While John Fahey was working on the set of songs that included “Sunny Side of the Ocean,” for The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death (1965), he was completing his master’s thesis in folklore at the University of California at Berkeley, the first biography and analysis of the work of blues guitarist/singer Charley Patton. It was published in paperback form in 1970 and is now considered a classic of blues literature. (Like most early Fahey endeavors, original printings go for exorbitant sums. However, indulge yourself here for free.) Fahey’s obsession with Patton is clear but also realistic, and contains in it the reach and grasp of a true scholar. One gets the impression he probably could have rattled this off in his sleep, despite the occasional dry stiffness no doubt desired by his thesis committee. Fahey’s point: blues and folk scholarship was missing out big on players like Patton, who for years had been written off as being past the cut-off point of interest of circa 1928, i.e., more influenced by records than oral tradition and thus not worth bothering over. The racism banked deep in this position aside, Fahey argues successfully that the atmosphere of non-direction in the recording studio for blues artists of Patton’s era (1929-1934) in particular — a result of A&R men having no idea what black communities wanted in the “race records” they were promoting to those same communities — gave players like Patton freedom to perform more naturally than they might otherwise, and produced work that provided a window into African American existence in the Mississippi Delta in the first half of the 20th century.

While John Fahey was working on the set of songs that included “Sunny Side of the Ocean,” for The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death (1965), he was completing his master’s thesis in folklore at the University of California at Berkeley, the first biography and analysis of the work of blues guitarist/singer Charley Patton. It was published in paperback form in 1970 and is now considered a classic of blues literature. (Like most early Fahey endeavors, original printings go for exorbitant sums. However, indulge yourself here for free.) Fahey’s obsession with Patton is clear but also realistic, and contains in it the reach and grasp of a true scholar. One gets the impression he probably could have rattled this off in his sleep, despite the occasional dry stiffness no doubt desired by his thesis committee. Fahey’s point: blues and folk scholarship was missing out big on players like Patton, who for years had been written off as being past the cut-off point of interest of circa 1928, i.e., more influenced by records than oral tradition and thus not worth bothering over. The racism banked deep in this position aside, Fahey argues successfully that the atmosphere of non-direction in the recording studio for blues artists of Patton’s era (1929-1934) in particular — a result of A&R men having no idea what black communities wanted in the “race records” they were promoting to those same communities — gave players like Patton freedom to perform more naturally than they might otherwise, and produced work that provided a window into African American existence in the Mississippi Delta in the first half of the 20th century.

Fahey’s efforts notwithstanding, Patton remains a dazzling mystery, dead and mostly forgotten for over thirty years before Fahey’s scholarship and the debts acknowledged by artists like Bob Dylan. Far wilder in lifestyle and presentation than that other King of the Delta Blues, Robert Johnson (himself no stranger to the on-the-edge, rough life of an itinerant Delta musician) Patton’s repertoire was also more diverse, and his showmanship as much a part of his legend as his musicianship to the people who knew him and had seen him perform (to the extent that Son House expressed surprise to Fahey on hearing a Patton record Fahey played back for him, not recalling his friend’s potent guitar prowess but instead Patton’s “clowning”). While Patton’s legacy never attained the rock’n’roll sanctification accorded Johnson’s work — there’s no equivalent for Patton to Cream’s cover of Johnson’s “Crossroads” or the Stones’ “Stop Breaking Down” — his work constitutes in its rawness an essential rock document, the direct antecedent to the entire career of Howlin’ Wolf (who Patton mentored), and thus by association Captain Beefheart and Tom Waits. So if Robert Johnson is closely associated with classic blues rock as exemplified by Cream and the jam bands that followed, Patton can to some degree be claimed by artists who inhabit rock’s lunatic fringe. This isn’t, of course, an all-or-nothing proposition, but just one possible, shifting observation. Patton was a punk.

Continue reading “soundstreamsunday #90: “A Spoonful Blues” by Charley Patton”

Joe Henry always tells it like it is. What this “it” is depends on his song or object of the moment, but if artistry is about honesty then here’s a man who can be a W. Eugene Smith one minute and a Romare Bearden the next. His is an Americana in context, wrought with a realism that has to, must, consider the world beyond the borders of his song. And yet his skill at creating a complexity of life within the three- or four-minute lengths typical of his work belies this, so that his portraits are breathtaking and you are standing next to him, watching and hearing him compose a complete picture.

Joe Henry always tells it like it is. What this “it” is depends on his song or object of the moment, but if artistry is about honesty then here’s a man who can be a W. Eugene Smith one minute and a Romare Bearden the next. His is an Americana in context, wrought with a realism that has to, must, consider the world beyond the borders of his song. And yet his skill at creating a complexity of life within the three- or four-minute lengths typical of his work belies this, so that his portraits are breathtaking and you are standing next to him, watching and hearing him compose a complete picture. I will never know, I mean KNOW, what a lakou is, in the same way that a Haitian will. It is a backyard, a coming together, a process, a form, a spirit. It is a community and a memory of communities stretching back through time all the way to the only successful slave revolution in recorded history and beyond. A summation and a celebration. It’s also just a freakin’ party, where all the significance of what Lakou means ends up in the bottom of a bottle of rum.

I will never know, I mean KNOW, what a lakou is, in the same way that a Haitian will. It is a backyard, a coming together, a process, a form, a spirit. It is a community and a memory of communities stretching back through time all the way to the only successful slave revolution in recorded history and beyond. A summation and a celebration. It’s also just a freakin’ party, where all the significance of what Lakou means ends up in the bottom of a bottle of rum. With deep roots in the mountains of north Georgia, young Hedy West presented authenticity and authority in her singing of old time folk music. By the early 1960s she had become a mainstay of the growing traditional music revival in America, having written the often-covered “500 Miles” and dazzling audiences with

With deep roots in the mountains of north Georgia, young Hedy West presented authenticity and authority in her singing of old time folk music. By the early 1960s she had become a mainstay of the growing traditional music revival in America, having written the often-covered “500 Miles” and dazzling audiences with

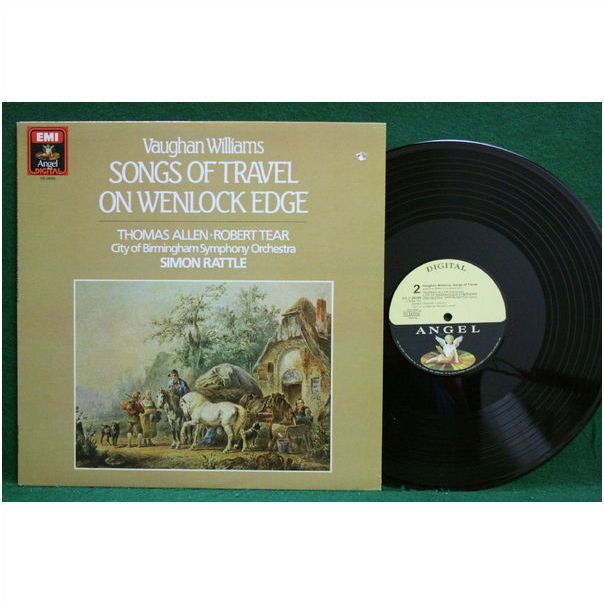

In 1977, the same year Jethro Tull recorded

In 1977, the same year Jethro Tull recorded  By 1977 Jethro Tull was beginning to wear out its welcome in punk-crazed Britain, but the band was still in its prime creative period. Since 1971’s Aqualung, Tull had been working toward a singular brand of progressive rock, fusing its blues and jazz leanings with the sound and presentation style of traditional songs to create, in the hands of Ian Anderson and his cracked, acerbic writing and vocalizing, an often wickedly pointed baroque folk songbag. Songs from the Wood gave full voice to Tull’s rural idylls, and provides a kind of bookend to what the

By 1977 Jethro Tull was beginning to wear out its welcome in punk-crazed Britain, but the band was still in its prime creative period. Since 1971’s Aqualung, Tull had been working toward a singular brand of progressive rock, fusing its blues and jazz leanings with the sound and presentation style of traditional songs to create, in the hands of Ian Anderson and his cracked, acerbic writing and vocalizing, an often wickedly pointed baroque folk songbag. Songs from the Wood gave full voice to Tull’s rural idylls, and provides a kind of bookend to what the  The traditional folk music community — the collectors and pedagogues in the first half of the 20th century who defined the boundaries of the vernacular music fueling the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s — probably had little use for a John Jacob Niles, scholar and singer of traditional and local songs whose work bore an imprint so unique that his interpretations took on a life of their own. Armed with giant lutes and dulcimers of his own devise, he would sing in a classically-trained impassioned vibrato whoop (Henry Miller described it as “ethereal chant which the angels carried aloft to the Glory seat”), investing in his songs a Kentuckian-by-way-of-France mondo spirit that channeled, intentionally or not — for Niles was a Modern — what Greil Marcus would later call the Old Weird America, inspiring a young

The traditional folk music community — the collectors and pedagogues in the first half of the 20th century who defined the boundaries of the vernacular music fueling the folk revival of the 1950s and 1960s — probably had little use for a John Jacob Niles, scholar and singer of traditional and local songs whose work bore an imprint so unique that his interpretations took on a life of their own. Armed with giant lutes and dulcimers of his own devise, he would sing in a classically-trained impassioned vibrato whoop (Henry Miller described it as “ethereal chant which the angels carried aloft to the Glory seat”), investing in his songs a Kentuckian-by-way-of-France mondo spirit that channeled, intentionally or not — for Niles was a Modern — what Greil Marcus would later call the Old Weird America, inspiring a young