by Rick Krueger

In August of 2016, my wife and I vacationed in Stratford, Ontario — one of our favorite places to visit, due to its internationally acclaimed theater festival and its lovely riverside parks. Picking up local classic rock stations as we crossed into Canada, I noticed lots of talk about The Tragically Hip’s upcoming concerts in London and Toronto.

I’d heard of The Hip, but never got into them — partially because I’d moved away from metro Detroit, where good Canadian bands could easily score airplay and well-attended shows. I was surprised at the amount of hubbub around this tour; it was only after we returned to the States that I learned the reason for the buzz.

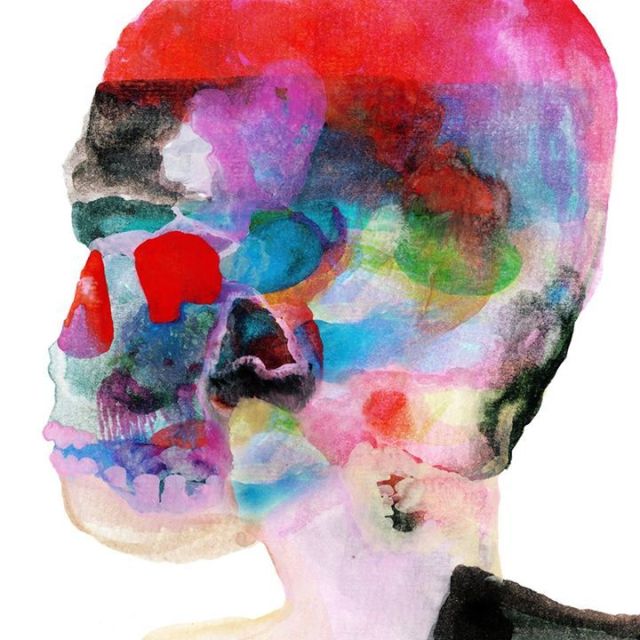

The Hip’s lead singer and lyricist, Gord Downie, had been diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, the worst kind of brain cancer, late in 2015. After finishing the 2016 album Man Machine Poem, the band decided on one last go-round of Canada’s hockey rinks, winding up in their Ontario hometown of Kingston in front of 6,700 fans in the local arena, thousands more on the surrounding streets, and a national audience on CBC.

Honestly, the music of The Tragically Hip is little more than well-executed, basic rock — lots of Rolling Stones and John Mellencamp grooves ranging from competently shambolic to tightly locked in. The secret sauce was Downie’s surreal, shamanistic lyrics. Stirring together a underdog outlook, the perspective of Canadians from the “great wide open” and random streams of consciousness (sometimes improvised live as the band rocked on — sperm whales were a recurring theme), they were fascinating precisely because they were sharp yet ambiguous, complex — even openly, defiantly confused. At their best (in my view, on the album Fully Completely and the compilation Yer Favourites) the group was pretty compelling.

Gord Downie passed away last night at the age of 53. To say he leaves behind a grateful nation is not an exaggeration. You can see and hear what Geddy Lee had to say about The Hip last year as the farewell tour wound down here, and read a well-wrought appreciation of Downie’s take on Canadian identity here. Banger Films (the folks responsible for the Rush documentary Beyond the Lighted Stage) have completed a film about The Hip’s final days, Long Time Running; it’ll be streamed on Netflix starting November 26. And check out the Yer Favourites compilation below. I especially recommend “Fiddler’s Green,” Fifty-Mission Cap,” “Courage (for Hugh MacLennan),” “Fireworks” — and if you only have time for one track, the fierce “At the Hundredth Meridian.”

“If I die of Vanity, promise me, promise me

That if they bury me some place I don’t want to be

That you’ll dig me up and transport me

Unceremoniously away from the swollen city breeze, garbage bag trees

Whispers of disease, and acts of enormity

And lower me slowly, sadly, and properly

Get Ry Cooder to sing my eulogy …”

Released in November 1968, the White Album did a Pollock on all the principles of freedom the Beatles had been shaping since 1965’s Rubber Soul kicked off their long, disciplined freakout, and splattered the canvas with every elementary Beatle colour: rock and roll, British music hall, folk-and-pop, country, novelty songs, in no apparent order or thematic unfolding. In its elemental, revelatory mess and as a rock double album it bears resemblance to

Released in November 1968, the White Album did a Pollock on all the principles of freedom the Beatles had been shaping since 1965’s Rubber Soul kicked off their long, disciplined freakout, and splattered the canvas with every elementary Beatle colour: rock and roll, British music hall, folk-and-pop, country, novelty songs, in no apparent order or thematic unfolding. In its elemental, revelatory mess and as a rock double album it bears resemblance to  The connections are clear, right? Michael Karoli’s cousin and girlfriend were the cover models for

The connections are clear, right? Michael Karoli’s cousin and girlfriend were the cover models for

In 2014, Bruce Springsteen covered

In 2014, Bruce Springsteen covered

Armageddon

Armageddon It’s not until it works its witnesses into a state of ecstatic frenzy, as if reading a preacher-inflected text so self-aware it reaches ascendancy, that New York rock satisfies itself and its audiences. It’s a city of distillations and self-regard, and so in its great contribution to rock and roll, New York puked up a revival so dazzling in its love for rock’s foundations it sometimes barely reads as the punk it became known as (or maybe a common idea of punk): there is no rejection, it is all embrace.

It’s not until it works its witnesses into a state of ecstatic frenzy, as if reading a preacher-inflected text so self-aware it reaches ascendancy, that New York rock satisfies itself and its audiences. It’s a city of distillations and self-regard, and so in its great contribution to rock and roll, New York puked up a revival so dazzling in its love for rock’s foundations it sometimes barely reads as the punk it became known as (or maybe a common idea of punk): there is no rejection, it is all embrace.