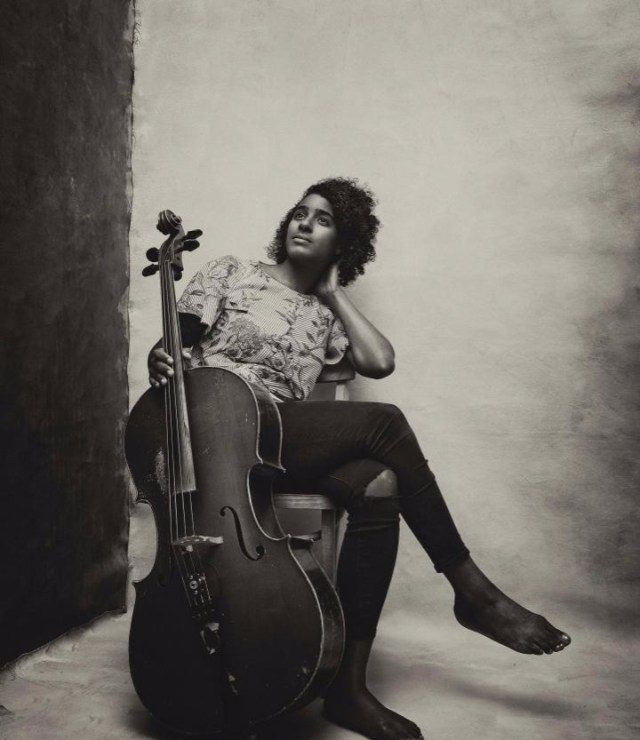

Free and blue and beautiful, those moorings Leyla McCalla holds to in her music sway and pitch like the gulf waters from Hispaniola to Lousiana, rolling through her cello and voice and coursing through her songs, lifeblood to an American music heart. In the weaving lines of the music she plays — a snaking, sliding creole so suited to, and perhaps partly a consequence of, the playing of fretless instruments — is the sound of an America taking shape as its many diasporas meet and mix and move, intersecting lines on a map that triangulate on New Orleans. Like the best Americana musicians, McCalla achieves something at once utterly contemporary but steeped in an authenticity of sound that says so much about the heart that makes the music. There’s no affected vocal, no hokum on the one hand or academic archness on the other. And there could have been, so easily. McCalla’s classically trained; she jumped from a New Jersey upbringing to a New Orleans residency; she’s an American born to Haitian rights activists in the thick of a struggle for democracy; she was an important member of the last incarnation of the much-loved Carolina Chocolate Drops. Her road was ripe for opportunity to leave the music behind in bringing a message that might not have resonated as strongly as it does. But instead she chose on her first solo record, Vari-Colored Songs (2014), to artfully adapt poetry by Langston Hughes and punctuate it with Haitian folk songs. Her second record, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, is also cloaked in a music-first approach that makes the underlying messages — because they are indeed there, as they were in her curation of Hughes’s work — so much more compelling.

Free and blue and beautiful, those moorings Leyla McCalla holds to in her music sway and pitch like the gulf waters from Hispaniola to Lousiana, rolling through her cello and voice and coursing through her songs, lifeblood to an American music heart. In the weaving lines of the music she plays — a snaking, sliding creole so suited to, and perhaps partly a consequence of, the playing of fretless instruments — is the sound of an America taking shape as its many diasporas meet and mix and move, intersecting lines on a map that triangulate on New Orleans. Like the best Americana musicians, McCalla achieves something at once utterly contemporary but steeped in an authenticity of sound that says so much about the heart that makes the music. There’s no affected vocal, no hokum on the one hand or academic archness on the other. And there could have been, so easily. McCalla’s classically trained; she jumped from a New Jersey upbringing to a New Orleans residency; she’s an American born to Haitian rights activists in the thick of a struggle for democracy; she was an important member of the last incarnation of the much-loved Carolina Chocolate Drops. Her road was ripe for opportunity to leave the music behind in bringing a message that might not have resonated as strongly as it does. But instead she chose on her first solo record, Vari-Colored Songs (2014), to artfully adapt poetry by Langston Hughes and punctuate it with Haitian folk songs. Her second record, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, is also cloaked in a music-first approach that makes the underlying messages — because they are indeed there, as they were in her curation of Hughes’s work — so much more compelling. I will never know, I mean KNOW, what a lakou is, in the same way that a Haitian will. It is a backyard, a coming together, a process, a form, a spirit. It is a community and a memory of communities stretching back through time all the way to the only successful slave revolution in recorded history and beyond. A summation and a celebration. It’s also just a freakin’ party, where all the significance of what Lakou means ends up in the bottom of a bottle of rum.

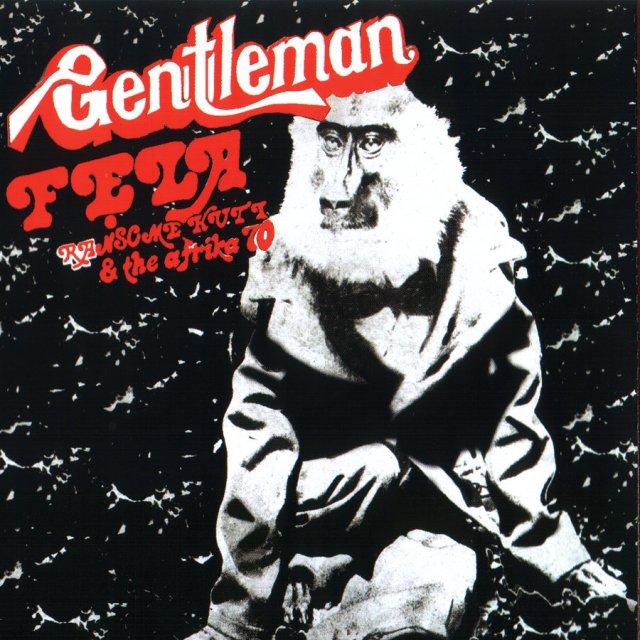

I will never know, I mean KNOW, what a lakou is, in the same way that a Haitian will. It is a backyard, a coming together, a process, a form, a spirit. It is a community and a memory of communities stretching back through time all the way to the only successful slave revolution in recorded history and beyond. A summation and a celebration. It’s also just a freakin’ party, where all the significance of what Lakou means ends up in the bottom of a bottle of rum. It can look like a conspiracy, from the outside, to know what those of us in middle America grew up with musically in the 1970s. Ensconced deeply in our Yeses and our Styxes and our REO-es and our Kansases, we often missed out on the larger view of the world, despite the delicious depths of what did come delivered over the airwaves. Case in point: Fela Kuti. The Afro beat. I suspect even if you were a jazzbo soldiering on in the post-bop wonderland delivered in the ever-widening sidelong jams of

It can look like a conspiracy, from the outside, to know what those of us in middle America grew up with musically in the 1970s. Ensconced deeply in our Yeses and our Styxes and our REO-es and our Kansases, we often missed out on the larger view of the world, despite the delicious depths of what did come delivered over the airwaves. Case in point: Fela Kuti. The Afro beat. I suspect even if you were a jazzbo soldiering on in the post-bop wonderland delivered in the ever-widening sidelong jams of

For the Clash there was no leaving politics off-record or offstage, and more than any of the mainstream punk or post-punk bands, except for maybe Gang of Four, they worked the seam in rock’s goldmine that pitted the disempowered and disenfranchised against authority, entitlement, and impunity. No mistake their hit cover of Bobby Fuller’s “I Fought the Law.” They gave punk a much-needed edge that went beyond simple nihilism, stoking it with purposeful aggression that, even as an act that in part it was, absolutely rocked. The Clash were also a band in the way the British loved their bands, from the Beatles to the

For the Clash there was no leaving politics off-record or offstage, and more than any of the mainstream punk or post-punk bands, except for maybe Gang of Four, they worked the seam in rock’s goldmine that pitted the disempowered and disenfranchised against authority, entitlement, and impunity. No mistake their hit cover of Bobby Fuller’s “I Fought the Law.” They gave punk a much-needed edge that went beyond simple nihilism, stoking it with purposeful aggression that, even as an act that in part it was, absolutely rocked. The Clash were also a band in the way the British loved their bands, from the Beatles to the  In the early 1970s in England there were a few rock bands that mattered and one that really mattered, and that was the Faces. I mean Rock band. Rock and roll. They were a supergroup, a bridge between genres, a match in a haystack. They had big hits and the best hair.

In the early 1970s in England there were a few rock bands that mattered and one that really mattered, and that was the Faces. I mean Rock band. Rock and roll. They were a supergroup, a bridge between genres, a match in a haystack. They had big hits and the best hair. Phil Lynott’s destiny — reimagining rock and roll as heavy Irish metal — meant that his band Thin Lizzy, like Motörhead and maybe AC/DC, had a claim to authenticity that punk couldn’t ignore. Lizzy’s music was lean, written with a razor, and Lynott wrung from his blackness and his Irishness every possible note of rock and roll victory in a landscape that generally counted him out. Lynott’s conversational style in song could echo

Phil Lynott’s destiny — reimagining rock and roll as heavy Irish metal — meant that his band Thin Lizzy, like Motörhead and maybe AC/DC, had a claim to authenticity that punk couldn’t ignore. Lizzy’s music was lean, written with a razor, and Lynott wrung from his blackness and his Irishness every possible note of rock and roll victory in a landscape that generally counted him out. Lynott’s conversational style in song could echo  It’s been forty-ish years since their first record but it’s not difficult to remember how important the Cars were to American music. Punk really broke with the Cars and maybe also with Devo, because until these bands hit the radio, and they did so in a big way in 1978-79, punk music and its influence was just a news story for those of us not living on America’s coasts. The Cars weren’t a punk band really at all but they brought a toughness to their pop music that defined American new wave, even as they were being played, say, between the Doobies and AC/DC on the radio (as they still are today). They represented a slew of less commercially fortunate American underground bands: Big Star, NRBQ, Flamin’ Groovies, the kind of groups who extended 60s garage rock post Beatles. That is, they saw the art in what they did. They opened ears. Ric Ocasek’s and Benjamin Orr’s lyrics were smart, un-fussy, their singing had the odd effect of creating emotional distance even while containing heartbreak, and Elliott Easton’s guitar kept the band on course — they were never not a rock band. Here on “Candy-O,” the title track of their second album, the Cars throw down a power pop gauntlet elevated by this raw live peformance. Bookended by a monster debut album and outsized 1980s success, “Candy-O” is nonetheless the band’s peak as new wave game changer.

It’s been forty-ish years since their first record but it’s not difficult to remember how important the Cars were to American music. Punk really broke with the Cars and maybe also with Devo, because until these bands hit the radio, and they did so in a big way in 1978-79, punk music and its influence was just a news story for those of us not living on America’s coasts. The Cars weren’t a punk band really at all but they brought a toughness to their pop music that defined American new wave, even as they were being played, say, between the Doobies and AC/DC on the radio (as they still are today). They represented a slew of less commercially fortunate American underground bands: Big Star, NRBQ, Flamin’ Groovies, the kind of groups who extended 60s garage rock post Beatles. That is, they saw the art in what they did. They opened ears. Ric Ocasek’s and Benjamin Orr’s lyrics were smart, un-fussy, their singing had the odd effect of creating emotional distance even while containing heartbreak, and Elliott Easton’s guitar kept the band on course — they were never not a rock band. Here on “Candy-O,” the title track of their second album, the Cars throw down a power pop gauntlet elevated by this raw live peformance. Bookended by a monster debut album and outsized 1980s success, “Candy-O” is nonetheless the band’s peak as new wave game changer.