Unless otherwise noted, title links are typically to Bandcamp for streaming and purchasing, or to Spotify/YouTube for streaming with a additional purchase link following the review.

First off, the triple-disc elephant in the room: the Neal Morse Band’s An Evening of Innocence & Danger: Live in Hamburg. Morse, Eric Gillette, Bill Hubauer, Randy George and Mike Portnoy deliver exactly what the title says, plowing through the NMB’s most recent conceptual opus with the added excitement of rougher vocal edges and elongated opportunities for face-melting solos. Welcome deep cuts at the end of each set plus the heady mashup encore “The Great Similitude” heat things up nicely. The band’s delight in being back in front of a transatlantic audience comes through with (sorry not sorry) flying colors. Order from Radiant Records here.

Motorpsycho, on the other hand, cools things down on their new, palindromically titled Yay! This time around, Bent Sæther, Magnus “Snah” Ryan and Tomas Järmyr back off the booming drones, steering into light acoustic textures and Laurel Canyon vocal harmonies for a fresh, intimate variation on their spiraling neopsychedelia. Even with titles like “Cold & Bored” and “Dank State (Jan ’21)”, the results are inviting and exhilarating. (And don’t worry — the band’s penchant for the long jam is alive and well on more expansive tracks like “Hotel Daedelus” and closer “The Rapture”) My favorite from this crew since 2017’s The Tower.

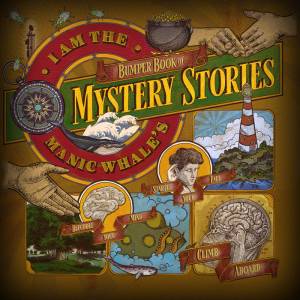

And, seconding Russell Clarke, I heartily recommend I Am the Manic Whale’s Bumper Book of Mystery Stories. Dialing down the snark of previous albums and turning up the atmospherics, it’s a thematically linked suite of veddy veddy British melodic prog vignettes engineered to thrill and disturb. Michael Whiteman and his jolly compatriots seem absolutely delighted to creep you out on “Ghost Train”, send your head spinning on “Erno’s Magic Cube”, and drag you into headlong adventure on land (“Secret Passage”), sea (“Nautilus”) and outer space (“We Interrupt This Broadcast . . .”). I felt like a kid again!

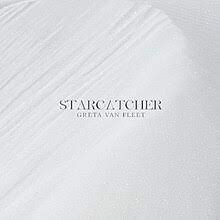

Meanwhile, Greta Van Fleet come slamming back with Starcatcher. With the polished studio sound of 2021’s The Battle of Garden’s Gate well and truly ditched, Frankenmuth, Michigan’s finest get down and dirty here, launching one ferocious rocker after another and mounting a stairway to . . . somewhere? on the trippy single “Meeting the Master.” Yeah, GVF still wear their influences on their capacious sleeves, and sometimes feel a bit inside the box for all the Kiszka brothers’ ecstatic caterwauling. But getting the Led out to Generation Z still strikes me as a worthwhile mission, and to see these young’uns keep the flame alight is all an aging rocker could ask for. Order from GVF’s webstore here.

Continue reading “Rick’s Quick Takes: Summer, Part Two”

Beginning in 1959, John Fahey’s “Blind Joe Death” excursions for solo acoustic guitar were the first to radically reconsider traditional blues and old-time music, extending by personalizing what Harry Smith did with the Anthology of American Folk Music (1952): rather than mythologizing what at that time was a largely unknown recorded legacy, as Smith did, Fahey made it breathe life, by quoting in his riffs on the traditional all manner of contemporary music. There is not a folk or jazz or avant-garde or prog rock guitarist who doesn’t owe Fahey a debt for this, for not only breaking boundaries — with which he was hyper-literate — but making such things seem irrelevant in the music he made.

Beginning in 1959, John Fahey’s “Blind Joe Death” excursions for solo acoustic guitar were the first to radically reconsider traditional blues and old-time music, extending by personalizing what Harry Smith did with the Anthology of American Folk Music (1952): rather than mythologizing what at that time was a largely unknown recorded legacy, as Smith did, Fahey made it breathe life, by quoting in his riffs on the traditional all manner of contemporary music. There is not a folk or jazz or avant-garde or prog rock guitarist who doesn’t owe Fahey a debt for this, for not only breaking boundaries — with which he was hyper-literate — but making such things seem irrelevant in the music he made. The art gallery of rock and roll is a rich and welcoming place, with room upon room spinning off into many-directioned distances. There is no entrance fee or warnings to stand back, please, from the piece. And, like at all great museums, any pretense to surface comportment is, if meaningful at all, only a nod of respect to the spark of human creativity. A sign that we don’t stand in willful ignorance. Before the work, within the work, we are all children. It is in rock’s nature to empower its listeners to create, and within this space there is no genre, no boogie no punk no progressive no pop no indie no folk, just an honoring of the empty canvas and the unrestrained fire banked down in humanity. It’s what I love about rock, and it’s what made Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks happen.

The art gallery of rock and roll is a rich and welcoming place, with room upon room spinning off into many-directioned distances. There is no entrance fee or warnings to stand back, please, from the piece. And, like at all great museums, any pretense to surface comportment is, if meaningful at all, only a nod of respect to the spark of human creativity. A sign that we don’t stand in willful ignorance. Before the work, within the work, we are all children. It is in rock’s nature to empower its listeners to create, and within this space there is no genre, no boogie no punk no progressive no pop no indie no folk, just an honoring of the empty canvas and the unrestrained fire banked down in humanity. It’s what I love about rock, and it’s what made Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks happen. The embrace of Arthurian legend and Tolkien-esque fantasy by British musicians in the 1960s and 70s — fueled undoubtedly by mixing the sounds of the folk revival with psychedelics and horrified revulsion at an overly industrialized and de-personalized world — worked to create some truly exotic hybrids in a scene that had also been profoundly influenced by American blues music and the sheer power of electric instrumentation. But whether it was Donovan or Led Zeppelin or Uriah Heep taking on the Roundtable and Middle Earth, there tended to hang over this music a hippie haze that could just as easily turn towards the naively dumb as the innovative. (Spinal Tap’s “Stonehenge” sequence is funny because it’s so spot-on, and as a Zep and Rainbow fan I laugh, and squirm, whenever I see it.) Leave it to Pentangle to get it right. As Bert Jansch introduces “Hunting Song” as a “13th-century rock and roll song” on this stellar performance from the band’s 1970 BBC special, his is a voice of wry authority. A key figure in the development of acoustic guitar playing in the 1960s, and a songwriter who found inspiration in the dark power of traditional music, Jansch was a musician who masterfully summed the denominators of blues and jazz and folk music early in his career, and until his death in 2011 was a guitarist’s guitar player. While Pentangle could not be said to be Jansch’s band, as it also included a cast of equals including guitarist John Renbourn, bassist Danny Thompson, drummer Terry Cox and vocalist Jacqui McShee, they built on the ground Jansch cleared in the mid 1960s along with

The embrace of Arthurian legend and Tolkien-esque fantasy by British musicians in the 1960s and 70s — fueled undoubtedly by mixing the sounds of the folk revival with psychedelics and horrified revulsion at an overly industrialized and de-personalized world — worked to create some truly exotic hybrids in a scene that had also been profoundly influenced by American blues music and the sheer power of electric instrumentation. But whether it was Donovan or Led Zeppelin or Uriah Heep taking on the Roundtable and Middle Earth, there tended to hang over this music a hippie haze that could just as easily turn towards the naively dumb as the innovative. (Spinal Tap’s “Stonehenge” sequence is funny because it’s so spot-on, and as a Zep and Rainbow fan I laugh, and squirm, whenever I see it.) Leave it to Pentangle to get it right. As Bert Jansch introduces “Hunting Song” as a “13th-century rock and roll song” on this stellar performance from the band’s 1970 BBC special, his is a voice of wry authority. A key figure in the development of acoustic guitar playing in the 1960s, and a songwriter who found inspiration in the dark power of traditional music, Jansch was a musician who masterfully summed the denominators of blues and jazz and folk music early in his career, and until his death in 2011 was a guitarist’s guitar player. While Pentangle could not be said to be Jansch’s band, as it also included a cast of equals including guitarist John Renbourn, bassist Danny Thompson, drummer Terry Cox and vocalist Jacqui McShee, they built on the ground Jansch cleared in the mid 1960s along with  One of the few individuals who could lay any real claim to being essential to the British folk revival, Elaine “Lal” Waterson lent her unique voice — absolutely beautiful and instantly recognizable — to the records she and her brother Mike and sister Norma made as The Watersons, defining the passion and respect necessary to performing traditional material while opening up the freedom and possibility such songs allowed. Although a tremendous songwriter in her own right, she wrote sparingly, and before her death in 1998 created only a handful of records. “Midnight Feast” is from 1996’s Once in a Blue Moon, a collaboration with her son, guitarist and producer Oliver Knight. It is an unusual record; Knight’s inventiveness as an electric guitarist gives the album a consistently full and yet uncluttered sound, supporting his mother’s poetry and voice, highlighting her artful, at times jazz-like, delivery. Indeed, in tone and mood there is nothing so much like this album as Abbey Lincoln’s 1959 landmark Abbey is Blue, in its grooves an acknowledgement of the fullness of life, with its travails and its joys. A profound wisdom at work, speaking of the deeper mysteries.

One of the few individuals who could lay any real claim to being essential to the British folk revival, Elaine “Lal” Waterson lent her unique voice — absolutely beautiful and instantly recognizable — to the records she and her brother Mike and sister Norma made as The Watersons, defining the passion and respect necessary to performing traditional material while opening up the freedom and possibility such songs allowed. Although a tremendous songwriter in her own right, she wrote sparingly, and before her death in 1998 created only a handful of records. “Midnight Feast” is from 1996’s Once in a Blue Moon, a collaboration with her son, guitarist and producer Oliver Knight. It is an unusual record; Knight’s inventiveness as an electric guitarist gives the album a consistently full and yet uncluttered sound, supporting his mother’s poetry and voice, highlighting her artful, at times jazz-like, delivery. Indeed, in tone and mood there is nothing so much like this album as Abbey Lincoln’s 1959 landmark Abbey is Blue, in its grooves an acknowledgement of the fullness of life, with its travails and its joys. A profound wisdom at work, speaking of the deeper mysteries. Across three years and three albums, Nick Drake produced singular, autumnal music that in its vision and genius defies era and genre. An extraordinary guitarist, lyricist, and gifted writer of melody, Drake was a lone wolf, debilitatingly shy, and thus his records were midwifed, by producer Joe Boyd — to this day Drake’s champion — and arranger Robert Kirby, along with various luminaries from the British folk rock/jazz scene. Richard Thompson, one of the players, estimates Drake probably sold only 5,000 albums in total when they first appeared, and it would take a VW ad a generation after his death to bring his music to a wider audience, but Nick Drake’s discography carries a timeless beauty, the light of late fall, and I hear in it the expressiveness — pain, humor, love — of Van Morrison and the soft, breathy sway of Joao Gilberto. “Northern Sky” from Bryter Layter is to my mind a perfect song of deep love and yearning, informed by the sensitive playing of John Cale, Dave Pegg, and Mike Kowalski. It wasn’t the breakthrough Drake expected (Island Records declined to release it as a single), and, perhaps disillusioned by his own overt attempt at and ultimate failure to make a commercial record, it’s believed to be one of the reasons he stripped down his sound for Pink Moon. And yet “Northern Sky’s” shimmering, jazz-inflected pronouncement, “I never felt magic crazy as this,” and its bell-like arrangement, is as fitting and whole a description of Nick Drake’s music as any I can imagine.

Across three years and three albums, Nick Drake produced singular, autumnal music that in its vision and genius defies era and genre. An extraordinary guitarist, lyricist, and gifted writer of melody, Drake was a lone wolf, debilitatingly shy, and thus his records were midwifed, by producer Joe Boyd — to this day Drake’s champion — and arranger Robert Kirby, along with various luminaries from the British folk rock/jazz scene. Richard Thompson, one of the players, estimates Drake probably sold only 5,000 albums in total when they first appeared, and it would take a VW ad a generation after his death to bring his music to a wider audience, but Nick Drake’s discography carries a timeless beauty, the light of late fall, and I hear in it the expressiveness — pain, humor, love — of Van Morrison and the soft, breathy sway of Joao Gilberto. “Northern Sky” from Bryter Layter is to my mind a perfect song of deep love and yearning, informed by the sensitive playing of John Cale, Dave Pegg, and Mike Kowalski. It wasn’t the breakthrough Drake expected (Island Records declined to release it as a single), and, perhaps disillusioned by his own overt attempt at and ultimate failure to make a commercial record, it’s believed to be one of the reasons he stripped down his sound for Pink Moon. And yet “Northern Sky’s” shimmering, jazz-inflected pronouncement, “I never felt magic crazy as this,” and its bell-like arrangement, is as fitting and whole a description of Nick Drake’s music as any I can imagine. I realized last week when I featured

I realized last week when I featured