*above image by R. Crumb.

Bob Dylan is the rare artist who, at 75, retains the power, energy, and restlessness that distinguished his early work. As both a recording and performing artist, his electricity is unabated, and he continues to make vibrant contributions to the post-folk culture he virtually created. That he has achieved this is astounding; for those of us who have followed his career and know something of its roots and evolution, it is not surprising. He constantly recasts his song catalogue, the depth of which by 1965 (let alone 2016) was unrivaled in the rock/folk/singer-songwriter genre he invented, to match his current sound, and commands a fluidity of vision in his writing that sees beyond the trees and perhaps the forest as well. Witness “High Water,” a tribute to Charley Patton (whose “High Water Everywhere” is a stone cold delta blues barking, howling, classic), from 2001’s Love and Theft. This is a blues about love and the water that rises, that has picked up some oldtime, some drone, shaking and breaking and name-checking muscle cars and evolutionary philosophers. The thing is that it works because when Dylan sings “the cuckoo is a pretty bird” that’s a kind of referenced code that he’s hollering back to Patton. He’s writing a blank check to freely associate (find and listen to a version of “The Cuckoo” and you’ll get what I mean), to make the rhyme work and throw meaning to the wind and to the listener. Harder than it sounds because it’s about the sound, what music is, what makes its power inexplicable. To make that warble on the 5th day of July, and trace your absurd and beautiful melody: it takes courage and a resolution that comes at a price only Dylan, and maybe Patton, knows.

Bob Dylan is the rare artist who, at 75, retains the power, energy, and restlessness that distinguished his early work. As both a recording and performing artist, his electricity is unabated, and he continues to make vibrant contributions to the post-folk culture he virtually created. That he has achieved this is astounding; for those of us who have followed his career and know something of its roots and evolution, it is not surprising. He constantly recasts his song catalogue, the depth of which by 1965 (let alone 2016) was unrivaled in the rock/folk/singer-songwriter genre he invented, to match his current sound, and commands a fluidity of vision in his writing that sees beyond the trees and perhaps the forest as well. Witness “High Water,” a tribute to Charley Patton (whose “High Water Everywhere” is a stone cold delta blues barking, howling, classic), from 2001’s Love and Theft. This is a blues about love and the water that rises, that has picked up some oldtime, some drone, shaking and breaking and name-checking muscle cars and evolutionary philosophers. The thing is that it works because when Dylan sings “the cuckoo is a pretty bird” that’s a kind of referenced code that he’s hollering back to Patton. He’s writing a blank check to freely associate (find and listen to a version of “The Cuckoo” and you’ll get what I mean), to make the rhyme work and throw meaning to the wind and to the listener. Harder than it sounds because it’s about the sound, what music is, what makes its power inexplicable. To make that warble on the 5th day of July, and trace your absurd and beautiful melody: it takes courage and a resolution that comes at a price only Dylan, and maybe Patton, knows.

Years before the hybrid of classic rock and distorted garage psychedelia and punk became the legendary Grunge that vanquished the Hair Metal Dragon in the early 1990s, Screaming Trees and Thin White Rope plied their trade in relative obscurity and penury. Even as “punk broke” in America and they were afforded greater opportunity for exposure, as groups they had already cycled through lineup changes and masterwork albums, and the timing for broad success never really synced. Yet you can sight through the lens of their recorded legacy an understanding of what Grunge in America was, where it came from, what it meant, how it drew upon American roots music, acknowledging what Greil Marcus called the “old, weird America,” of everything from 13th Floor Elevators and Neil Young to the folk revival of the 1960s to the hillbilly/race records of the 1920s and 1930s. The references aren’t always apparent, but they’re embedded in the dust devils Thin White Rope appeared through and the rain-soaked northwestern pines the Screaming Trees turned dayglo.

Years before the hybrid of classic rock and distorted garage psychedelia and punk became the legendary Grunge that vanquished the Hair Metal Dragon in the early 1990s, Screaming Trees and Thin White Rope plied their trade in relative obscurity and penury. Even as “punk broke” in America and they were afforded greater opportunity for exposure, as groups they had already cycled through lineup changes and masterwork albums, and the timing for broad success never really synced. Yet you can sight through the lens of their recorded legacy an understanding of what Grunge in America was, where it came from, what it meant, how it drew upon American roots music, acknowledging what Greil Marcus called the “old, weird America,” of everything from 13th Floor Elevators and Neil Young to the folk revival of the 1960s to the hillbilly/race records of the 1920s and 1930s. The references aren’t always apparent, but they’re embedded in the dust devils Thin White Rope appeared through and the rain-soaked northwestern pines the Screaming Trees turned dayglo.

By the time Screaming Trees came to record Sweet Oblivion (1992), they were already five albums deep into a psych rock career stamped by Gary Lee Conner’s guitar raveups and Mark Lanegan’s authoritative, rumbling wail. On their sixth album, though, there was a changeup: the band, with new drummer Barrett Martin, followed the Americana-nuanced maturity evidenced on Lanegan’s first solo album, 1990’s The Winding Sheet (a record that had a profound influence on Seattle’s rock scene and on Nirvana particularly — Kurt Cobain was a contributor on that record and Dave Grohl has commented that it had a big impact on their approach to Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged performance). On Sweet Oblivion, the band set their controls to the heart of the West, making the followup to 1991’s excellent Uncle Anesthesia a harder yet subtler, less ornate affair. Gone were the psychedelic trappings, in their place a clutch of straight-up riff rockers and ballads, going deep by going personal rather than into the purple, foggy haze. Beginning to end a great record that to this day sounds distinct and powerful listened to alongside Nevermind or Ten or Temple of the Dog or Superunknown or Dirt, Sweet Oblivion just never took off, and to my mind the greatest of Seattle’s bands never recovered. “Winter Song” begins and ends with the line “Jesus knocking on my door,” and it’s as fitting an epitaph for a band that shouldabeen that I can think of.

Like Sweet Oblivion, Thin White Rope’s fourth album, Sack Full of Silver (1990), is an American music classic. Ported through a Television-worthy twin-guitar attack, its power is in the finesse of its six-string thunder and Guy Kyser’s gruff, horror show bark. It is a record that manages to contain both a cover of Can’s “Yoo Doo Right” AND a 7-11 parking lot rewrite of “Amazing Grace” and makes them work as if they absolutely belong on the same album. Along with guitarist Roger Kunkel, Kyser’s vision of 1980s western America on Sack Full of Silver — highways and truck stops and stoned mirage images — is fully realized, but feels like it could have as easily been recorded, had the technology been possible, in the 1850s, with a mix of frontier terror and mundane everyday life. Profound, pounding, and heavy, Sack Full of Silver is the distillation of all that Thin White Rope brought to rock. As opaque as any of their songs, but endlessly interesting for it, “Whirling Dervish” is ostensibly about detritus caught in a duststorm, and may as a consequence be ultimately descriptive of all of us.

For years, LA’s Red Temple Spirits were a tease, a psych rock ghost that once got a short write-up in Rolling Stone, which gave an address to write to if you wanted the album, an address for an obscure label that never wrote back. It was the pre-internet treasure map to sacred recordings process that was our siren’s call. Guesswork, album reviews, dudes in record stores who’d gone to see Hendrix and never really come back. From the description I read, this band was for me. But for about five years, every record store I walked into got the question: “Red Temple Spirits?” and I would receive a shake of the head back. Along with Television Personalities, in the late 80s and early 90s they were my grail, a band whose records couldn’t seem to be found for love or money, as if they wanted it that way, ached to be left alone. Around 1993 I finally and gratefully scored a cassette of their 1989 album If tomorrow I were leaving for Lhasa I wouldn’t stay a minute more… (possibly from Austin’s Waterloo records, who had hooked me up with Television Personalities a couple years earlier too) and discovered the small window of hype Rolling Stone gave them was deserved. A rockier, psychier version of the Cure, Red Temple Spirits was everything I had wanted the Cult to become after their album Love. Possessing in William Faircloth a vocalist who channeled Syd Barrett and Robert Smith through songs that showed a clear sense of identity and sound, the two albums the band released were post-punk goth psychedelic sendups that captured one strain of late ’80s/early ’90s indie rock across the country. Every scene had their version of this band, but being on the west coast gave the Red Temple Spirits greater context as part of that region’s psychedelic revival — I can easily place them with Opal and Shiva Burlesque and Rain Parade, Camper Van Beethoven and Thin White Rope and Screaming Trees. If in their day their music was nearly impossible to find, it is now widely available, and can have the legacy it’s long deserved. “In the Wild Hills” is a favorite, a thunderous, trippy, tribal fantasy that works because it’s all in. The spirits never sleep.

For years, LA’s Red Temple Spirits were a tease, a psych rock ghost that once got a short write-up in Rolling Stone, which gave an address to write to if you wanted the album, an address for an obscure label that never wrote back. It was the pre-internet treasure map to sacred recordings process that was our siren’s call. Guesswork, album reviews, dudes in record stores who’d gone to see Hendrix and never really come back. From the description I read, this band was for me. But for about five years, every record store I walked into got the question: “Red Temple Spirits?” and I would receive a shake of the head back. Along with Television Personalities, in the late 80s and early 90s they were my grail, a band whose records couldn’t seem to be found for love or money, as if they wanted it that way, ached to be left alone. Around 1993 I finally and gratefully scored a cassette of their 1989 album If tomorrow I were leaving for Lhasa I wouldn’t stay a minute more… (possibly from Austin’s Waterloo records, who had hooked me up with Television Personalities a couple years earlier too) and discovered the small window of hype Rolling Stone gave them was deserved. A rockier, psychier version of the Cure, Red Temple Spirits was everything I had wanted the Cult to become after their album Love. Possessing in William Faircloth a vocalist who channeled Syd Barrett and Robert Smith through songs that showed a clear sense of identity and sound, the two albums the band released were post-punk goth psychedelic sendups that captured one strain of late ’80s/early ’90s indie rock across the country. Every scene had their version of this band, but being on the west coast gave the Red Temple Spirits greater context as part of that region’s psychedelic revival — I can easily place them with Opal and Shiva Burlesque and Rain Parade, Camper Van Beethoven and Thin White Rope and Screaming Trees. If in their day their music was nearly impossible to find, it is now widely available, and can have the legacy it’s long deserved. “In the Wild Hills” is a favorite, a thunderous, trippy, tribal fantasy that works because it’s all in. The spirits never sleep.

The Cure’s Disintegration is a lush, beautiful masterpiece. When it was released in 1989, the band was cresting a wave of popularity, and rare was the college dorm room in America that didn’t have a copy of their singles comp, Staring at the Sea (1986), sitting next to the deck, while Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me (1987) was radio ready. Robert Smith had become an unlikely hero, a post-punk goth who had paid his dues and, with a colossal songwriting talent, was reaping the rewards of someone who virtually created his own genre. Nobody else sounded like the Cure. Neither psychedelic nor prog nor punk, but fearless in their approach, comfortable in their painted skin. On Disintegration the band slows the tempos, backgrounding Smith’s economical lyrics with huge keyboard/guitar drift pieces that seem to exist in the gloaming. A perpetually wilting flower, the first-person character in Smith’s work has had a long shelf life, and would rot if it weren’t for Smith’s genius with song and his ability to effortlessly write pop hits at will. Entreat is from the tour supporting the album, recorded at Wembley in ’89, and consists of the all the songs on Disintegration in the same running order. It had a very limited release originally, but pieces of it emerged here and there on CD singles taken from Disintegration (I first heard parts of it on the Pictures of You EP), and was eventually, finally bundled with Disintegration on the 2010 re-release. Entreat was a bold move, a full performance of a newly-released record, and demonstrates just how confident Smith and his band were in the new songs.

The Cure’s Disintegration is a lush, beautiful masterpiece. When it was released in 1989, the band was cresting a wave of popularity, and rare was the college dorm room in America that didn’t have a copy of their singles comp, Staring at the Sea (1986), sitting next to the deck, while Kiss Me Kiss Me Kiss Me (1987) was radio ready. Robert Smith had become an unlikely hero, a post-punk goth who had paid his dues and, with a colossal songwriting talent, was reaping the rewards of someone who virtually created his own genre. Nobody else sounded like the Cure. Neither psychedelic nor prog nor punk, but fearless in their approach, comfortable in their painted skin. On Disintegration the band slows the tempos, backgrounding Smith’s economical lyrics with huge keyboard/guitar drift pieces that seem to exist in the gloaming. A perpetually wilting flower, the first-person character in Smith’s work has had a long shelf life, and would rot if it weren’t for Smith’s genius with song and his ability to effortlessly write pop hits at will. Entreat is from the tour supporting the album, recorded at Wembley in ’89, and consists of the all the songs on Disintegration in the same running order. It had a very limited release originally, but pieces of it emerged here and there on CD singles taken from Disintegration (I first heard parts of it on the Pictures of You EP), and was eventually, finally bundled with Disintegration on the 2010 re-release. Entreat was a bold move, a full performance of a newly-released record, and demonstrates just how confident Smith and his band were in the new songs.

Finding abandon in structure is what rock is about, but it’s rarely approached with such intentional power as on the live sets that Robert Fripp and David Sylvian played in Japan in 1993, which make up the album Damage and the film presented here, Road to Graceland: Live in Japan 1993. It’s not surprising that one of the great live albums in rock would come from a duo whose very distinct songwriting and voices meshed with such ease, but the precious vein they mined yielded such a small set of work and such little attention — after all, art rock/pop in the early 90s was in a far different place in the popular consciousness than it had been a decade earlier — that the record is nearly invisible today even if you’re fairly well-acquainted with the careers of both men. This is neither In the Court of the Crimson King (or Discipline) or Gentleman Take Polaroids (or Rain Tree Crow), but a striving towards something that summed higher, capturing two artists with deep histories and still in their prime. Fripp’s work here, as always, is masterful; a guitarist whose technical ability is matched by a uniquely creative sound and spirit and generosity, he creates space for Sylvian’s profoundly expressive voice and writing. Sylvian, in turn, doesn’t fill the frame either, yielding his significant presence when necessary to the outstanding band he’s playing with. This is my favorite pairing of Fripp with a vocalist, because as much as I like the work he did in King Crimson with Adrian Belew in the 80s and John Wetton in the 70s, he and Sylvian have a chemistry that gets to the center of their strengths, and, appropriately — given Fripp’s brief but incendiary participation in the Berlin Trilogy — summons the work of Eno and Bowie. With Fripp familiars Trey Gunn and Pat Mastelotto, and Michael Brook on additional guitar, the band kills, in a performance as intimate and deep as the emotions and moods that Sylvian and Fripp stir.

Finding abandon in structure is what rock is about, but it’s rarely approached with such intentional power as on the live sets that Robert Fripp and David Sylvian played in Japan in 1993, which make up the album Damage and the film presented here, Road to Graceland: Live in Japan 1993. It’s not surprising that one of the great live albums in rock would come from a duo whose very distinct songwriting and voices meshed with such ease, but the precious vein they mined yielded such a small set of work and such little attention — after all, art rock/pop in the early 90s was in a far different place in the popular consciousness than it had been a decade earlier — that the record is nearly invisible today even if you’re fairly well-acquainted with the careers of both men. This is neither In the Court of the Crimson King (or Discipline) or Gentleman Take Polaroids (or Rain Tree Crow), but a striving towards something that summed higher, capturing two artists with deep histories and still in their prime. Fripp’s work here, as always, is masterful; a guitarist whose technical ability is matched by a uniquely creative sound and spirit and generosity, he creates space for Sylvian’s profoundly expressive voice and writing. Sylvian, in turn, doesn’t fill the frame either, yielding his significant presence when necessary to the outstanding band he’s playing with. This is my favorite pairing of Fripp with a vocalist, because as much as I like the work he did in King Crimson with Adrian Belew in the 80s and John Wetton in the 70s, he and Sylvian have a chemistry that gets to the center of their strengths, and, appropriately — given Fripp’s brief but incendiary participation in the Berlin Trilogy — summons the work of Eno and Bowie. With Fripp familiars Trey Gunn and Pat Mastelotto, and Michael Brook on additional guitar, the band kills, in a performance as intimate and deep as the emotions and moods that Sylvian and Fripp stir.

Forty years on it seems like it must have been inevitable, obvious even, the crossing paths of Iggy Pop and David Bowie and Brian Eno and Robert Fripp, in service to Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy. In Act Two of their collective careers, they became in the late 1970s the center of a wheel spoking to progressive rock, art rock, post punk, and new wave, the albums coming out of Bowie’s residency in Berlin among the richest, most genre-defying rock records created, documents of a grasp catching up with its reach. “Warszawa” is from 1977’s Low, the second Berlin collaboration (after Pop’s The Idiot, for the trilogy is really a quintet, taking into account the records Bowie produced for Iggy during this period) and a document of Bowie’s dissolving spirits. Here is where he throws the hammer at the mirror, where all his past characters like Ziggy and the Thin White Duke are shown the door. The sound is fresh, with Eno, coming off his work with Cluster, applying broadly-stroked synth washes straight from the school of Moebius and Roedelius, encouraging Bowie to approach the music with deliberate freedom. The result, like on the song “Sound and Vision,” is raw and buoyant. It can also be wild and studied, as on the constraint-driven “Warszawa,” an exercise in composition employing Eno’s planned accidents and oblique strategies. In it, as on much of the album, you can hear an origin story of bands like U2 and Echo and the Bunnymen and Joy Division/New Order, and a second-wind promise Bowie himself would continue to fulfill, off and on, for the rest of his life.

Forty years on it seems like it must have been inevitable, obvious even, the crossing paths of Iggy Pop and David Bowie and Brian Eno and Robert Fripp, in service to Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy. In Act Two of their collective careers, they became in the late 1970s the center of a wheel spoking to progressive rock, art rock, post punk, and new wave, the albums coming out of Bowie’s residency in Berlin among the richest, most genre-defying rock records created, documents of a grasp catching up with its reach. “Warszawa” is from 1977’s Low, the second Berlin collaboration (after Pop’s The Idiot, for the trilogy is really a quintet, taking into account the records Bowie produced for Iggy during this period) and a document of Bowie’s dissolving spirits. Here is where he throws the hammer at the mirror, where all his past characters like Ziggy and the Thin White Duke are shown the door. The sound is fresh, with Eno, coming off his work with Cluster, applying broadly-stroked synth washes straight from the school of Moebius and Roedelius, encouraging Bowie to approach the music with deliberate freedom. The result, like on the song “Sound and Vision,” is raw and buoyant. It can also be wild and studied, as on the constraint-driven “Warszawa,” an exercise in composition employing Eno’s planned accidents and oblique strategies. In it, as on much of the album, you can hear an origin story of bands like U2 and Echo and the Bunnymen and Joy Division/New Order, and a second-wind promise Bowie himself would continue to fulfill, off and on, for the rest of his life.

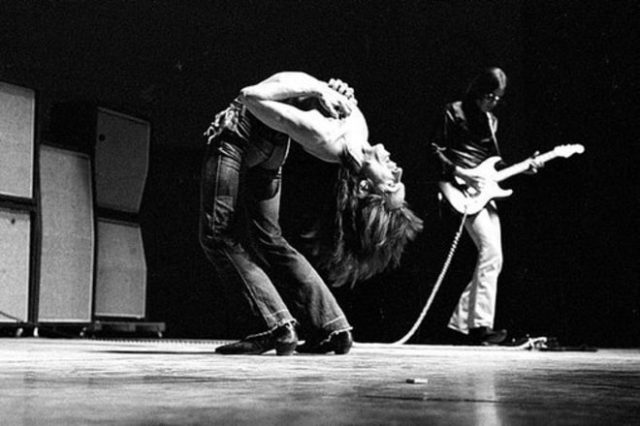

Three months after Miles Davis unleashed Bitches Brew on the rock and jazz worlds, the Stooges second record, Fun House, appeared. Like Davis, like a lot of music in 1970, the band was looking for the elemental, pushed by psychedelics to the fringes of structure, open minds creating extremes of focus. For the Stooges that meant following the train to the auto plants of Detroit, putting into music the sisyphian rhythm of the line, in the same way that Maurice Ravel cited in Bolero his memories of the factory his father worked in. The merciless repetition, the stamping power of machinery. Already one album into creating a trinity of punk rock templates, the Stooges on Fun House sound at once heavier, funkier, freer than they did on Stooges. Bringing in fellow Michiganer Steve Mackay on saxophone, whose presence created both space and chaos, the band occupied a far more complex and dangerous place than probably anyone around them truly expected, finding at their crossroads a vévé made of free jazz and Louie Louie, summoning the era’s riots and Kent States and Vietnams, holding up the same mirror that Hendrix traveled through in “Machine Gun” or Funkadelic gazed into on “Wars of Armageddon.” But at the end of it there’s no message of peace and love or some kind of lesson learned. It’s really a blank stare, a do-what-you-will-with-this, a Punk manifesto. It’s no wonder, although still kind of remarkable, that Miles Davis thought the group was good, or at least that their cocaine was excellent. The song “1970” begins the album’s second, disintegrating half, an answer to “1969” from Stooges, with Iggy’s proclamation “I feel alright!” feeling anything but. It’s the dark stuff, completely and totally honest, because Iggy probably always did feel alright when things went to the edge. The Stooges cut deep, to the bone, burning towards the true dark star of rock and roll.

Three months after Miles Davis unleashed Bitches Brew on the rock and jazz worlds, the Stooges second record, Fun House, appeared. Like Davis, like a lot of music in 1970, the band was looking for the elemental, pushed by psychedelics to the fringes of structure, open minds creating extremes of focus. For the Stooges that meant following the train to the auto plants of Detroit, putting into music the sisyphian rhythm of the line, in the same way that Maurice Ravel cited in Bolero his memories of the factory his father worked in. The merciless repetition, the stamping power of machinery. Already one album into creating a trinity of punk rock templates, the Stooges on Fun House sound at once heavier, funkier, freer than they did on Stooges. Bringing in fellow Michiganer Steve Mackay on saxophone, whose presence created both space and chaos, the band occupied a far more complex and dangerous place than probably anyone around them truly expected, finding at their crossroads a vévé made of free jazz and Louie Louie, summoning the era’s riots and Kent States and Vietnams, holding up the same mirror that Hendrix traveled through in “Machine Gun” or Funkadelic gazed into on “Wars of Armageddon.” But at the end of it there’s no message of peace and love or some kind of lesson learned. It’s really a blank stare, a do-what-you-will-with-this, a Punk manifesto. It’s no wonder, although still kind of remarkable, that Miles Davis thought the group was good, or at least that their cocaine was excellent. The song “1970” begins the album’s second, disintegrating half, an answer to “1969” from Stooges, with Iggy’s proclamation “I feel alright!” feeling anything but. It’s the dark stuff, completely and totally honest, because Iggy probably always did feel alright when things went to the edge. The Stooges cut deep, to the bone, burning towards the true dark star of rock and roll.

It’s unavoidable. It is impossible to speak of modern music, regardless of genre, and not take note of the critical importance of Miles Davis. Call him what you will or what he called himself — a genius of composition, a dazzling trumpeter/performer and band leader/manipulator, an agent provocateur, a counter-racist, coke fiend, pimp, misogynist — Miles Davis was to musical art what Pablo Picasso was to visual art in the 20th century. It’s so true it’s not even up for debate, and there’s about a kazillion hours of recorded, generous, lovely, dark, funky, bopping proof. By natural extension Davis was the incarnation of what Ravel’s Bolero was all about — schooled freedom, the connection of craft and wild will, the fearlessness to create shit one second and be the divine and golden voice of the Spirit the next. By the time Miles Davis released Bitches Brew in 1970, he’d been creating killer jazz for over 20 years, had broken from the pack a decade earlier with the “modal” music of Kind of Blue (1959), and had crafted blueprints for psychedelic and progressive rock in the music he created between Sketches of Spain (1960) and In A Silent Way (1969). He was a complete musician who, difficult as he was, found sympathetic producers, promoters, and partners who fed and nurtured his bright flame. As we find him on “Spanish Key,” Davis’s work is still melodic, free and open, but deconstruction is increasingly what he’s about — he’s using the studio as an instrument, playing less, knitting together jams, finding the overlap of blues and jazz and funk, Waters and Ellington and Brown. He was 44 years old, electric with creativity and swaggering with confidence, inspiring and inspired by rock’s reach towards jazz through Hendrix and Santana the Family Stone. But for all the trappings of the rock band that he took with him to the stage, he never yielded, in the sheer sonic amplified power, any of jazz’s mysteries and his own mastery. He delighted in pointing out that he could go to rock, but rock could not come to him. It’s certainly true, to the extent that Miles Davis had a transcending vision and the untameable talent to back it up. There is not another record in jazz or rock like Bitches Brew, and there never again will be. It is a difficult, beautiful ride.

It’s unavoidable. It is impossible to speak of modern music, regardless of genre, and not take note of the critical importance of Miles Davis. Call him what you will or what he called himself — a genius of composition, a dazzling trumpeter/performer and band leader/manipulator, an agent provocateur, a counter-racist, coke fiend, pimp, misogynist — Miles Davis was to musical art what Pablo Picasso was to visual art in the 20th century. It’s so true it’s not even up for debate, and there’s about a kazillion hours of recorded, generous, lovely, dark, funky, bopping proof. By natural extension Davis was the incarnation of what Ravel’s Bolero was all about — schooled freedom, the connection of craft and wild will, the fearlessness to create shit one second and be the divine and golden voice of the Spirit the next. By the time Miles Davis released Bitches Brew in 1970, he’d been creating killer jazz for over 20 years, had broken from the pack a decade earlier with the “modal” music of Kind of Blue (1959), and had crafted blueprints for psychedelic and progressive rock in the music he created between Sketches of Spain (1960) and In A Silent Way (1969). He was a complete musician who, difficult as he was, found sympathetic producers, promoters, and partners who fed and nurtured his bright flame. As we find him on “Spanish Key,” Davis’s work is still melodic, free and open, but deconstruction is increasingly what he’s about — he’s using the studio as an instrument, playing less, knitting together jams, finding the overlap of blues and jazz and funk, Waters and Ellington and Brown. He was 44 years old, electric with creativity and swaggering with confidence, inspiring and inspired by rock’s reach towards jazz through Hendrix and Santana the Family Stone. But for all the trappings of the rock band that he took with him to the stage, he never yielded, in the sheer sonic amplified power, any of jazz’s mysteries and his own mastery. He delighted in pointing out that he could go to rock, but rock could not come to him. It’s certainly true, to the extent that Miles Davis had a transcending vision and the untameable talent to back it up. There is not another record in jazz or rock like Bitches Brew, and there never again will be. It is a difficult, beautiful ride.

Maurice Ravel’s Boléro has a long, complex relationship with rock and roll, sometimes quoted explicitly (Jeff Beck’s “Beck’s Bolero”) other times through suggestion (Rush’s “Jacob’s Ladder”). In its thematic and rhythmic repetition and building orchestration there is a tension and release, an erotic energy inseparable from rock’s spark. This has often been perceived as a weakness of the work, even signaling cultural dissolution, to its detractors.* Ravel himself had misgivings about the piece, and almost immediately following its first performance equivocated on what exactly he had created.

Maurice Ravel’s Boléro has a long, complex relationship with rock and roll, sometimes quoted explicitly (Jeff Beck’s “Beck’s Bolero”) other times through suggestion (Rush’s “Jacob’s Ladder”). In its thematic and rhythmic repetition and building orchestration there is a tension and release, an erotic energy inseparable from rock’s spark. This has often been perceived as a weakness of the work, even signaling cultural dissolution, to its detractors.* Ravel himself had misgivings about the piece, and almost immediately following its first performance equivocated on what exactly he had created.

I am particularly desirous that there should be no misunderstanding about this work. It constitutes an experiment in a very special and limited direction, and should not be suspected of aiming at achieving anything different from, or anything more than, it actually does achieve… The themes are altogether impersonal – folk-tunes of the usual Spanish-Arabian kind, and (whatever may have been said to the contrary) the orchestral writing is simple and straightforward throughout, without the slightest attempt at virtuosity… It is perhaps because of these peculiarities that no single composer likes the Boléro – and from their point of view they are quite right. I have carried out exactly what I intended, and it is for the listeners to take it or leave it. — Maurice Ravel, London Daily Telegraph, July 1931.

This is a primordial punk/art statement, the “take it or leave it” a rejection of the academy, rock and roll’s essence, defying established thought but not without some churning within. It takes some mastery of a form to be able to do this, and so the statement is no easy out for the composer. His qualifications are not rationalizations or apologies, but a struggle with what he’s wrought. Boléro is a masterpiece, and like many orchestral works it is a shapeshifter. It tends towards 10 minutes in length or 19 — although Ravel preferred it to be in the 15- to 16-minute range. It is an arabesque, a sketch of Spain, a jazz age jewel, a childhood memory, a factory rhythm, an experiment, a riff monster, an impulse, an excercise, a piece of wizardly power. It is very occasionally, as it was originally, the score to a ballet. It is in its essence enigmatic. Even the better recorded version, and there are many out there, is a topic of fierce debate among aficionados. Many prefer Charles Munch’s RCA Living Stereo version from the 1950s, but at 13 minutes it quick-times the proceedings, undoubtedly for the consideration of the LP and perhaps influenced by the Toscanini performance that popularized the work in America, at a tempo that set the composer and conductor at odds. If it’s true, the story is great:

Ravel: That’s not my tempo.

Toscanini: When I play it at your tempo, it is not effective.

Ravel: Then do not play it.

Many longer versions are out there, however, and it’s probably hard to find one, fast or slow, that isn’t at least a little great, as it is apparently quite difficult not to knock this one out of the park if the conductor can keep the pace steady. For the sake of authenticity here is presented the 1930 version conducted by Ravel himself, or perhaps by Albert Wolff with Ravel present (this too is a topic of some debate) and approving. The provenance is sketchy, lost in the murk and mire of Ravel’s looming madness, the carelessness of record companies, and the vagaries of YouTube; however, this performance is most likely from 1930 with the Orchestre De L’Association Des Concerts Lamoureux.

* Allan Bloom famously called it the only classical piece of music young people liked, as puzzling “proof” — for who knows what that survey must have looked like — that everything was going to hell in the 1980s.

** Above painting of dancer/actress Ida Rubinstein, who commissioned Ravel to write the piece, by Valentin Serov (Wikipedia).