Successful Americana music hews a particularly demanding line. It’s a “post” genre, looking to blues and oldtime musics as a starting point rather than an end, as a shared story for the getting-on-with of the next chapter. To say the least, there’s a large margin for failure. The masters of the form, like Randy Newman and Joe Henry and Leyla McCalla, offer an unaffected, plain spoken drive to the heart of an America that is in its essence a crossroads. In such hands it goes far beyond a romance of sepia-tinged dustbowl-era hardscrabble, the sharecropper’s plow and his wife’s gingham print dress. It is the common song and in it is America.

Successful Americana music hews a particularly demanding line. It’s a “post” genre, looking to blues and oldtime musics as a starting point rather than an end, as a shared story for the getting-on-with of the next chapter. To say the least, there’s a large margin for failure. The masters of the form, like Randy Newman and Joe Henry and Leyla McCalla, offer an unaffected, plain spoken drive to the heart of an America that is in its essence a crossroads. In such hands it goes far beyond a romance of sepia-tinged dustbowl-era hardscrabble, the sharecropper’s plow and his wife’s gingham print dress. It is the common song and in it is America.

John Prine didn’t set out to do it, since as a genre it wasn’t really acknowledged until relatively recently, but he put flesh and bone to Americana songwriting. Equal parts humor, sadness, and frank talk as broad as its landscape, the pictures in his songs are drawn, I think, from the same kind of middle-of-the-country upbringing that so imprinted itself on Mark Twain. One of those songs, “Paradise,” from Prine’s 1971 debut, made its way to me as a tune John Denver covered on his 1972 album Rocky Mountain High. Which was the first album I ever owned, so that when I was six I knew that John Prine, credited on the sleeve, had written one of my favorite songs. Paradise was “where the air smelled like snakes, and we’d shoot with our pistols, but empty pop bottles was all we would kill.” How the air smells like snakes I don’t know but I know what he’s getting at somehow — it’s the kind of thing a guy from Missouri or Kentucky who grew up when Prine did would say.

“Angel from Montgomery” is Prine’s loveliest melody, but not necessarily as it’s sung by him. It’s been covered countless times, but it seems to be at its tuneful best if the singer is a woman, perhaps because its narrator is female. So Bonnie Raitt’s version is the go-to, and Susan Tedeschi is its current champion (following Raitt’s interpretation). But in these remarkable and wonderful tributes to Prine and his songwriting, what is absent is the charming gruffness Prine brings to the role play, and as recorded on that first record, an approach that is more gospel soul than sweet country ode. On an album absolutely loaded with outstanding songs, Prine goes with the piano and organ and the churchy atmospherics because this is a song about a tested faith, where things could’ve turned out differently, and would have, “if dreams were lightning, and thunder was desire.”

soundstreamsunday presents one song or live set by an artist each week, and in theory wants to be an infinite linear mix tape where the songs relate and progress as a whole. For the complete playlist, go here: soundstreamsunday archive and playlist, or check related articles by clicking on”soundstreamsunday” in the tags section.

Randy Newman makes diamonds. You can feel the pressure and time and heat that go into his songs, creating the effect of lush spaciousness in tunes typically clocking in under three minutes. His eagerness towards satire is a product of his style, immersive first-person character sketches delivering broad social commentary and comedy in lines simply phrased, acidic, and wrought with compassion. His skill at delivering his own songs is often eclipsed by his influence as a songwriter and his work as a hired gun — “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today” from his 1968 self-titled debut has been covered something like 75 times, and his scores and songs for films are in themselves a major achievement — and yet his unmistakable voice, coupled with arrangements measured to plumb the intellectual and emotional depths, carry such weight that as a performer of his own music he’s peerless.

Randy Newman makes diamonds. You can feel the pressure and time and heat that go into his songs, creating the effect of lush spaciousness in tunes typically clocking in under three minutes. His eagerness towards satire is a product of his style, immersive first-person character sketches delivering broad social commentary and comedy in lines simply phrased, acidic, and wrought with compassion. His skill at delivering his own songs is often eclipsed by his influence as a songwriter and his work as a hired gun — “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today” from his 1968 self-titled debut has been covered something like 75 times, and his scores and songs for films are in themselves a major achievement — and yet his unmistakable voice, coupled with arrangements measured to plumb the intellectual and emotional depths, carry such weight that as a performer of his own music he’s peerless. On Nebraska,

On Nebraska,  In 2014, Bruce Springsteen covered

In 2014, Bruce Springsteen covered  It’s not until it works its witnesses into a state of ecstatic frenzy, as if reading a preacher-inflected text so self-aware it reaches ascendancy, that New York rock satisfies itself and its audiences. It’s a city of distillations and self-regard, and so in its great contribution to rock and roll, New York puked up a revival so dazzling in its love for rock’s foundations it sometimes barely reads as the punk it became known as (or maybe a common idea of punk): there is no rejection, it is all embrace.

It’s not until it works its witnesses into a state of ecstatic frenzy, as if reading a preacher-inflected text so self-aware it reaches ascendancy, that New York rock satisfies itself and its audiences. It’s a city of distillations and self-regard, and so in its great contribution to rock and roll, New York puked up a revival so dazzling in its love for rock’s foundations it sometimes barely reads as the punk it became known as (or maybe a common idea of punk): there is no rejection, it is all embrace. Music critics tend to dismiss Joy Division’s posthumous Still as a hit-and-miss collection of studio scraps paired with a lackluster recording of their last show. And in a specific context — compared to the brilliant Unknown Pleasures and Closer, it seems a bit of a rush job with less-than-pure motivations — this holds some weight, although I’d argue as its own thing Still may be more representative of the band as a whole, and that the live half of the double album contains fiery performances wildly joining hard rock, punk, and synth-y goth music. My first exposure to Joy Division, over thirty years ago now, was hearing “Shadowplay” from Still, and it gave me the metal thunder frights. It sounded as if Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner, Ian Curtis, and Stephen Morris channeled the essence of Fleetwood Mac’s “Green Manalishi” through a punk filter, as they sped to the center of the city in the night. Even as they rode their wave of goth punk popularity their songs betrayed the band’s primary strength: their music was as much about making connections as alienation, masked and revealed in turns by Curtis’s not-waving-but-drowning lyrics and delivery.

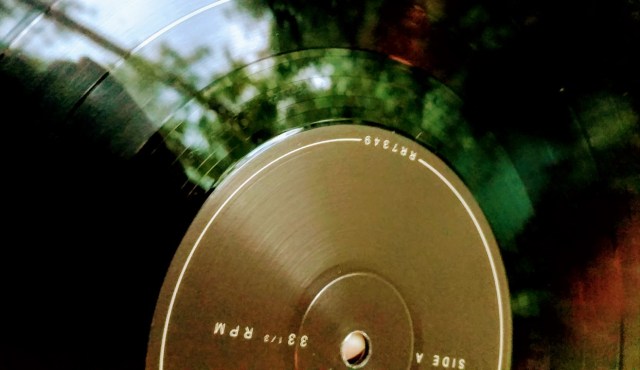

Music critics tend to dismiss Joy Division’s posthumous Still as a hit-and-miss collection of studio scraps paired with a lackluster recording of their last show. And in a specific context — compared to the brilliant Unknown Pleasures and Closer, it seems a bit of a rush job with less-than-pure motivations — this holds some weight, although I’d argue as its own thing Still may be more representative of the band as a whole, and that the live half of the double album contains fiery performances wildly joining hard rock, punk, and synth-y goth music. My first exposure to Joy Division, over thirty years ago now, was hearing “Shadowplay” from Still, and it gave me the metal thunder frights. It sounded as if Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner, Ian Curtis, and Stephen Morris channeled the essence of Fleetwood Mac’s “Green Manalishi” through a punk filter, as they sped to the center of the city in the night. Even as they rode their wave of goth punk popularity their songs betrayed the band’s primary strength: their music was as much about making connections as alienation, masked and revealed in turns by Curtis’s not-waving-but-drowning lyrics and delivery. Scored by S U R V I V E’s Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein, the Netflix show Stranger Things can at times seem written around the music, such is the importance of its soundtrack. The duo’s band creates very similar music but in longer form, developed stories in contrast to Stranger Things’ vignette accompaniments. If they recall the European progressive synth work of Jean Michel Jarre and Tangerine Dream, as instrumental narrative S U R V I V E’s tropes, fresh as they are, are the well-heeled scions of horror and suspense soundtracks of the 1970s and 80s — those coveted analog burblings so influencing rock archetypes that today a band like S U R V I V E can be embraced by a culture that may not have looked so warmly on the be-caped japes of synth lords in their keyboarded cathedrals of yore. This is a good thing, as is S U R V I V E’s 2016 album RR7349. The punky, catalog number-as-title approach is embedded in the band’s music, in its wordlessness plain spoken, symbolic of itself, its images so strong — or perhaps its ability to conjure notions and memories of images we’ve grown used to associating with such music — that there’s an enjoyable lack of heavy lifting here. As instrumental albums go, it’s a seamless ride through the horrorshow.

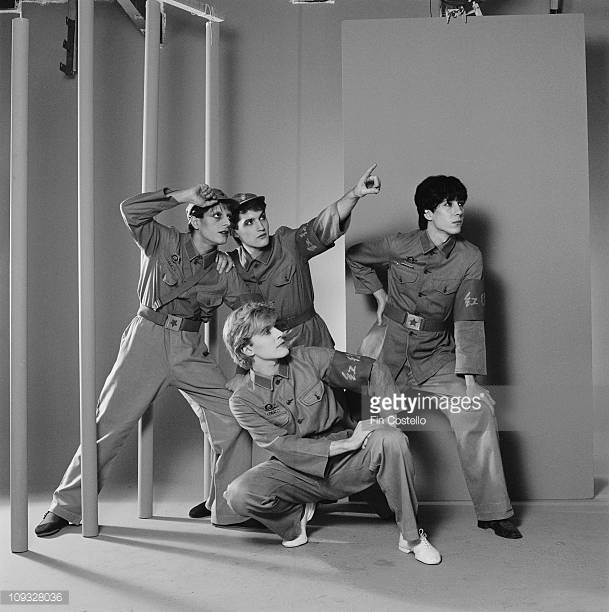

Scored by S U R V I V E’s Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein, the Netflix show Stranger Things can at times seem written around the music, such is the importance of its soundtrack. The duo’s band creates very similar music but in longer form, developed stories in contrast to Stranger Things’ vignette accompaniments. If they recall the European progressive synth work of Jean Michel Jarre and Tangerine Dream, as instrumental narrative S U R V I V E’s tropes, fresh as they are, are the well-heeled scions of horror and suspense soundtracks of the 1970s and 80s — those coveted analog burblings so influencing rock archetypes that today a band like S U R V I V E can be embraced by a culture that may not have looked so warmly on the be-caped japes of synth lords in their keyboarded cathedrals of yore. This is a good thing, as is S U R V I V E’s 2016 album RR7349. The punky, catalog number-as-title approach is embedded in the band’s music, in its wordlessness plain spoken, symbolic of itself, its images so strong — or perhaps its ability to conjure notions and memories of images we’ve grown used to associating with such music — that there’s an enjoyable lack of heavy lifting here. As instrumental albums go, it’s a seamless ride through the horrorshow. A British post-punk band could grow into just about anything in that fertile ground of the late seventies, and Japan proves the point, as over its short record-releasing career (1978-1981) the band moved from a funk punk glitz unit to new pioneers of progressive art rock. You can see the steam rising off the entire five-album catalogue, the creative engines driving full tilt, inevitably towards early breakdown. If the end came too soon there’s one more record, 1991’s self-titled Rain Tree Crow, that seals the deal: together, Mick Karn, Richard Barbieri, and brothers

A British post-punk band could grow into just about anything in that fertile ground of the late seventies, and Japan proves the point, as over its short record-releasing career (1978-1981) the band moved from a funk punk glitz unit to new pioneers of progressive art rock. You can see the steam rising off the entire five-album catalogue, the creative engines driving full tilt, inevitably towards early breakdown. If the end came too soon there’s one more record, 1991’s self-titled Rain Tree Crow, that seals the deal: together, Mick Karn, Richard Barbieri, and brothers  The figure “singing from the window in the Mission of the Sacred Heart” in

The figure “singing from the window in the Mission of the Sacred Heart” in