Like Thelonious Monk, I like everything. But a little bit of everything — not everything of everything. Within about 30 seconds to a minute of hearing a track someone is “showing” me for the first time I decide whether I’ll invest time exploring the artist.

The other evening I was reading an article while my wife was listening on her phone to a band that had appeared earlier that day on the WDVX (Knoxville, TN) Blue Plate Special. Twelve seconds into “Deep Blue Eyes,” I heard what I figured to be the familiar affectation of a young contralto voice. “No. No, no. Not another hipster band.” Already, my mind was conjuring images of the group — bearded men with goofy hats and suspenders; she, probably wearing some 1920’s floral print with loud lipstick and hairstyle to match.

At 47 seconds, however, something unusual happened with the mandolin. It climbed the scale, ripping open an attic of dense harmonies. The driving instrumental break, pausing to get its breath before again lunging forward, signaled something beyond my first impression.

I don’t know

Which way we are being pulled

But the stars are sewn into the sky

To guide us on our way

And then, “Down, down, below the waves…” By the 2:20 mark I had minimized whatever forgotten article I was reading and was Googling, “…who is this, honey?” “A band called Honeysuckle.”

My sincerest apologies to Holly McGarry, Benjamin Burns, and Chris Bloniarz for my prejudice. I promise that when you guys come back down South we will be there in the front row to see you.

Catacombs (Oct ’17) is the latest release from this Boston-based trio. How did I miss them? Liking everything sometimes devolves into too much time around the fringes: not bluegrass but traditional bluegrass; not progressive music but proto-prog, etc. Traveling the gaps are artists that pull together everything you love with unexpected dash and capacity.

Honeysuckle play traditional folk instruments (guitar, banjo, mandolin) with a jazz rock intensity and chiseled focus. The wordless vocals of “Constellations” might put one in mind of Fleet Foxes; but the musicianship is so staid and majestic that it takes wing under its own power, without an updraft of reverb.

The title track features a fusionist breakdown, introduced by a riff reprised at the end of an atonal final chorus that swirls like angry hornets. “Watershed” has a complex cadence and vocal delivery that would be at home on Tull’s Stand Up. “Chipping Away the Paint” recapitulates and expands on the themes introduced in “Constellation” and “Catacombs,” with bits of “Deep Blue Eyes” linked by a psychedelic jam and — what’s this? — a throbbing electric guitar riff. A sign of things to come? [Update: the band informed us that it’s actually the mandolin with heavy pedal effects]

Okay, maybe the brief whistling on “Greenline” is just a tad hipstery. But for those who ramble on toward Proghalla this track, like the rest of Catacombs, points out an inviting, picturesque path under familiar and constant stars. One definitely worth exploring.

From Honeysuckle’s living room, the title track…

Like Robin Pecknold of

Like Robin Pecknold of  Where

Where  Successful Americana music hews a particularly demanding line. It’s a “post” genre, looking to blues and oldtime musics as a starting point rather than an end, as a shared story for the getting-on-with of the next chapter. To say the least, there’s a large margin for failure. The masters of the form, like

Successful Americana music hews a particularly demanding line. It’s a “post” genre, looking to blues and oldtime musics as a starting point rather than an end, as a shared story for the getting-on-with of the next chapter. To say the least, there’s a large margin for failure. The masters of the form, like  In 2014, Bruce Springsteen covered

In 2014, Bruce Springsteen covered  Joe Henry always tells it like it is. What this “it” is depends on his song or object of the moment, but if artistry is about honesty then here’s a man who can be a W. Eugene Smith one minute and a Romare Bearden the next. His is an Americana in context, wrought with a realism that has to, must, consider the world beyond the borders of his song. And yet his skill at creating a complexity of life within the three- or four-minute lengths typical of his work belies this, so that his portraits are breathtaking and you are standing next to him, watching and hearing him compose a complete picture.

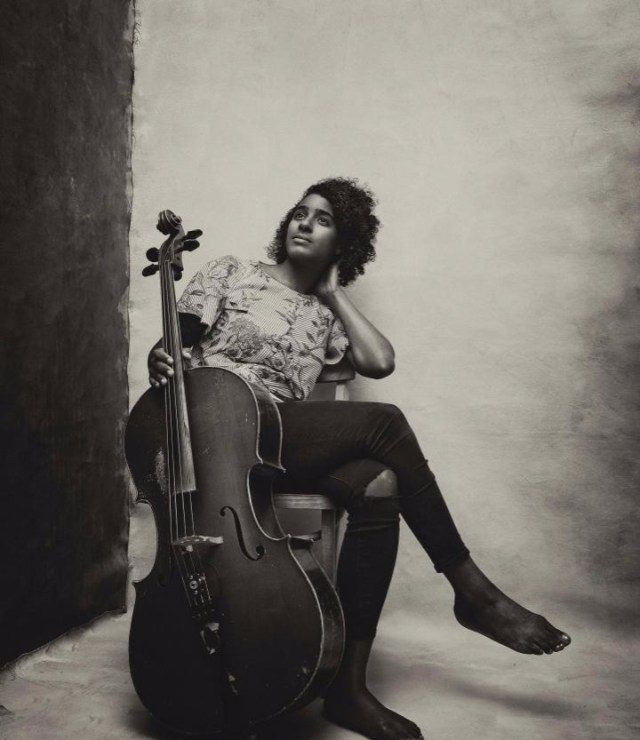

Joe Henry always tells it like it is. What this “it” is depends on his song or object of the moment, but if artistry is about honesty then here’s a man who can be a W. Eugene Smith one minute and a Romare Bearden the next. His is an Americana in context, wrought with a realism that has to, must, consider the world beyond the borders of his song. And yet his skill at creating a complexity of life within the three- or four-minute lengths typical of his work belies this, so that his portraits are breathtaking and you are standing next to him, watching and hearing him compose a complete picture. Free and blue and beautiful, those moorings Leyla McCalla holds to in her music sway and pitch like the gulf waters from Hispaniola to Lousiana, rolling through her cello and voice and coursing through her songs, lifeblood to an American music heart. In the weaving lines of the music she plays — a snaking, sliding creole so suited to, and perhaps partly a consequence of, the playing of fretless instruments — is the sound of an America taking shape as its many diasporas meet and mix and move, intersecting lines on a map that triangulate on New Orleans. Like the best Americana musicians, McCalla achieves something at once utterly contemporary but steeped in an authenticity of sound that says so much about the heart that makes the music. There’s no affected vocal, no hokum on the one hand or academic archness on the other. And there could have been, so easily. McCalla’s classically trained; she jumped from a New Jersey upbringing to a New Orleans residency; she’s an American born to Haitian rights activists in the thick of a struggle for democracy; she was an important member of the last incarnation of the much-loved Carolina Chocolate Drops. Her road was ripe for opportunity to leave the music behind in bringing a message that might not have resonated as strongly as it does. But instead she chose on her first solo record, Vari-Colored Songs (2014), to artfully adapt poetry by Langston Hughes and punctuate it with Haitian folk songs. Her second record, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, is also cloaked in a music-first approach that makes the underlying messages — because they are indeed there, as they were in her curation of Hughes’s work — so much more compelling.

Free and blue and beautiful, those moorings Leyla McCalla holds to in her music sway and pitch like the gulf waters from Hispaniola to Lousiana, rolling through her cello and voice and coursing through her songs, lifeblood to an American music heart. In the weaving lines of the music she plays — a snaking, sliding creole so suited to, and perhaps partly a consequence of, the playing of fretless instruments — is the sound of an America taking shape as its many diasporas meet and mix and move, intersecting lines on a map that triangulate on New Orleans. Like the best Americana musicians, McCalla achieves something at once utterly contemporary but steeped in an authenticity of sound that says so much about the heart that makes the music. There’s no affected vocal, no hokum on the one hand or academic archness on the other. And there could have been, so easily. McCalla’s classically trained; she jumped from a New Jersey upbringing to a New Orleans residency; she’s an American born to Haitian rights activists in the thick of a struggle for democracy; she was an important member of the last incarnation of the much-loved Carolina Chocolate Drops. Her road was ripe for opportunity to leave the music behind in bringing a message that might not have resonated as strongly as it does. But instead she chose on her first solo record, Vari-Colored Songs (2014), to artfully adapt poetry by Langston Hughes and punctuate it with Haitian folk songs. Her second record, A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey, is also cloaked in a music-first approach that makes the underlying messages — because they are indeed there, as they were in her curation of Hughes’s work — so much more compelling.